Elizabeth Acevedo’s Inheritance is a Searing Indictment of Colonized Beauty Standards

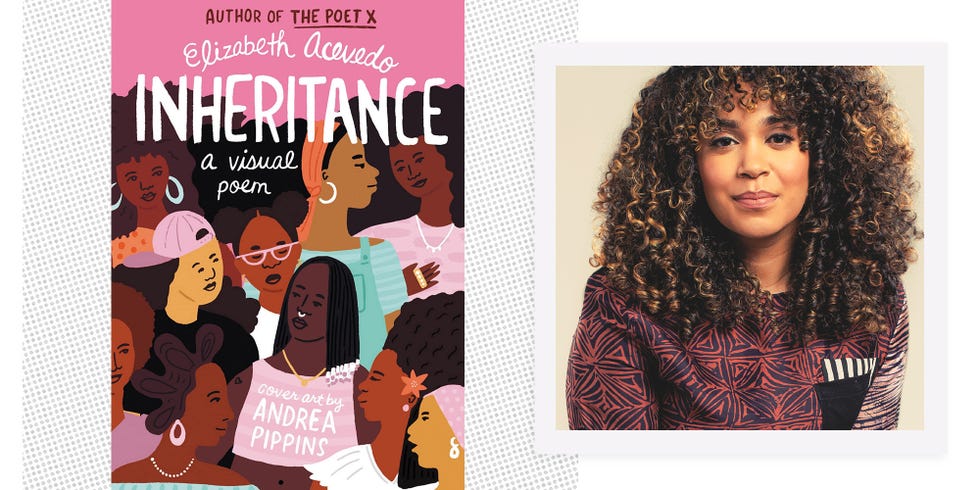

If there’s a writer I’d never hesitate to call a powerhouse, it is Elizabeth Acevedo. She is the New York Times bestselling author of three novels, most recently, Clap When You Land, a National Book Award winner for The Poet X, and the first writer of color to win the UK Carnegie Medal. But Acevedo’s star quality is greater than the sum of her accolades. A magnetic performer and storyteller, Acevedo writes for young people and adults, in verse and prose, about family, identity, and the dreams that women have for themselves. In work and in person, she speaks with piercing clarity and emotional realness. You never get the sense that Acevedo is playing you—she’s singing you the truth.

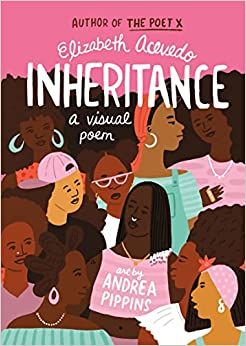

Acevedo’s latest book, Inheritance, is a visual poem about the complexities of Black hair from the perspective of a first-generation Dominican American. Featuring Acevedo’s words and vibrant, original art by Andrea Pippins, Inheritance is both intimate and historical, a searing indictment of anti-Blackness and colonized beauty standards, and an ode to self-love.

As a fellow Dominican writer, I’ve been a longtime admirer of Acevedo, and jumped at the chance to speak with her about Inheritance, her own hair journey, and learning to listen to your inner voice.

Naima Coster: Tell me about your earliest hair memory.

Elizabeth Acevedo: The first thing I think of is getting ready for kindergarten. My mom would set up a little chair in front of the TV and put on Gilligan’s Island. I loved Gilligan’s Island, probably because I had to. She would get the jade green hair pomade, and I would cry so much while she was doing my hair, untangling, doing moñitos, and braiding. I did not like getting my hair done.

NC: These memories are so fraught. I remember people always commented on how my mother did my hair so beautifully. It was a sign to the world that I was well-cared for. But I also hated getting my hair done. Will you take us a little further from that memory and share more of your hair story?

EA: My mom didn’t let me get my hair straightened until I was 10. It was a rite of passage. I remember immediately running upstairs to show off to my older friend, Rosita, that I, too, had joined the club of straight hair. There was just so much pride. My hair was thick, but it was also really long. There was a lot ingrained by the amount of attention I would get. I remember turning 16 on a school trip to Spain. I’d walk down the street and men would yell, “Negrita con el pelo largo!” [Black girl with the long hair!]. It was a strange exoticization.

It wasn’t until years later when I completely stopped straightening my hair that I could see my full curl. Now I’m at an age where I’m seeing it change again. It’s odd to be at a point where I’ve accepted and fully love its texture, and it’s getting looser in some parts and gray in some parts.

NC: Inheritance started as a spoken word piece you wrote 13 years ago called “Hair.” What was the first seed of this poem?

EA: When I was a senior in college, I started dating this guy who was so kind and smart, really special. I went home for winter break and sat down my mom and told her, “I’ve fallen in love.” We started having this conversation, and she said, “What race is he?” And I said, “He’s Black American from North Carolina.” It hurt so much to be telling someone that I was deeply in love and to get questions like, “Why would two oppressed people come together? Culturally, how are you two going to connect? What about your children? Have you thought about how this is going to be harder on them?” And then hair texture came up! I was so angry.

For my honors thesis I did a one-woman show that was all poems. I ended up writing this hair poem directly in response to feeling like I didn’t have enough Spanish to talk to my family and ask, “Have you thought about what you’ve internalized?” My parents weren’t taught anything about colonialism. It was so hard. I felt like, I want you to be better than this. I want you to know more than this. I don’t want to be the one teaching you.

It wasn’t until five years later when I was in the slam scene in D.C. that the hair poem went viral. It goes viral again every couple years. With The Crown Act, it got a new life. But I realized that maybe there was something else the poem could offer if I revised it. It’s not just my mother that tells me to fix my hair. It’s that her mother told her. It’s that society tells us. It’s that workplaces tell employees. It’s that schools tell students.

NC: A few years ago, a Dominican relative read an essay I wrote about embracing my curly hair, and she told me it had never occurred to her that hair straightening was about proximity to whiteness. My white editor for that piece also had difficulty with that idea and asked me, “But what is it about straight hair, besides proximity to whiteness, that made it so desirable to your family?” And I had to say, “No, that’s it. It’s just that.”

EA: I agree it’s entirely about proximity to whiteness. There’s a reason why I wanted green contacts when I was little and to dye my hair blonde. I remember I would stand in front of the mirror after washing my hair and I would pull it down and hold it like, Maybe if I just hold my hair like this, it’ll stay straight. It was so I could look more like the people who were considered beautiful in the world, the models. Those people were all white.

NC: Inheritance is remarkable because it’s so clearly fueled by both anger and care. And it feels so rooted in a particularly Dominican preoccupation with hair. What, if anything, are you saying to Dominicans in this book?

EA: The Dominican relationship with hair is so specific—a salon every two or three blocks, this belief that anyone can go in the salon and come back with straight hair. The Dominican Republic was the first place on this side of the world that was colonized. It has the longest history of any Latin American country with Europe and with whiteness. This book is a love letter to my then-boyfriend now-husband, but also to Dominicans who have worked and studied to know themselves and their history, to find language to speak back. We’re not alone. It’s not just your household. We can stand here together and say, “We all deserve a better understanding of ourselves. Our ancestors deserve better homage than the one we’ve been giving them.”

NC: In Inheritance, you write about future generations, “children of dusk skin and brilliant eyes” who will love themselves from the moment they’re born. What do you see as self-love?

EA: Self-love is knowing that you have value regardless of your hair texture, the width of your nose, the width of your waist. These things are superficial in comparison to your personhood.

NC: How are you continuing this work of unlearning toxic beauty standards in your life?

EA: It’s been really helpful to work the last few years on amplifying my inner voice. Ancestor worship, particularly within Ifa, teaches you that we choose this life. We come to earth with our own God in our body. We silence that God and listen to everyone else. The philosophy that we already come here with a wise and knowledgeable voice has helped me be less disrespectful to my inner voice.

I still struggle with weight and wanting to look a particular way. I was raised in chronic dieting culture. Thankfully, I’ve gotten to a place where I love my hair and nothing in me desires to be different. But I do think there are other parts of myself where I’m constantly reminded just how human I am and how tender I have to be towards myself. The God can get as loud as it wants, and I’m just like, “I can’t hear you right now, I’m in my feelings.” But I’m learning how to quiet the anxious voices and hear the voice that is reminding me that I’m valuable. I have a purpose.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io