Even some left-leaning people support RFK Jr. — Here’s why conspiracy theories are so attractive

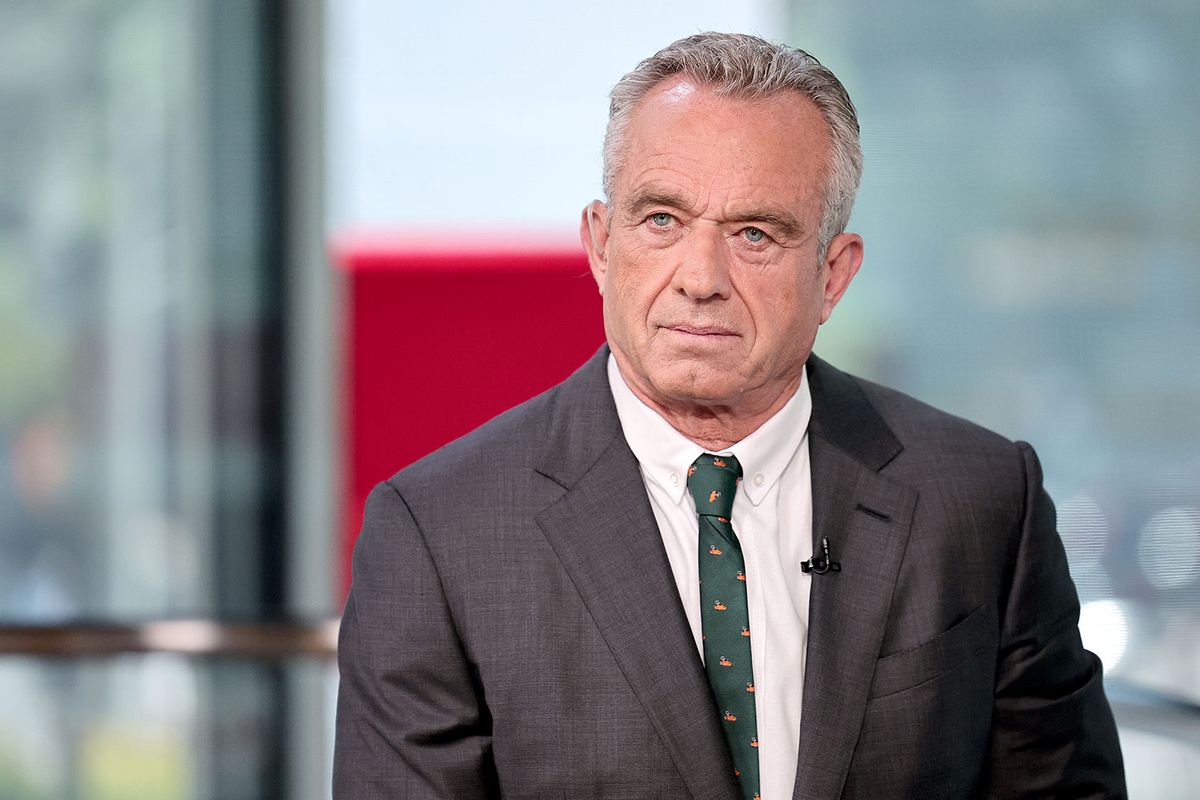

Last week, Joe Rogan hosted a three-hour podcast with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the anti-vaccine leader and conspiracy theorist who has declared himself a presidential candidate vying for the Democratic nomination.

As one would expect, the podcast’s content was brimming with dangerous soundbites of anti-vaccine misinformation, which have previously been debunked again and again, but are now recirculating amongst conspiracy theory circles. For example, Kennedy falsely implied that vaccines cause autism, which besides being insulting and stigmatizing toward people with autism, is not true.

Kennedy, the son of senator Robert F. Kennedy and nephew of president John F. Kennedy, also went on about how vaccines contain a dangerous form of mercury, touting his 2005 story “Deadly Immunity” that Salon and Rolling Stone simultaneously retracted in 2011, falsely claiming that childhood vaccines are poisoning children. (Thimerosal, a mercury-based preservative, is not dangerous and no longer used in most vaccines anyway.) In the podcast, Kennedy also claimed that Big Pharma suppressed data on COVID-19 and ivermectin, an off-label anti-parasite drug used for the treatment of some parasitic worms in people and animals.

On Monday, YouTube removed a video of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. speaking with Jordan Peterson for spreading anti-vaccine misinformation. Meanwhile, Spotify has done nothing. Kennedy shows no signs of staying quiet, so long as his content isn’t pulled down.

According to a 2021 report by the Center for Countering Digital Hate, there are 12 anti-vaxxers who are responsible for approximately two-thirds of the anti‑vaccine content that’s shared on social media platforms — including Kennedy. Now, as he kicks off his campaign, while clearly targeting podcasts as a favored medium, Kennedy has an opportunity to recirculate the dangerous misinformation he’s been spreading for years.

And as the misinformation spreads, it’s possible that more people will buy into it. Kennedy is reportedly pulling 20 percent support among Democratic primary voters, a figure which includes people like football player Aaron Rodgers and former Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey. As Media Matters recently reported, Kennedy’s anti-vaccine organization Children’s Health Defense has a history of partnering with right-leaning QAnon conspiracy theorists and organizations. Despite the connections to right-wing conspiracy theorists, why do some politically left-leaning individuals support Kennedy?

It turns out that believing in conspiracy theories doesn’t favor political lines. In a study published last year in Political Behavior, researchers analyzed the content of 52 specific conspiracy theories and found that neither democrats nor republicans were more prone than the other to engaging in conspiracy theories. “We found that both Democrats/liberals and Republicans/conservatives engage in motivated conspiracy endorsement at similar rates,” the researchers explained. Instead, there are other factors that contribute to the likelihood of people believing in conspiracy theories.

A conspiracy theory is usually a proposed plot suggesting that something was carried out in secret, usually by a powerful group of people. The end goal is positioned as a sinister one. As historians have pointed out, politics and history are no stranger to conspiracy theories — from reptiles ruling the world to fake moon landings to climate change being a hoax. However, several studies and researchers argue that Western democracies are in a “post-truth” era, and with the help of social media and uncensored media platforms, they’re more likely to become part of mainstream discussions and even be taken more seriously in presidential elections.

In general, researchers believe that endorsing a conspiracy theory is a form of “motivated reasoning.” In other words an attempt to make sense of something based on their own world view.

“Conspiracy theories tend to emerge when important things happen that people want to make sense of,” Karen Douglas, a professor of social psychology at the University of Kent in the U.K., previously told Live Science.”In particular, they tend to emerge in times of crisis when people feel worried and threatened. They grow and thrive under conditions of uncertainty.”

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

COVID, inflation, an upcoming presidential election, climate change, political uncertainty, student debt, an erosion of democracy — it’s no secret the U.S. is in a state of uncertainty, and everyone faces stressors on a daily basis. Douglas’ previous research also suggests that conspiracy theories can make people feel important and could provide a self-esteem boost to the believer.

“Perhaps conspiracy theories allow people to feel that they are in possession of rare, important information that other people do not have, making them feel special and thus boosting their self‐esteem,” Douglas wrote in the journal Political Psychology.

Rachel Bernstein, a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (LMFT) and host of the Indoctrination Podcast, who works with people in cult recovery, previously told me she believes the stresses of society contribute to conspiratorial thinking and can make people more prone to them — and that people who believe in conspiracy theories often exhibit “black and white” thinking. Berstein said they usually have “very little tolerance for things that operate in the gray, yet most things do” operate there.

“There is too much ambiguity and unpredictability, and it is tremendously uncomfortable and fraught with the unknown and things that only remain to be seen,” she said. “People who are more black or white thinkers search for absolutes and confirmation of their views.”

Berstein added that “much of the gravitational pull towards conspiracy theory is about the need to feel safe.”

One study published in the scientific journal PNAS suggested that improving basic social services could effectively decrease conspiratorial thinking in society.

“The evidence we presented suggests that the prevalence of rigid beliefs may perhaps best be mitigated by strengthening educational systems and addressing inequity and the related problems of poverty, conflict, food insecurity and social cleavage,”the authors state. “Put bluntly, measures such as a universal base income might go a surprisingly long way in reducing the resilience of harmful beliefs.”

In terms of the link between education and conspiratorial thinking, research published in Applied Cognitive Psychology suggests that people who believed in conspiracy theories could have less developed critical thinking skills. However, there are researchers who believe that loneliness could fuel conspiracy theories, too, as social exclusion could be linked to conspiratorial thinking. As researchers continue to figure out why people believe in conspiracy theories, the pressure will be on. From the “Big Lie” about the 2020 election to climate change denial, misinformation and “alternative facts” play an outsized role in our political landscape. As LA Times columnist Michael Hiltzika wrote recently, Kennedy is “emerging as a walking public health hazard.” The stakes are high given that conspiracy theories are a tangible threat to both public health and democracy.

Read more

about conspiracy theories