Today’s Supreme Court is a threat to democracy — but activists plan to fight back

The Supreme Court is a supreme threat to American democracy. That was Abraham Lincoln’s view in light of the Dred Scott decision, expressed in his First Inaugural Address. And it was vividly illustrated after Lincoln’s assassination, when the Civil War amendments and civil rights legislation passed by Congress were effectively nullified by the Supreme Court, enabling former Confederates and other white supremacists to destroy the possibility of multiracial democracy for almost a century. “Our democracy suffers when an unelected group of lawyers take away our ability to govern ourselves,” as Harvard Law professor Nikolas Bowie wrote in 2021, based on his testimony before the do-nothing Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States.

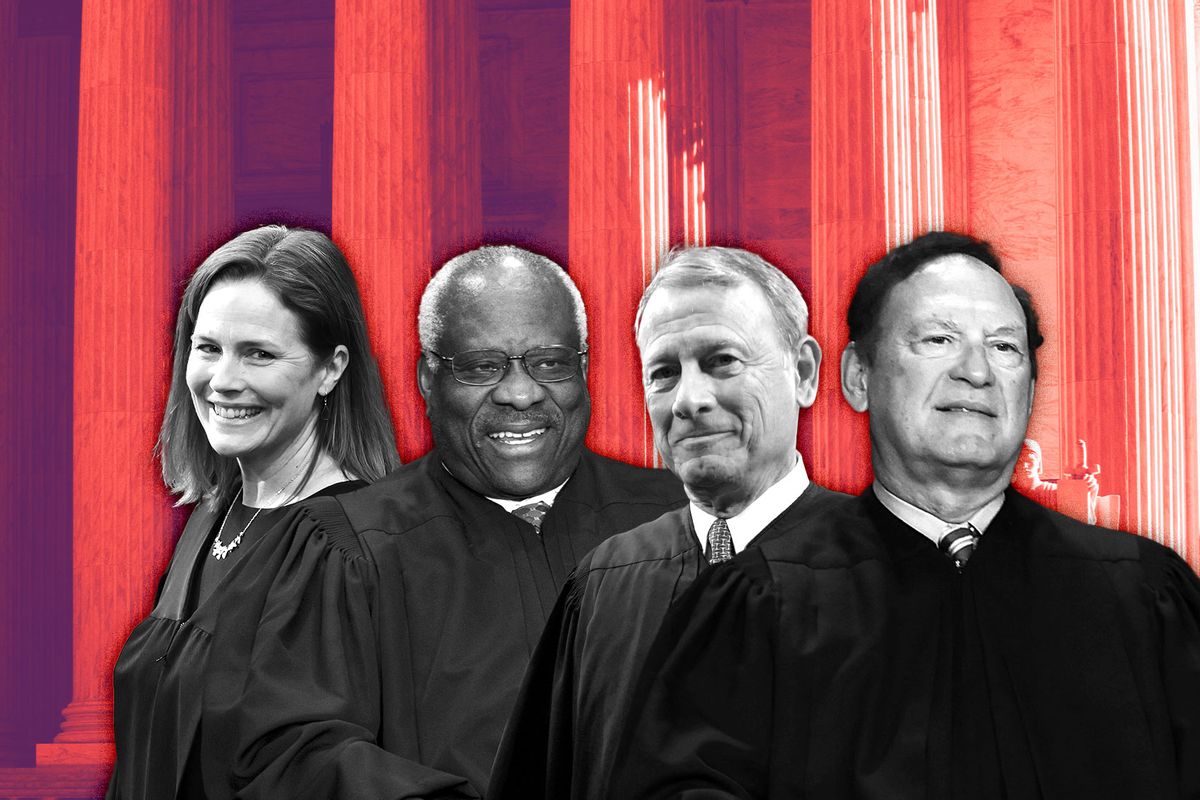

Since then, the Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, which overturned the precedent of Roe v. Wade, has brought Bowie’s point home with a vengeance. But it’s not just about abortion. On guns, environmental protection, discrimination, labor rights, affirmative action, student debt relief and numerous other issues, Mitch McConnell’s court-packing scheme and Donald Trump’s appointments have succeeded in dramatically undercutting Americans’ people’s capacity for self-government and the promotion of “the general welfare” promised in the preamble to the U.S. Constitution.

While the electoral backlash against Dobbs has been heartening, that’s essentially a reaction to the most alarming and personally invasive Supreme Court decision, not a proactive effort to dismantle the source of the threat. That’s why the new online lecture and discussion course, “What to Do About the Courts,” feels so important: It’s an effort to begin laying the groundwork for fundamental court reform. It’s a collaboration between the Law and Political Economy Project and the People’s Parity Project which featured Bowie as its leadoff lecturer on Jan. 30. A second session, looking at the history of reform efforts, was held Feb. 20.

“This is really core to what our organizations are doing and how we’re thinking about the work that we need to be engaged in for many years to come,” PPP executive director Molly Coleman told Salon. The online venue, she said, made it possible to “open this up quite a bit more than if we had done this as an in-person meeting group on a law school campus.”

The discussion component is critical, according to LPEP executive director Corinne Blalock: “It really does reflect our theory of change and how we understand how ideas move in the world.”

“We didn’t want this to just be a lecture series,” Coleman added. “Court reform should be something that’s built by the people. Part of this project is thinking about how we end judicial supremacy, how we make sure that the people have power, and not just unelected, unaccountable judges. We would be remiss if that wasn’t modeled in our programming.”

“Court reform should be something that’s built by the people. Part of this project is thinking about how we end judicial supremacy, how we make sure that the people have power, not just unelected, unaccountable judges.”

For generations, Americans have largely been blind to the Supreme Court’s profoundly anti-democratic character, because under former Chief Justice Earl Warren, the court was instrumental in reversing the post-Reconstruction destruction of democracy, most notably with the landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, which officially ended school segregation. But however significant Brown was in cultural and historic terms, in reality it only reduced segregation and certainly did not restore multiracial democracy. Congress began to do that with the 1965 Voting Rights Act — but nearly 50 years later, in Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court undid much of that law and once again began undermining democracy.

The halo effect around the Supreme Court, resulting from the Brown decision and the Warren court’s legacy more broadly — which continued into the 1970s with Roe v. Wade — was finally shattered for most attentive Americans by the Dobbs decision in 2022. Now, perhaps, Bowie’s unheeded warning a year before that may get the hearing it deserves, fleshed out by a range of possible court reforms that have been considered, implemented in the past (the subject of the course’s second session) or modeled elsewhere by healthier democracies (the subject of its upcoming third one).

“Really thinking about transforming the court felt politically inconceivable a few years ago,” said Blalock. “There were certainly scholars who felt the urgency, but we needed the material stakes to really connect it to people’s lives. With all the atrocious things that the Supreme Court has done recently, that piece has sort of been done for us. So our role is helping people connect that to a set of political ideas.”

There’s another and perhaps larger concern, Blalock continued. “For everyone on the left or left of center who’s thinking about transformative change, whether it’s climate change, reproductive rights or labor, it feels like the Supreme Court is looming,” she said. “We felt that our two organizations were particularly well-suited to step in and help connect the dots.”

“Despite this moment where the Supreme Court is at the center of so many conversations, despite a lot of excitement and energy around the possibility of court reform, there is a lack of information about what court reform can look like,” Coleman added. “Even folks who are living and breathing this work in advocacy spaces might be talking about expansion or might be talking about ethics reform, but so many of these other reforms that have been tried in the past haven’t entered the mainstream conversation. We felt there was an important void to fill, to take some of these ideas that are being discussed in the legal academy or by historians and bring them to the mainstream of progressive organizing spaces.”

The series began with Bowie addressing the foundation of the problem: the wildly disproportionate power of the Supreme Court, where five individuals can effectively thwart the will of 340 million citizens. Because judicial supremacy is so deeply ingrained in our system, people tend to assume it’s enshrined in the Constitution. It’s not. Lawyers are taught that it derives from the Supreme Court’s legendary 1803 decision Marbury v. Madison, but they’re generally not taught the larger story that casts the decision in a questionable partisan light. One might describe it, in fact, as a judicial coup.

As Bowie recounted, when the Federalist government under President John Adams passed the wildly unconstitutional Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798, the opposing party led by Thomas Jefferson didn’t turn to the courts. “Federal judges were just as partisan, just as committed to stamping out political opposition, as anyone else,” Bowie said. “So Jefferson’s party ended up getting rid of this law not by going to court, but by winning an election.”

In the lame-duck session that followed Jefferson’s victory in the controversial election of 1800, Adams and the Federalists created a bunch of new federal courts and packed them with supportive judges. That included Adams’ appointment of John Marshall, the outgoing secretary of state, as chief justice of the Supreme Court. After that, Bowie said, Jefferson’s party proposed a bill to destroy or undo all these new courts, which led to fierce debate:

Federalists responded [that] federal courts need to have this power to strike down federal laws. If Congress can simply get rid of the courts, then federal courts won’t have this power anymore. And for Jefferson’s party in Congress, they thought the idea that federal courts would strike down federal laws was this crazy innovation. Just a really bad idea and obviously partisan in motivation. … They thought there was nothing in the Constitution that says a federal judge can strike down a federal law. It would be a really weird distribution of power to give federal judges this control.

In the wake of that debate, Bowie said, Marshall authored the famous majority opinion in Marbury v. Madison, which “effectively just parroted the Federalist position from Congress.” In short, the position held by a minority in Congress became the law of the land — and not on some narrow legalistic point, but on the fundamental question of who is allowed to interpret the Constitution.

Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln, revered today as the founders of our two major parties, vehemently rejected judicial supremacy. It’s time for 21st-century Americans to seriously consider doing the same.

That remained a purely theoretical issue for more than 50 years. “Marshall didn’t end up disagreeing with Congress about the constitutionality of any legislation for the remainder of his term,” Bowie said. Then came the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which struck down the Missouri Compromise and denied Congress the right to prohibit slavery in the nation’s territories. This became a defining issue for the newly-formed Republican Party, which didn’t just shrug and accept it. As Bowie put it, “They responded, ‘What is the court doing? The court should not have this power,’” and ran on a platform “that repudiated the court’s power to decide this constitutional question.” After Lincoln was elected in 1860, “he and Congress passed legislation that did precisely what the Supreme Court said Congress could not do.”

There was certainly much more to Bowie’s presentation — and much more Supreme Court mischief that undermined the rights of Black Americans for generations — but that should be sufficient to show that our meek modern-day acceptance of judicial supremacy rests upon a profound ignorance of our own history. Both Jefferson and Lincoln, revered today as the founders of our two major parties, vehemently rejected judicial supremacy. It’s time for 21st-century Americans to seriously consider doing the same — or at the very least, to place significant limitations on it. The question, of course, is exactly how to limit or replace judicial supremacy, and what specific reforms can get us there.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

The February session of “What to Do About the Courts” began to answer those questions, looking into the history of court-disempowering reforms and proposals, with professors Samuel Moyn of Yale and William Forbath of the University of Texas. Moyn cited a number of reform ideas:

- Popular overrides of court decisions by referendum, as proposed by Theodore Roosevelt in his 1912 third-party presidential campaign.

- “Jurisdiction stripping,” meaning laws that limit the court’s jurisdiction over certain kinds of statutes.

- A supermajority requirement, meaning a bare majority of five justices could not invalidate laws passed by Congress, as proposed by progressive Sen. William Borah in 1923.

- Congressional authority to override any Supreme Court decision by a two-thirds vote, as proposed by Sen. Robert La Follette Sr. in his 1924 third-party presidential campaign.

- Prohibiting federal court injunctions in labor disputes, as mandated by the 1932 Norris–La Guardia Act.

Forbath looked more closely at the history of labor law: how the growth of a national economy increased the use of secondary strikes and boycotts, how common law and the Sherman Anti-Trust Act were used to declare them illegal and how that, along with court-sanctioned state violence, “inspired a decades-long, high-profile campaign of official union defiance of anti-strike and anti-boycott decrees,” undergirded by “a richly elaborated moral and constitutional order, a rival order built on the First and 13th amendments.” That movement declared, Forbath said, that “courts were quite literally creating property rights in man and elevating property rights over human rights.”

During the 1920s, Forbath continued, there were “constant calls and dozens of bills and proposals for laws and amendments to the Constitution that would enact what we call court reform. They brought movement constitutionalism to the halls of Congress,” resulting in the aforementioned Norris-La Guardia Act, even before FDR’s New Deal. That came about in part, Forbath said, because the judiciary had “squander[ed] its own legitimacy. Too many working-class Americans had come to see the courts for what they were: They were the place where the ruling class went to rule, dispensing class-bound decisions in the name of the Constitution.”

That kind of keen historical awareness, vigilance and activism may well be needed today. Arguably that shouldn’t be difficult to ignite, given the current radical Supreme Court and its recent actions. It may be much more difficult to create a unified movement with a clear vision for change. Divisions. to be sure, existed in earlier eras as well. “Back in the early 20th century, there was a rift between Black freedom organizations like the NAACP and labor and progressives who were most invested in labor reforms,” Forbath said. While the latter groups wanted to disempower the courts, the Black freedom movement largely did not, because the courts — however inadequate they were — appeared to be its most reliable allies.

By the Great Depression, “many working-class Americans had come to see the courts for what they were: The place where the ruling class went to rule, dispensing class-bound decisions in the name of the Constitution.”

That particular division no longer applies, but there are undeniably different priorities for different constituencies that could fragment reform efforts. More broadly, Forbath asked: “Do we want movement justices and judges, as brash in their way as the right-wing movement justices today? Or do you want more technocratic judges, committed above all to judicial restraint and a fair reading of progressive statutes?” The answer is not immediately obvious.

The seminar’s next session, Blalock said, will be “on the international and comparative perspective, which helps make this all feel so much more doable, particularly when for so long these have been treated like radically fringe ideas. After that, we’re going to dig a little more into the weeds about what the options are [and] really walk through the specific nature of how the reform would work. The final session is going to be on how we build a movement around this. We’re bringing in Astra Taylor from the Debt Collective, in conversation with Sabeel Rahman, who comes from more the government policy side, to talk about how we take these ideas forward beyond the reading group.”

So far, the feedback has been “alarmingly positive,” Coleman said. “The biggest thing we’re hearing is that even current law students aren’t hearing these ideas on their campus. They really feel that they’re getting something unique in this space [and] they’re really excited to bring it back to broader communities.” Beyond law school campuses, there are leaders in progressive organizations who “want every single person they work with to be at the next iteration of the reading group,” she said. “People want more folks to know what conversations are happening. That’s been pretty exciting.”

While attorneys, law students and activists are important audiences for these ideas, there’s also a need for broader conceptual, narrative and communications work aimed at a general audience. The right has successfully unified under the rhetoric of constitutional “originalism,” regardless of how vacuous that idea is in practice (Salon stories here and here). Conservative power is grounded in conceptual simplicity, even though the right’s ideas have proven inherently inadequate to the complexity of the modern world. To counter it, liberals and progressives must address that complexity — real history and real science, not myths — while heeding Einstein’s advice: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” In short, the progressive movement needs a counternarrative of its own, although identifying just one narrative might prove impossible.

One possible narrative, alluded to above, is to focus on the constitutional concept of “general welfare,” articulated in terms of public goods, an underlying logic laid out in Donald Cohen and Allen Mikalean’s 2022 book “The Privatization of Everything.” Another possibility is to focus on public health, which, as I argued in 2021, can “serve as a long-term, overarching framework to reframe our politics, to provide us with new common sense in addressing a wide range of diverse issues by highlighting common themes and connecting what works.”

Other narratives are surely possible. But it’s crucial that they encompass those four elements: common sense, a wide range of diverse issues, common themes and a pragmatic focus on what works. It’s no accident that the common law tradition encompasses those central themes. The promise of “What to Do About the Courts” is that history teaches us that change is possible and we can make it happen: Once legal scholars and activists on the left have fashioned the right framework, they believe they’ll have the wind at their backs.

Read more

from Paul Rosenberg on politics, power and history