A girl’s skeleton in the museum: On runaways, the Jersey Shore and a cold case that haunted me

Once I got it in my head to go visit the girl skeleton at the Smithsonian, I couldn’t shake it. Her name was New Jersey Skeleton 1972, but everyone called her Sandy: forever 15, presented to the museum’s anthropology department by the police. A strange gift. I learned about her in a book published the year I was born, as I read up on teen runaways in the late ’60s and early ’70s, a group that included my own mother, for my memoir. My mom is the only grown-up teen runaway I know, but she was apparently a drop in a wave. New Jersey Skeleton 1972 was the phantom girl I was taught to fear becoming myself: the girl with the trusting smile, the girl with the grabbed wrist, the girl kept in the room, the girl dumped in a ditch.

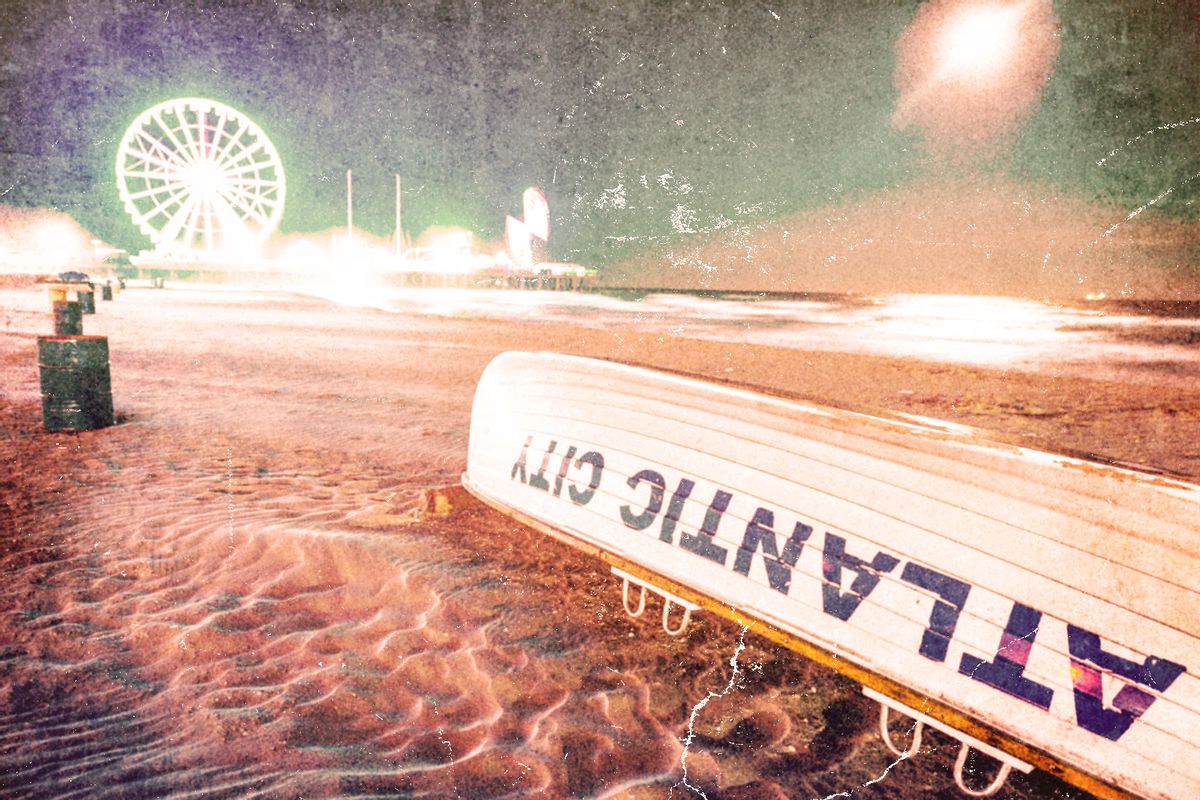

Sandy had been spotted hitchhiking near the Jersey Shore in the spring of 1971, around the same time my mother left home the second time, for good. Six months later, two hunters discovered Sandy’s body in a gravel pit on the side of US 30 near Egg Harbor, with nothing but a hotel key in the pocket of her flared denim trousers.

For six months, he told no one about the girl who had vanished.

There was a man. Isn’t there always? But he was cleared by the cops, deemed a good enough guy, though he was also old enough to book himself and Sandy into a motel and buy her the bell bottoms she had on when she died. In “America’s Runaways,” Christine Chapman reports what the man told the police: that she had said her name was Sandy, but he didn’t believe her; and that she was on her way to Atlantic City to get a summer job with no bag, no nothing. He took care of her, bought her clothes, fed her, got them a motel room, and spent the night there. He went off to work in the morning, and when he came back two days later, she was gone. “He seemed kind, and she needed a place to stay,” Chapman writes, though Sandy’s bones could not corroborate this account. After waiting for her at the motel for two days—without calling the police—the man checked out and “returned to his routine and forgot about Sandy until New Jersey police confronted him with the fact of her death.” For six months, he told no one about the girl who had vanished. Nobody tied a known missing person to the bones found in a roadside gravel pit. He seemed kind.

Six months after that, in 1972, the cops gave her body—a young and recent specimen, a rare prize for the anthropology department—to the Smithsonian, where they read her bones to see what story she might tell.

“Teenagers are an abstraction,” a Smithsonian anthropologist told Chapman. “Until you know one, as I know Sandy, they are not very real to you.”

But did she know Sandy? What could she know of her? Like Bruce Springsteen’s Sandy, the South Jersey girl he pleads with in his song “4th of July, Asbury Park,” she is a creation, a composite of every girl who took off from or toward something and ended up in a drawer, attached forever to some guy’s story that frames him as the hero, the one who tried to save her and lost something of himself in the process. Imagine being left with only that. Could Madame Marie read this Sandy’s fortune better than the cops could? What would she make of that man in the motel room? Of Sandy’s parents, who never claimed her? Of the Smithsonian, that temple of knowledge?

* * *

How could a missing girl go missing again, decades later?

I emailed the collection manager of archaeology and ethnology in the Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology to ask about Sandy. I wanted to see her. I couldn’t quite articulate why in a way that didn’t make me sound like a weirdo with a true crime podcast. Maybe I wanted to reassure her that someone remembered her, even if it was someone she had never met, someone who wasn’t even alive when she had died. Maybe it was to confront the end I grew up fearing the most. This collection manager couldn’t help me, but he referred me to one of the museum’s forensic anthropologists. He also couldn’t help, but he referred me to another anthropologist who had been at the museum when Sandy was admitted to the collection. That senior anthropologist had no recollection of this “specimen,” as he called her, and he referred me back to the forensic anthropologist. The emails were polite but dizzying. How could a missing girl go missing again, decades later? The first time was a tragedy. Losing her again was a farce.

At my persistent request, the forensic anthropologist took a closer look at the records and discovered that Sandy had been “deaccessioned” from the collection.

“These are restricted files, so I will have to go to the National Anthropological Archives to look at this file and see what documentation is in this file,” he told me. “If you want access to the file, you will have to get written permission (on letterhead) from the Atlantic Co. Medical Examiner’s office.”

When I looked for a contact there, I found yet another roadblock. The Atlantic County Medical Examiner’s office had vanished—along with, presumably, its letterhead—the casualty of a bureaucratic merger. Once again, Sandy lay in limbo, unclaimed. I tried to deaccession her from this story, to put her out of my mind, but I couldn’t.

* * *

I found the right form to submit to the consolidated New Jersey Southern Regional Medical Examiner’s Office, and I mailed my request for a letter of permission to view Sandy’s files in the National Anthropological Archive, which I acknowledged was “a little odd.” A medicolegal death investigator emailed me back. She couldn’t release any information about Sandy to me because the case of her death, while cold, was still open. She gave me what she could: a missing persons number to look up in the national database and an offer to have a staff anthropologist run DNA or dental records of any missing person I might suspect could be Sandy against her records.

“Stay safe,” she signed off.

I plugged Sandy’s number into the database. There she was, in more detail than I thought possible. She was small: 5’3″, 118 pounds. She dyed her hair, which was found in shades of blond, brown, and red brown. “Body discovered in woods off of Jim Leeds Road near milepost #42 of the Garden State Parkway in Galloway Township, New Jersey,” it read. “All parts recovered; not recognizable—near or complete skeleton.” She wore “a ribbed blue cotton or synthetic shirt”; “white, blue, and orange striped canvas or cotton trousers of the hip-hugger variety”; underwear and a white bra; and brown leather sandals—all found on her body. On her wrist, she wore a wide brown leather band inlaid with small brass grommets, a delicate ladies Westclock watch embedded in it—a perfect contradiction of girlish and rocker style.

And there was her face, or at least several artistic renderings of it, no two looking alike: a couple of scowling, crude police sketch composites from 1971 and ’72; one 3D computer model in which she looked a bit like Mariel Hemingway the year she filmed “Manhattan.” One girl can be so many girls all at once. There was also one more recent portrait: home-trimmed bangs framing her alert eyes, her mouth almost ready to smile at a man’s jokes.

I found myself feeling attached to Sandy, but I was just the latest person to fail her. I had no leads for the medicolegal death investigator’s cold case, no DNA for the anthropologist to cross-reference against hers. I had nothing to give this girl. I wanted someone to know—the clothing store clerk, the motel manager, the diner waitress, the man who had bought her those striped hip-huggers and then forgotten about her until the police came calling—that a girl doesn’t just vanish as if she never existed.

I found myself feeling attached to Sandy, but I was just the latest person to fail her.

Where was Sandy going when she met the man who bought her new clothes, fed her at a diner, and then took her back to a motel? When did she decide to name herself Sandy, leaving her given name behind? If she had a little sister, had that sister ever visited the Smithsonian on a school field trip, or later as a parent taking her own kids, without even knowing whose secrets the anthropology department contained?

I thought about what she had told the man, who seemed kind, about her plan to go to Atlantic City and find work. In Springsteen’s “Atlantic City,” which I love for its Catholic embrace of redemption through sacrifice and resurrection, the protagonist attempts to explain to his girl why he’s pinning his last hopes for the future on a desperate crime. The song is a mournful confession and, depending on how you hear it, possibly not entirely truthful. He has insurmountable debts, but he doesn’t mention how they have been incurred. Resentful and bitter over his lot, he is willing to gamble on this path, which he knows is a cheat, and bring her along with him into the aftermath. All he asks of her is that she fix herself up nice and be there waiting after he does a favor that presumably will lead to the squaring of his debts. We don’t know if the girl believed him or not, if she ripped up the ticket or pinned her hair up and put on her lipstick and went after her man. We don’t get to know how she felt when he failed to show up, as this doomed man almost certainly did, at their boardwalk meeting spot. The song is not her story. Sandy’s bones couldn’t tell me hers, either.

In high school, when I was just a year older than Sandy was when she died, I memorized all 206 bones in the human body. I learned how to name a skeleton part by part, from parietal to distal phalanx. It helped to carve the whole down into parts. I’d start with a small, manageable story: one hand has twenty-seven bones, split into three types—the carpals, the metacarpals, and the slippery phalanges. My practice skeleton was a body scribbled over, a story constantly revised and worn thin by eraser, a constellation of arrows surrounding each carpal by which she could be lured, dragged, pinned: trapezium, scaphoid, lunate, capitate. Rough jewels clustered like sea-tumbled shells, like gravel on a highway shoulder.

Read more

essays about complicated families: