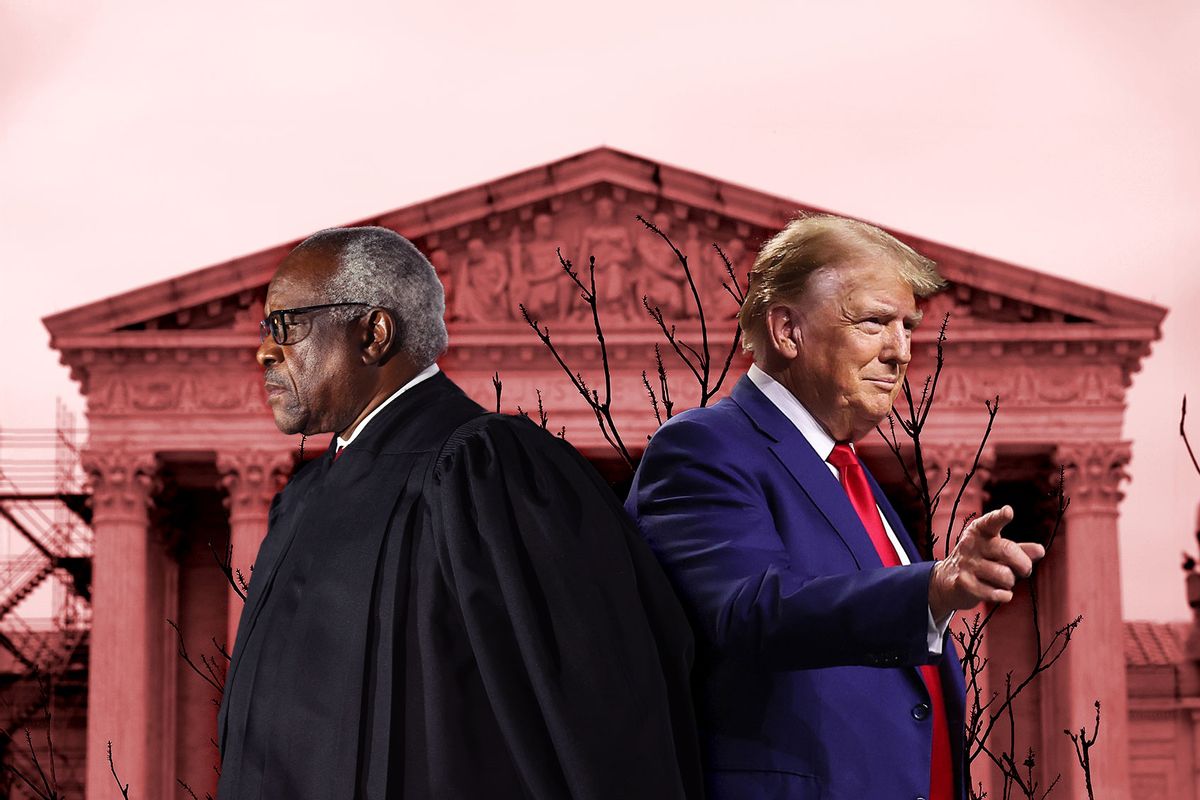

The Supreme Court, scrambling to save face, may delay Trump’s insurrection ruling

The Supreme Court’s credibility is at an all-time low. The last thing the court needs is the perception that it made a craven decision on the question of Donald Trump’s constitutional disqualification on the Colorado ballot for engaging in insurrection. But based on the oral arguments before the court Thursday, it looks like form will likely triumph over substance potentially doing the institution further injury.

The Trump disqualification case, Trump v. Anderson, could bury the court deeper in public esteem, especially if the court majority swallows some of Trump’s weakest arguments such as his claim that only “officers of the United States” are covered by the disqualification provision and that the president isn’t an officer of the United States. Unfortunately, at oral argument, Justice Neil Gorsuch and, surprisingly, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson seemed attracted by this claim.

They assume that the drafters decided to focus on excruciatingly fine distinctions in uses of the word “officers” while equally assuming that the drafters got busy doing other things and forgot to prevent a person who tried overthrowing our government from winding up running it from the most powerful post in the land—the presidency. Neither of these justices grappled with the absurdity of this assumption.

The impartial thing for the Supreme Court to do would be to uphold the Colorado disqualification ruling. But, if the court overturns it, it must do so without demolishing what’s left of the pedestal on which it once stood so high.

Likewise, the court will hurt its credibility if it swallows Trump’s “chaos and bedlam” argument. This was much discussed during the oral argument where fears of conflicting decisions among the states were raised, particularly by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito.

But this argument forgets that preventing chaos and bedlam is precisely the high court’s job. It has the final say over who is covered by the disqualification provision, how it is implemented, what constitutes an “insurrection” for purposes of the language, and what evidentiary standards courts should apply when adjudicating claims under it. Once it decides these issues, any decisions by states that don’t comply with it can be summarily reversed. If it’s the fact findings the court is worried about it can choose to independently review the facts of the Trump case and affirm or overrule the lower court findings—again creating a ruling the states must follow.

Justice Brett Kavanagh and Justice Amy Coney Barrett seemed to swallow another Trump red herring that only Congress can breathe life into the Fourteenth Amendment Section 3 language. But the language they rely on says Congress may pass legislation to enforce the provision. It does not say that Congress must pass legislation.

The language of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment is simple and requires no torment to interpret and apply: “[n]o person shall…hold any office…under the United States…who, having previously taken an oath…as an officer of the United States… shall have engaged in insurrection… against the same.” If the court chooses to ignore it on the grounds hotly debated at oral argument, the court majority risks more than just getting this case wrong.

The current court majority, particularly Justice Alito and Justice Gorsuch, support the legal doctrine of “textualism.” Put simply, textualists once claimed that judges should simply read the law and do what it says. If the justices use textualists arguments to refuse to see these simple words as a coherent whole, they will reveal that their textualism has morphed into pretextualism—little more than a smokescreen for imposing their own preferences. They will effectively proclaim that if a justice doesn’t like the implications of one set of words, they can simply pick a different set of words to obsess over until they are tortured into producing the result the justice wants.

With it impossible for the court to avoid losing face if it ignores the Constitution’s plain language, a credible delay might be its best hope. Two law professors pointed out in the Wall Street Journal that the 20th Amendment provides that, “if the President-elect shall have failed to qualify, then the Vice President-elect shall act as President until a President shall have qualified.” This suggests that the court should judge qualifications only after the election. If Trump loses, the problem goes away, but if he wins the court will face a heavy burden.

Still, the impartial thing for the court to do would be to uphold the Colorado disqualification ruling. But, if the court overturns it, it must do so without demolishing what’s left of the pedestal on which it once stood so high. Following oral argument, it’s not looking good.

Read more

about this topic