“Bama Rush”: The 7 biggest revelations from Max’s University of Alabama sorority rush documentary

There are a lot of things that go viral on TikTok, only to be left forgotten in a week, two weeks’ time. But not Bama Rush, the elaborate sorority recruitment process at the University of Alabama, tht arose as a cultural phenomenon thanks to its popularity on the app in 2021.

Regardless of what your “For You Page” on TikTok looked like, you probably came across a few videos of college-aged women documenting their journey to find the perfect sorority to be in — their new forever home. To many, the entire process may sound incredibly silly and frivolous. But in actuality, it’s extremely competitive and, at times, even soul-crushing.

When #BamaRush went viral on social media for the second year in a row in 2022, more people became invested in the elaborate antics, including film director Rachel Fleit. Fleit, who’s best known for the documentary “Introducing, Selma Blair,” attempts to showcase the entire process and cover its racist, complex history in her titled doc “Bama Rush.” Making the film, however, was not an easy feat for Fleit. Amid filming, Fleit received criticism, scorn and online threats from a controversial secret society that has ties to Bama’s frats and sororities.

The documentary itself follows four aspiring sorority pledges: Shelby, a high school senior from Quincy, Illinois; Isabelle, a high school senior from Rancho Cucamonga, California; Holliday, a Bama freshman from Orange Beach, Alabama, who’s looking to rush again after being blacklisted by her ex-sorority sisters; and Makalya, another Bama freshman from Leeds, Alabama. There are also interviews with Bama alumni, journalists and experts in the field of Greek life.

Here are the seven biggest revelations from “Bama Rush”:

Bama Rush (Photo courtesy of Max)

Bama Rush (Photo courtesy of Max)“Rush at the University of Alabama traditionally has kind of a bad rep,” said Trisha Addicks, a rush consultant. “It’s kind of a cutthroat process. It’s just uniquely Alabama.”

The entire process consists of four highly competitive rounds: Open House, Philanthropy, Sisterhood and Preferences. Sororities vote on their top potential new members (also known as PNMs) while PNMs vote on their preferred sororities in hopes of finding the perfect match. Multiple sorority sisters will first talk to one PNM before casting their votes on her. If the PNM gets high enough votes, she’ll be asked to return to talk to more sorority sisters.

Eventually, the PNMs will return to fewer and fewer sororities as they determine which sororities are the best fit for them. They also are judged on the basis of first impressions, conversation, values and academics. If the PNMs don’t meet a certain criteria, they will be dropped promptly.

After the final round, PNMs choose their top sororities and the sororities in turn choose their new members, or pledge class. It’s a dramatic and emotional affair that leads to bid day, when PNMs receive formal invitations from the sororities they’ve been invited to join. Afterward, PNMs run to their sorority to meet their new sisters.

Delta Kappa Epsilon Historic marker at the University Of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Alabama on July 5, 2018. (Raymond Boyd/Getty Images)

Delta Kappa Epsilon Historic marker at the University Of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Alabama on July 5, 2018. (Raymond Boyd/Getty Images)Greek life is a staple at Bama and has long influenced Greek life across university campuses nationwide. As for sororities, Alabama began admitting female students in 1893 and enacted its first sorority homes 12 years later. The oldest active sorority on campus is Kappa Delta, the Zeta chapter, which was formed in 1904. Coming in second is Alpha Delta Pi.

“I remember when we were going through recruitment at Georgia, we would all be looking at what Alabama was doing,” said Sloan Anderson, a rush consultant, in the documentary. “Yeah, they’re just the trendsetters. I think that’s why so many out of state decide to go to the University of Alabama and rush. It’s just this beast, because Greek life is everything at Alabama.”

Phi Gamma Delta Theta Chapter House at the University Of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Alabama on July 5, 2018. (Raymond Boyd/Getty Images)

Phi Gamma Delta Theta Chapter House at the University Of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Alabama on July 5, 2018. (Raymond Boyd/Getty Images)Bama sororities are deemed top, middle or bottom-tiered houses according to rankings from on-campus fraternities.

“I think a lot of the time people like to rank — and by people, I usually mean fraternity boys or boys in general,” said Anderson. “I feel like they’re like, ‘Oh, this house has the hottest girls, so they’re a top house. These freshman are the hottest freshmen, so they’re going to be considered a top house.'”

Anderson continued, “They have a social calendar, and they get to mix with certain sororities, but it’s only a limited amount. And the fraternities want to be mixing with the hottest sororities, of course, because they’re 20-year-old males. So that’s kind of where the ranking system comes from. They want to make sure the girls who are wearing their letters are up to their standards.”

Those in “top-tier” sororities also enjoy more benefits — be it academic or social — compared to those who are in lower-tiered homes. Rian Preston, an active member of Sigma Kappa, which is allegedly a “bottom-tier” sorority explained the perks in great detail:

“There are a lot of things that you’re entitled to when you’re in a top-tier sorority. You’re entitled to test banks that are going to help you on your exams. You’re entitled to people in your sorority that have better connections, whether their parents are richer or more connected. You’re entitled to a male gaze that might be a little more beneficial to you.”

Preston added, “So being in a ‘bottom-tier’ sorority, I have to understand that at some point, there’s nothing I can do to change institutionalized rankings.”

Isabelle and Sloan Anderson from “Bama Rush” (Photo courtesy of Max)

Isabelle and Sloan Anderson from “Bama Rush” (Photo courtesy of Max)Anderson explained that PNMs must refrain from discussing five topics, also known as “The Five B’s,” amid the recruitment process.

The first is “Boys,” namely fraternity boys. “If they bring it up, it’s OK to talk about it, just you don’t want to initiate that conversation,” Anderson advised Isabelle. The second is “Booze.” The third is “Bible,” meaning PNMs shouldn’t inquire about religion or ask what church the sisters go to. The fourth is “Bucks,” or money and wealth. And the final ‘B’ is “Biden,” which just means politics.

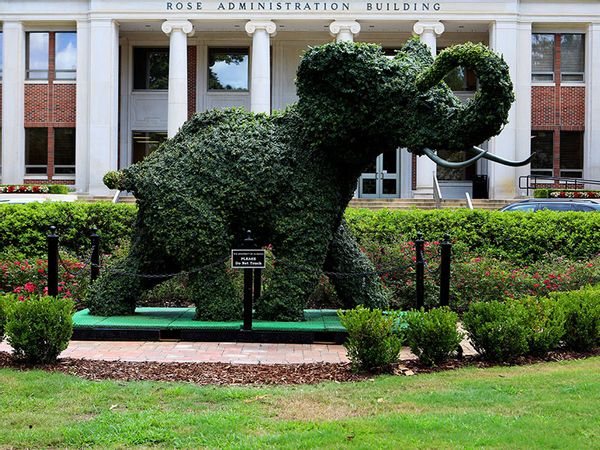

A sculpted Elephant, Alabama Crimson Tide’s mascot stands outside the Rose Administration Building at the University Of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Alabama on July 5, 2018. (Raymond Boyd/Getty Images)

A sculpted Elephant, Alabama Crimson Tide’s mascot stands outside the Rose Administration Building at the University Of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Alabama on July 5, 2018. (Raymond Boyd/Getty Images)Known as The Machine, the underground organization at the university consists of representatives from the school’s top sororities and fraternities who control everything from on-campus politics to the Student Government Association (SGA) and Homecoming elections. The Machine, a chapter of the national fraternity Theta Nu Epsilon, was founded in 1914 to decide on campus affairs in private. It is made up of 28 predominantly white fraternities and sororities who pay at least $850 per semester to fund the organization, per a 2011 report by UA’s student-run newspaper The Crimson White.

“The Machine systematically made sure that a minority group on campus of elite people who got special treatment, lived in special homes, who came from the most affluent and powerful families got an advantage on everyone else,” said John Archibald, a journalist and Bama alum. “It’s a way better teacher of how to do nefarious things for power than you could ever get in a political science class.”

“And I think it’s a threat to people’s hopes and dreams that they may not be able to fit into the crowd and maybe the tax bracket they want to fit into,” Archibald added. “I think the danger is not belonging — it’s not being one of the chosen people.”

When asked about The Machine, students were reluctant to talk about the organization and instead said, “We shouldn’t talk about that.” Considering how much power The Machine holds over Bama’s student population, it’s understandable why many current Greek life participants avoid discussing the infamous society.

Alex Smith, a Phi Mu alum and former Machine student senator, said that “something just felt really dark and ugly about” The Machine. Smith later penned an essay for The Crimson White titled “Why I’m leaving the Machine,” in which she exposed what the organization did behind closed doors.

Prior to the release of “Bama Rush,” online critics alleged that The Machine was coming for Fleit, HBO and all the participants in her doc. Fleit clarified that they were all rumors.

Women chatting outdoors (Getty Images/Maria Taglienti-Molinari)

Women chatting outdoors (Getty Images/Maria Taglienti-Molinari)The documentary delves into Bama’s tense past between UA Panhellenic sororities and Black students. In 1986, the Theta Sigma chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha, a Black sorority part of the “Divine Nine,” had a cross burned in the yard of their sorority house. The incident fueled a bitter racial divide within Bama’s Greek life — which persisted till 2013, when Alabama ended segregated sororities.

″It was a threat. It was a way of saying, ‘Black people can clean our houses, but they can’t move in next door,‴ said Reginald McCall, the then president of the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC), in a 1986 Associated Press report.

Bama alum and former homecoming queen Deidra Chestang Lane, who was a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, recalled the incident, saying, “We were terrified, and anger crept in later after we got beyond the shock and dismay of the entire situation.”

She continued, “I grew up in Alabama, so hearing that crosses were being burned is something that I grew up hearing about, but I’d never personally seen a cross being burned, and once you see that, you can’t unsee it. And it sticks with you for a lifetime.”

Makalya also explained that race remains a touchy subject amongst Bama students today: “Everyone here thinks I’m everything but Black. Like I’m white and Black. They think I’m everything.”

“If I’m too white, I’m whitewashed, but if I act too Black, then I’m not white enough,” she said. “Like, what am I supposed to be because I’m both races? Why can’t I just act myself? I’m not acting a race — you can’t act a race.”

Money flying off stack of bills (Getty Images/PM Images)

Money flying off stack of bills (Getty Images/PM Images)In addition to having their own rush consultants, PNMs are expected to drop between $4,170.03 to $4,978 in new member fees per semester. The hefty cost includes a chapter meal plan, local chapter fees along with one-time fees for pledging and initiation.

The documentary also notes that the average annual cost for new members of a sorority at Alabama is $8,300. Living in-house fees per semester range from $7,465.17 to $9,445, per The Birmingham News. Living out-of-house fees per semester range from $3,621.52 to $4,575.

Whether it’s societal pressures or financial pressures, the rushing process is daunting to many at Bama. So much so that some PNMs will drop out of the process halfway through rush week. At the end of the documentary, it’s revealed that Shelby gets into Phi Mu, a widely considered top-tier house. Isabelle gets into her first choice sorority, Alpha Delta Pi. Both Holliday and Makalya decide to not rush.

“Bama Rush” is currently available for streaming on Max. Watch a trailer for it below, via YouTube:

Read more

about Greek life: