Jemele Hill on Her Tumultuous Upbringing and the Tweet That Turned Her Life Upside Down

On September 11, 2017, Jemele Hill wrote a series of tweets that would change her life. In one, she called then President Donald Trump a “white supremacist” who “has largely surrounded himself w/ other white supremacists.” She went on to write that he was unqualified and unfit to be president, and that if he wasn’t white, he wouldn’t have been elected. “Those tweets were a culmination of a lot of things,” said Hill, five years later. “It got to a boiling point where I was tired of the excuses surrounding him.”

Hill was a seasoned sports writer and ESPN journalist and knew her words carried weight. Still, she wasn’t prepared for the intensity of the backlash, or the toll it would take on her mental health and career. Her tweets made both national and international news, with Trump’s press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders addressing them at a press briefing two days later, saying they were “one of the more outrageous comments that anyone could make” and a “fireable offense.” Trump himself tweeted about them, demanding the network apologize. “My situation was the final evidence for them that ESPN was a liberal organization that had gone unchecked,” Hill said. “I had basically handed them that argument on a tray.” She was handed a two-week suspension for violating the company’s social media rules less than a month later.

But news of her suspension once again compelled Trump to call her out personally. “He didn’t name me right away, but once I got suspended, he blamed me for the falling ratings at ESPN,” she told me in September via Zoom from her home in Los Angeles. “From there, came the escalation of hate mail and death threats to the point that the FBI was involved and I had to think about getting security. Folders full of hate mail called me every racial slur in the book. I was worried for my safety because the FBI had credible threats against my life.”

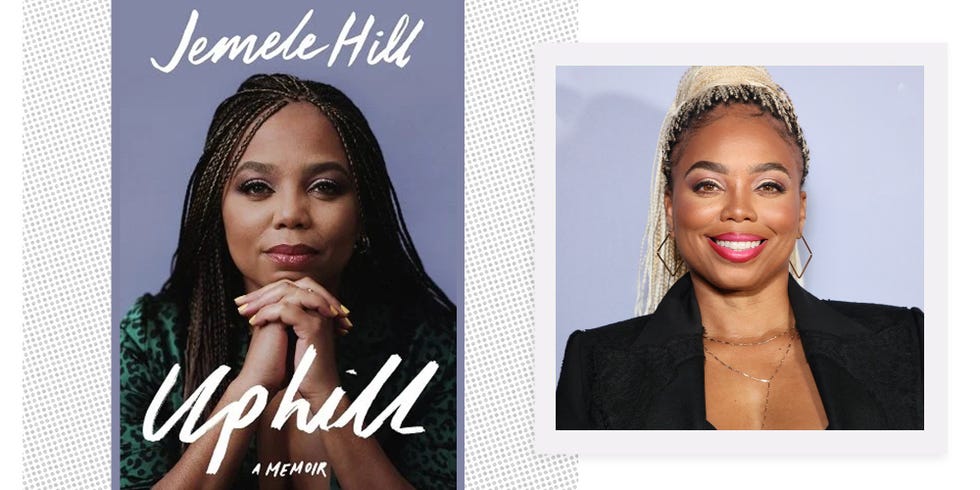

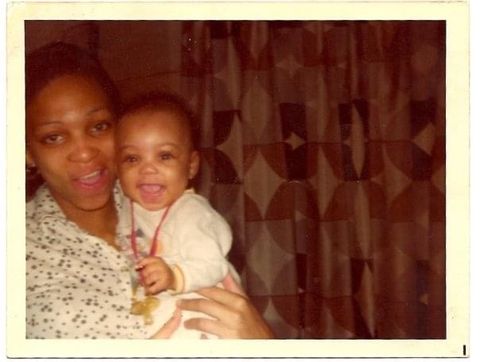

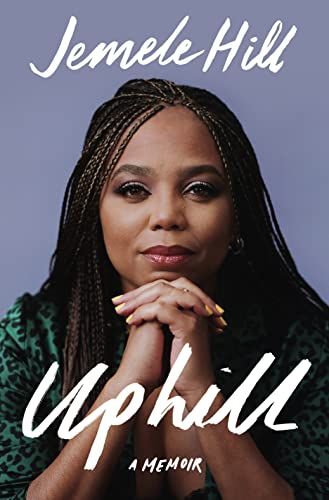

Hill recounts this difficult period in her life and much more in her memoir, Uphill, publishing Oct. 25. The book revisits her childhood and the trauma she experienced being raised by her mother, who was struggling with a heroin addiction at the time (her mother has now been clean for many years). “The scariest part for me was re-opening doors I felt I had closed,” said Hill, who now hosts the Spotify podcast Jemele Hill is Unbothered and is a contributing writer for The Atlantic. “I hadn’t thought about so many of the memories and I found that so much of the trauma was unaddressed. I also didn’t anticipate the extent of the pain. When I talked to my mother about it, I found out so many things that I didn’t know, and I had to be respectful so as not to make her relive the worst moments of her life.”

Hill’s love of sports journalism started with the man she calls her mother’s “sugar daddy.” When she was nine years old, her mother cleaned houses for an elderly widower in her Detroit hometown. “As a child, I had always naturally gravitated towards sports and had easy hand-eye coordination, but it was at [his] house where I became acquainted with newspapers and discovered that people actually had jobs where they wrote about sports,” she said.

While her mother worked, Hill would read the sports section of the Detroit papers and watch the Tigers games with her mother’s employer. “He gave [my mother] money, paid some of her bills, let her drive his car, all of which both directly and indirectly supported her drug habit,” she wrote in the book. Despite her young age, Hill was aware that there was more to his good nature. “I knew they were romantically involved and it disgusted me, but I felt more compassion for him than I did for some of the other men that enabled my mother’s heroin addiction.” The lasting positive impact of that time in her life is her enthusiasm for sports. “Out of trauma came something really great,” she told me. “And it stoked a love for what would become my lifelong passion.”

Her mother’s choices had a somewhat miraculous way of handing Hill opportunities that would have otherwise been out of reach. When she was in fifth grade, her second stepfather, William Dennard—a man with a good job, good credit, and health insurance (“my mother didn’t marry him for love and companionship,” Hill wrote)—enrolled Hill at the same private school as his son. “Pyramid Elementary wasn’t your typical private school,” Hill wrote. “It was Black-owned and the majority of the students and staff were Black.” Hill said she was able to learn at a high-level where Black culture was part of the core curriculum. Even though she was only there for fifth and sixth grade, Hill credits the school for opening her eyes to possibilities. “People talked a lot about going to college there and what life could look like outside of Detroit,” she said. “It made me feel like I could be unafraid to pursue adventures.”

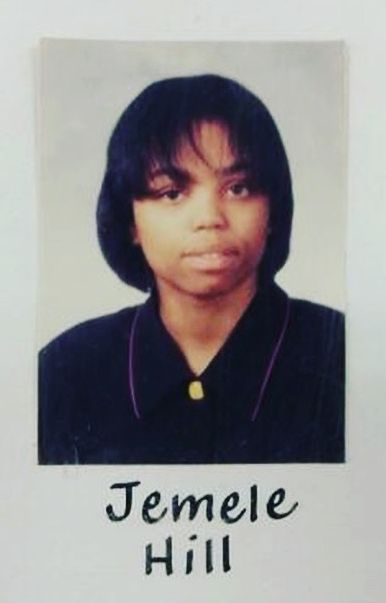

The summer before her junior year of high school, Hill attended a week-long journalism camp at Central Michigan University. She enjoyed it so much that she signed up for a journalism course at high school that year. She also started writing for the school newspaper, which led to a summer apprenticeship at The Detroit Free Press. While she was there, she attended a job fair at the annual convention of the National Association of Black Journalists. “Seeing all those Black faces at the convention left an imprint on my soul,” Hill wrote. “For the first time, I could clearly envision my future.” She went on to earn an academic scholarship to Michigan State University where she studied journalism.

At Michigan State, Hill started writing about sports for the college newspaper, but before long the opinion editor convinced her to start writing about politics and social issues as well, which unfortunately dealt her her first dose of hate. “It was the first time I wrote an opinion piece,” Hill said. “I was shocked that you could be called the N-word and threatened over something you wrote.” The campus police were called over the persistent hate letters she received, but over time, she became numb to the vitriol. “I hate to say it, but it was like, ‘Oh, here’s the latest one,’” Hill said. “I didn’t even have to be writing about race. I couldn’t understand how covering sports could compel people to threaten me this way.”

After graduating from college in 1997, Hill interned for a few months at The News & Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina, and then moved back to Detroit to work as a sportswriter for The Free Press, covering Michigan State’s football and basketball teams. It was around this time that she began to date a man named Larry. They brought out the worst in each other and Hill was about to break it off when she found out that she was pregnant. Larry came from a strict Christian household, but he supported Hill’s decision to get an abortion. “It was a conversation that we never had until we were faced with that monumental decision,” Hill said. She didn’t feel it was healthy to bring a child into the turbulent relationship. “I also didn’t want to be tied to him for the rest of my life,” she added. “The other part was my career. There were things I saw happening and I felt that this would interrupt that—and I wanted that more than I wanted this.”

In 2005, at the suggestion of a friend who worked for the Orlando Sentinel, Hill applied to be a sports columnist at the newspaper, even though she thought it was a long shot. But she got the job and worked at the paper for two years. Then, she landed at the last place she expected: ESPN. She was hired to be a writer, but her contract included 20 television appearances as well—an aspect that went against her image of what a respected journalist does. “It’s ironic that I was the kind of sports writer who didn’t want to work at ESPN,” she said, laughing. “SportsCenter was certainly a destination, but writers often don’t want to be on TV.” But money talks. “ESPN was offering a much higher salary and they were the dominant arm in the industry,” Hill explained “I would have been crazy to turn it down.”

Despite the culture shock of being on television, Hill discovered she was a natural. But as much as the producers booked her for shows, Hill felt that the higher-ups didn’t see her as more than a highly-qualified fill-in. “ESPN is an extremely competitive workplace,” she emphasized to me. “There is a constant fight for real estate—regardless of background.” Producers were partial to tried-and-true formulas. “What worked was what had already been successful,” Hill said. “They weren’t going to go out on a limb and try something different,” like giving a woman of color her own show.

In 2012, when her contract was coming up for renewal, Hill was ready for a change. She felt that she had done it all at ESPN and the inevitable next step should be a permanent TV job, but there was no such spot in sight at the network. So she decided to take an alternative approach to her dream by creating His & Hers, a sport statistics podcast with Michael Smith, then host of ESPN’s Numbers Never Lie. “We were a Black man and woman around the same age. There was no industry model where that would work. Even Black producers didn’t think we would work out as a permanent duo,” Hill said. But the duo’s chemistry coupled with thoughtful opinions was a hit and the podcast evolved into their own show of the same name. Six years of engaging chemistry paved the way for the two to co-anchor the evening edition of SportsCenter in early 2017. “It does give me a certain joy because after we were successful, there were more people putting together duos like ours,” Hill said.

The tweet about Trump put an abrupt halt to her career high. “Trump unlocked a lot of things about America that were already there. He didn’t invent white supremacy but he unleashed it in a different way. How he peddled it into our lives had a profound effect on me,” she told me. “When I sent out that tweet, I was at my wit’s end and I decided that Twitter was going to hear what had been roaming around in my mind for a long time. But being in the professional position I was in, it wasn’t something I should have spoken about publicly.”

In the five years since the fallout, the hatred has died down but Hill said she still feels aftershocks. “The last credible FBI threat was last year,” she said. “And I still won’t check my Facebook messages.”

Even though she still had two years left in her contract, Hill left ESPN in October 2018; in her book, she writes that she’d been mentally checked out since returning from her suspension.

Despite the upheaval of the past few years, Hill still thinks of her career as her safe haven. “It was a stabilizing force because I knew—for the most part—what to expect out of it. But I like to think of my husband as a stabilizing force too now,” she said of fellow Michigan State University graduate Ian Wallace, who she married in 2019. The same year, she launched her podcast Jemele Hill Is Unbothered, where she discusses politics, sports, and culture. Hill feels she is at a point where her life has come together. “It’s made all of those years of imbalance seem finally worth it.”

Wendy Kaur is a Toronto-based lifestyle, beauty and fashion writer whose work has been published in British Vogue, ELLE Canada, InStyle, FASHION, FLARE, and others.