Abraham Lincoln, master inventor: The true story of the only president to ever patent an invention

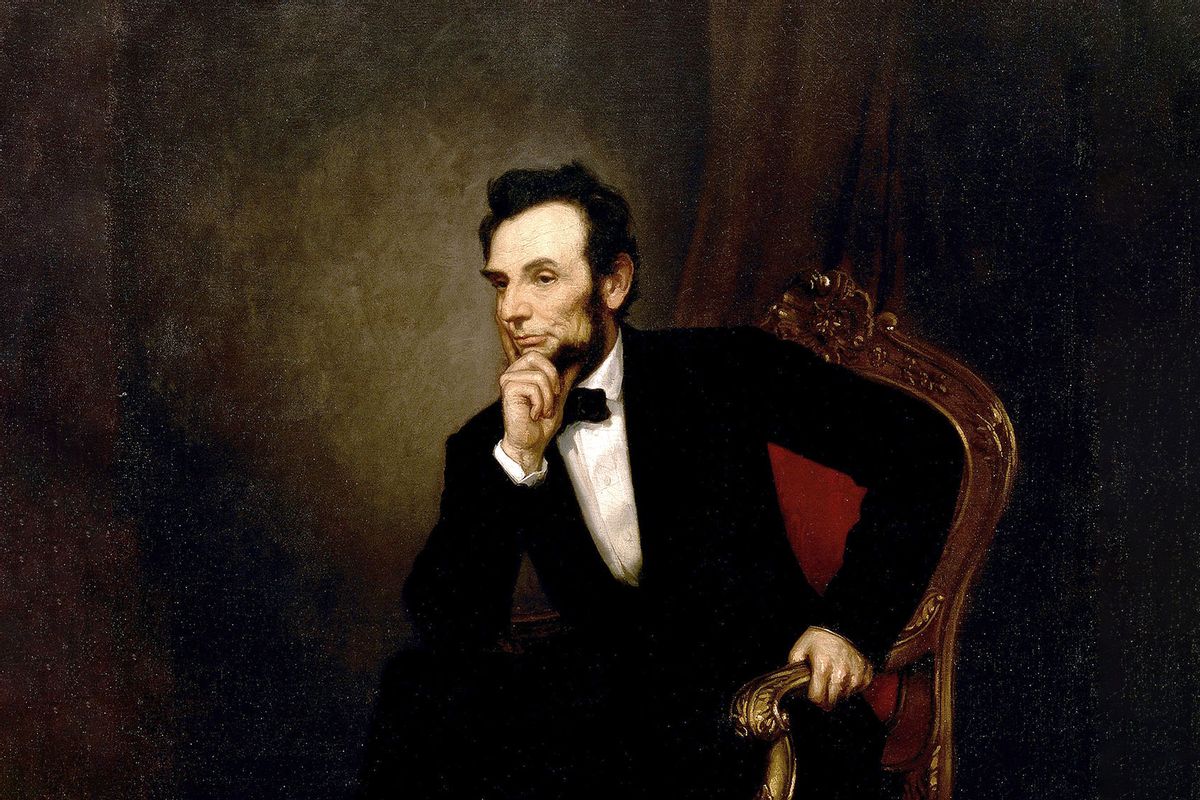

When you think of Abraham Lincoln, your mind probably conjures up an image of a tall, lanky man with a chinstrap beard and a stovepipe hat. Perhaps you also think of the 16th president’s most famous accomplishments — winning the Civil War and freeing the slaves — or of his early life, much of which was spent reading and writing even when his family wanted him engaged in physical labor. Like many daydreaming youths throughout history, Lincoln yearned to do great things with his mind, even though his peers insisted that he pursue work through his hands.

This, no doubt, explains why he is the only American president to patent an invention.

On May 22, 1849, only three months after the native Kentuckian celebrated his 40th birthday, the United States Patent Office issued Patent No. 6,469 for a device “buoying vessels over shoals.” The impetus for this invention was Lincoln’s own hard experience; as a ferryman navigating boats along the Sangamon and Mississippi Rivers, he had repeatedly been frustrated when his flatboat would get stranded and take on water. On one occasion, while he and several other men were trying to get to New Orleans, their flatboat became stranded on a milldam (a dam built on a stream to raise the water level for a water mill) near the small pioneer settlement of New Salem.

Having your flatboat regularly get stuck would be the equivalent today of facing massive traffic jams, or having your car constantly stall out.

As the boat took on water, Lincoln rose to the challenge. To right the boat, he dropped part of their cargo, then purchased an auger so he could drill a hole in the vessel’s bow and let out the water. Once that had been accomplished, Lincoln plugged the hole and then worked with the rest of the crew to move the boat over the dam. They succeeded, and soon he was back on his way to New Orleans.

Although Lincoln rarely shared this anecdote with people he met later in his life, it obviously stuck with him at the time it happened. In the mid-19th century Mississippi River Valley, rivers were the equivalent of roads and highways today; people needed them to easily transport themselves. Having your flatboat regularly get stuck would be the equivalent today of facing massive traffic jams or having your car constantly stall out. In other words, it was a big problem — and Lincoln clearly thought he could solve it.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Hence his invention. Lincoln’s idea was to place “adjustable buoyant air chambers” on the sides of any boat that would be traversing a river. Obviously inspired by the financial loss he had suffered by dumping part of his cargo on the last occasion when he had been stranded, Lincoln’s patent specifically mentioned that it would enable vessels to reduce their water intake and pass over bars or shallow water “without discharging their cargoes.” That is because the invention, once lowered into the water, could in theory be inflated to simply lift a boat over the various obstructions.

At least, that was Lincoln’s invention intention. To the best of our knowledge, his device was never sold or used by anyone, with Lincoln’s former law partner and biographer William Herndon dismissing it as “a perfect failure.” Yet in a 2018 article for the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, industrial designer Ian De Silva conducted a number of experiments to see if Lincoln’s invention could have worked. It didn’t — but not because the future president got the science wrong.

“On the contrary, it was a prescient concept and one that was scientifically tenable,” de Silva wrote. “Where Lincoln erred was in the execution, specifically his complicated system of poles and ropes that made it an invidious contraption. Had he devised a simpler and less intrusive means of inflating his bellows, the Great Emancipator might have also been remembered for an emancipation of a different sort — freeing boats captured by river sand.”

“…it was a prescient concept and one that was scientifically tenable,” de Silva wrote. “Where Lincoln erred was in the execution…”

David J. Kent, President, president of Lincoln Group of DC and author of the new book “The Fire of Genius: How Abraham Lincoln’s Commitment to Science and Technology Helped Modernize America,” told Salon by email that he too believed that Lincoln’s invention likely would have worked in practice if not for the cumbersome “system of ropes and poles and pulleys.” He also pointed out that Lincoln’s inability to make money off of the invention had less to do with his engineering aptitude than with more mundane realities.

“It is common for patents to meet the standards for being accepted but not ever be commercialized,” Kent pointed out. “Lincoln made no attempt to commercialize his design. He was too busy running a law firm and dealing with big picture political issues.”

At the same time, the invention is more notable for what it tells future historians about Lincoln’s character — and here, we must return to the young boy who found farm life to be dull and yearned to indulge his natural intellectual interests.

“For Lincoln, this was about observing a technical problem and his natural curiosity about how to resolve it,” Kent explained. “He never planned to try to make money off of it; solving the problem was his goal. He hated the subsistence farm life he was born into and was intellectually curious. He always sought to ‘better his condition.’ He did so through self-study, augmenting his meager formal schooling (less than a year total) with many hours of reading, writing, and turning over problems in his head until he felt he fully understood them.”

One can also glean something about Lincoln’s political philosophy through his invention. In his mind, scientific innovation and infrastructure improvement were moral imperatives as well as subjects of personal interest.

“Lincoln was a big believer in what we call infrastructure as the key to economic development and general prosperity,” Columbia University historian Eric Foner, author of “Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War,” told Salon by email. “His invention was connected with his support for making the Sangamon River more navigable, to spur the development of New Haven.” Although the development of American railroads changed transportation in America, Lincoln “gave a speech quite a few times in the 1850s on the history of inventions.” He strongly believed in the value of knowledge, and how it could be used for the betterment of mankind.

“For Lincoln, this was about observing a technical problem and his natural curiosity about how to resolve it,” Kent explained.

Harold Holzer, also a renowned scholar on Lincoln’s life and times, told Salon last year that Lincoln’s former political affiliation as a member of the Whig Party further explains his passion for infrastructure. Lincoln had “always passionately believed in infrastructure, including government investment in railroads, canals, and roads,” just like Whig Party leader Henry Clay, and as president this led him to push for major projects like the building of a transcontinental railroad.

Tellingly, Lincoln’s support for investments in science and technology put him on the wrong side of the racists of his time.

“In general, the slaveholding states rejected science and technology,” Kent wrote to Salon. “They, as many do today, said this was because they thought it would give too much power to the federal government. In reality, it was because they feared that it would loosen their power over both enslaved African Americans and poor white farmers in the South.”

By contrast, “Lincoln saw science and technology (and education) as a way to improve democracy by ensuring all of its citizens could ‘better their condition.’ This conflict between those who see America as a broad democracy where all of us have an equal chance and those who see America best served by a class of powerful leaders overseeing the masses has defined our history and continues to this day.”

Read more

about Lincoln