Did the Supreme Court just become “political”? God, no — it’s always been that way

The Supreme Court is, and always has been, a political institution. That would be self-evident if not for the mystique that has been built up around America’s most important judicial body. That aura has started to dissipate — a recent Monmouth University poll found that more than half of Americans disapproved of the court’s recent performance — but it remains powerful enough that people take Chief Justice John Roberts seriously when he bemoans the supposed politicization of the Supreme Court. Before his retirement, Justice Stephen Breyer even published a book urging Americans to return the high court to its supposedly august and apolitical roots.

Now that the justices are evidently poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, those who insist (or imagine) that the Supreme Court must somehow remain above politics have become even more strident: Pro-choice advocates argue that the impending decision proves that that the high court has strayed from its constitutional mission, while the anti-abortion contingent insists that since judges are above politics their reasoning is unassailable — and the presumed leaker has immeasurably damaged the institution.

RELATED: The fall of Roe v. Wade will only embolden the fascists: How will America respond?

These arguments are almost stunning in their historical ignorance. For one thing, the framers of the Constitution basically said nothing about the Supreme Court’s mission, describing it simply as “one supreme Court.” The Judiciary Act of 1789, passed during the first year of George Washington’s presidency, fleshed out what the court would do, including assigning it six members (a chief justice and five associate justices; that number was officially expanded to nine in 1869). For more than a decade, however, the court took on few cases and had very little to do. The executive branch had proved strong under Washington and Congress quickly took on various legislative roles, but the judicial branch was initially unclear about exactly how much power it really had.

Chief Justice John Marshall understood something important: the appearance of putting partisanship aside would serve to legitimize more partisan decisions in the future.

Politics changed that. After John Adams lost to Thomas Jefferson in the 1800 presidential election, he decided to stack the judiciary with members of his Federalist Party so that Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans couldn’t implement their agenda. Yet some of the justices’ commissions were delivered prior to Jefferson’s inauguration, and since the new president believed that nullified their appointments, he instructed Secretary of State James Madison not to deliver them. One such appointee, Maryland businessman William Marbury, sued Madison, claiming that his appointment was legal and the government should be required to follow through with it.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Marbury likely believed that Chief Justice John Marshall, who was also a Federalist, would be sympathetic to his case; if so, he miscalculated Marshall’s ability to play the long game. Apparently more intent on increasing his own power than aiding his political party, Marshall authored the landmark 1803 decision which agreed with Marbury that Madison’s actions were contrary to law, but added that since the law involved was itself unconstitutional, it was not valid. So the precedent was established that the Supreme Court could strike down laws that it determined were in violation of the Constitution — which also launched the notion that the court was above politics.

Except it totally wasn’t. What Marshall understood was that the appearance of putting partisanship aside would help legitimize the court’s future decisions — even when they were blatantly partisan. (Arguably, the Roberts court’s ruling that preserved the Affordable Care Act, while disappointing many conservatives, played a similar function.) In Marshall’s case, this meant that the Federalist Party’s remained relevant long after the party of Washington and Adams had faded away. Future justices sought to preserve the mantle of legitimacy Marshall had bestowed, even when they used it for very different causes.

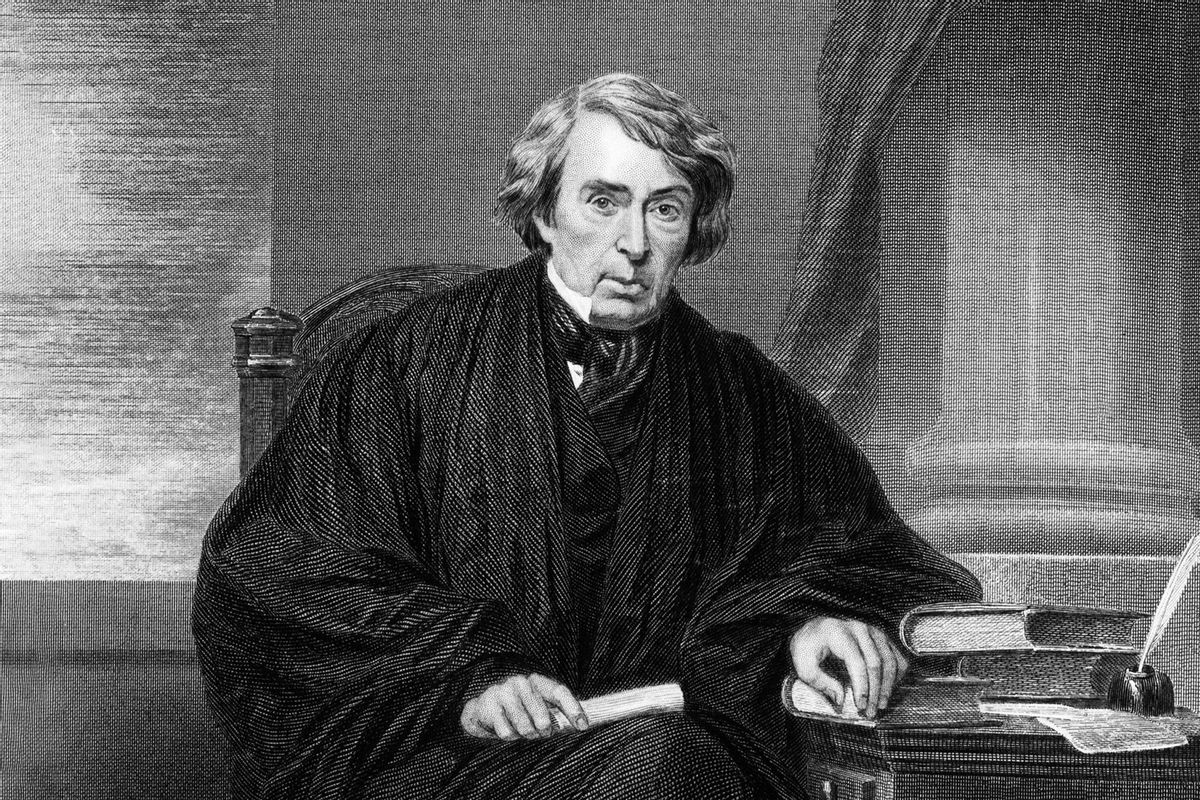

Consider the most infamous Supreme Court decisions of the 19th century: Dred Scott v. Sanford in 1857 and Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. In the first of those, the court ruled that an enslaved man in Missouri named Dred Scott could not claim to have been freed when his owners took him to Illinois and the Wisconsin territory, jurisdictions where slavery was illegal. In ruling against Scott, Chief Justice Roger Taney, an avowed white supremacist, found that people with African descent “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution,” and as such had no legal rights. (As Salon’s Keith Spencer recently noted, it is conceivable that people seeking abortions will face similar states’ rights issues after Roe is overturned.)

Going one step further, the court ruled that the Missouri Compromise — an 1820 legislative agreement that sought to limit the expansion of slavery in newly-added states or territories — was unconstitutional. Of course the justices claimed this decision was based purely on legal issues, but the historical consensus holds that it was politically motivated. Incoming President James Buchanan, who supported the Southern slave-owner aristocracy even though he was from Pennsylvania, exerted pressure on the court to side with the pro-slavery faction, and probably heard about the decision from Taney in advance.

After Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected, the politically-motivated tendency to “find” reasons why laws regulating business were unconstitutional went into overdrive.

Politics again trumped the law in Plessy v. Ferguson, which required the court to rule on whether Louisiana had violated the 14th Amendment by segregating railroad cars. Since the amendment held that whites and Black Americans were equal under the law, this created a logical conundrum. Yet the justices, clearly motivated by a desire to avoid alienating white supremacists, evaded that common-sense argument and found that accommodations could be “separate but equal.” The lone dissenter, John Marshall Harlan, called out the blatant political logic at play:

Everyone knows that the statute in question had its origin in the purpose not so much to exclude white persons from railroad cars occupied by blacks as to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons. Railroad corporations of Louisiana did not make discrimination among whites in the matter of accommodation for travelers. The thing to accomplish was, under the guise of giving equal accommodation for whites and blacks, to compel the latter to keep to themselves while traveling in railroad passenger coaches. No one would be so wanting in candor as to assert the contrary.

While those decisions upholding racial discrimination are the most obvious examples, politics has influenced numerous other Supreme Court decisions as well. While the Republican and Democratic parties have in many respects traded places as “liberal” or “conservative” formations since the 19th century, both have largely supported a social consensus favoring the interests of business over those of workers. It appears clear that when judges are appointed by politicians (in this case, nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate), their philosophies are likely to be shaped by politics. The Supreme Court has a long history of handing out decisions unfavorable to labor organizing or working people, even if they are presented in neutral-sounding legal language.

For instance, the 1899 decision Lochner v. New York overturned a law setting maximum working hours for bakers on the grounds that it violated the right to freedom of contract; that supposed right came up again in 1923, when the court overturned a minimum wage for women in Adkins v. Children’s Hospital. (That ruling, by the way, came under Chief Justice William Howard Taft, a former president. That’s the only time a former president has been on the Supreme Court, although Taft’s successor as Chief Justice, Charles Evans Hughes, was a former Republican presidential nominee.)

After Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected in 1932, the politically-motivated tendency to find reasons why laws regulating business operations were unconstitutional went into overdrive. There were four justices on the Supreme Court who clearly loathed FDR’s policies, and were determined to short-circuit his agenda however they could. Nicknamed “the Four Horsemen,” Justices Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland and Willis Van Devanter viewed themselves as ideological crusaders on a mission to take down a president they perceived as a dangerous socialist.

Roosevelt tried to solve the problem in 1937 through what is now called “court-packing” — specifically, by adding a new justice each time a current one passed the age of 70 but refused to retire. We’ll never know whether that might actually have made the Supreme Court less political, but in the event the plan blew up in Roosevelt’s face. His only consolation came in the form of an unexplained change of heart by Justice Owen Roberts, who had previously opposed the New Deal but voted to uphold Washington state’s minimum wage in the case West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish. That deflated Roosevelt’s court-packing plan — and solidified the entirely fictional notion that the high court was above politics, or at least was supposed to be.

Yet not much the court has done since Roosevelt’s era has made that notion more plausible than it was before 1937. In 2000, it installed George W. Bush as president in a 5-4 ruling that could not possibly have been more nakedly partisan. A decade later, in Citizens United v. FEC, the high court’s conservative justices managed both to side against Hillary Clinton and assert that corporate campaign expenditures were effectively political speech, and could not be regulated under the First Amendment.

More recently, of course, the Supreme Court confirmation process has become the focus of Machiavellian politics, largely because of Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, who refused to consider Barack Obama’s nominee in 2016, arguing that it was an election year, but pushed through Amy Coney Barrett’s 2020 nomination just days before Joe Biden was elected. Add to that the firestorm that surrounded Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation in 2018, and it’s almost bizarre that anyone can pretend the court is not infused with politics. Those three justices nominated by Donald Trump, of course, have created the conservative supermajority that has led to the near-certain downfall of Roe. That makes the court appear more political than ever before, perhaps — but appearance is not the same thing as historical reality.

Read more on the Supreme Court and the fall of Roe v. Wade: