How liberalism sabotaged itself: Are Cold War intellectuals to blame?

“Cold War liberalism was a catastrophe — for liberalism,” Yale historian Samuel Moyn argues in his new book “Liberalism Against Itself: Cold War Intellectuals and the Making of Our Times.” But Moyn never successfully defines either term, so in important ways his argument never gets off the ground. He does, however, succeed in raising awareness of how the moral confusion of so many liberals today stems from the early Cold War era and the events that preceded it. It’s a selective view — de-emphasizing race, for instance, in a period when it was central to both global and domestic politics — but the underlying dynamics of liberal self-sabotage still hold important lessons.

At the same time that “liberals around the world were building the largest — as well as the most most egalitarian and redistributive — liberal states that had ever existed,” Moyn writes, political theorists and historians like Judith Shklar, Isaiah Berlin, Karl Popper, Hannah Arendt, Gertrude Himmelfarb and Lionel Trilling (each the subject of separate chapters) were radically downsizing what liberalism had traditionally meant. He argues they abandoned “many of liberalism’s central features before the Cold War came —above all its perfectionism and its progressivism,” instead “casting its truths as an embattled but noble creed that the free world had to preserve in a struggle against a totalitarian empire.”

In particular, these intellectuals disavowed both the Enlightenment and Romanticism, the dominant intellectual traditions of the previous two centuries, rewriting the liberal canon in the process. For them, “the beginning of wisdom seemed to be a spare commitment to freedom from state excess in an era of tyranny,” epitomized by Isaiah Berlin’s concept of “negative liberty.” In this view, liberalism was “no longer the agent of an unfolding plan to produce a better an more fulfilled humanity,” but rather “an elemental and eternal set of principles that required the renunciation of ‘progress,'” in the face of “dark and aggressive” human nature.

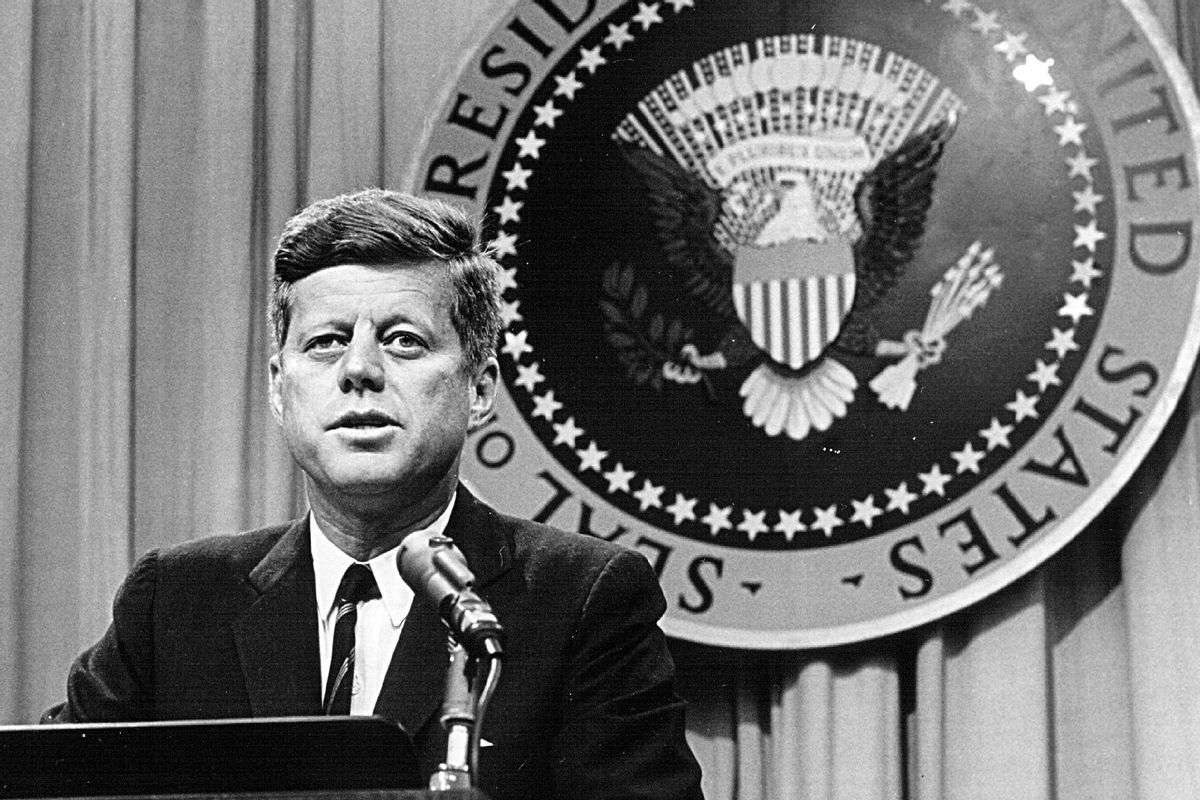

While the arguments he makes are incisive, the figures he highlights — important as they certainly were — hardly represent the whole of Cold War liberalism. Nor does he mention criticism of the Enlightenment from other sources, most notably “Dialectic of Enlightenment” by the Frankfurt School philosophers Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, who set out “to explain why humanity, instead of entering a truly human state, is sinking into a new kind of barbarism.” Many other Cold War liberals never gave up their belief in collective human progress, including the Cold War Democratic presidents Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson and the prominent intellectuals who advised them. In short, Moyn is describing a particular facet of Cold War liberalism, not the whole thing.

Moyn himself almost admits as much, writing that he chose figures like Berlin and Popper “in preference to more familiar Cold War sages” like Reinhold Niebuhr, Richard Hofstadter or Arthur Schlesinger Jr. “because they have been so neglected and therefore cast more unexpected light on critical features of their time.” Hannah Arendt, as Moyn agrees, “repeatedly declared she wasn’t a liberal” although her worldview was shaped in similar ways by the World War II era. WWII.

In fact, Schlesinger’s best-known book, “The Vital Center,” defended New Deal-style liberal democracy against both communism and fascism, and the fact that he’s mentioned only in passing is indicative of Moyn’s selective method. Other key figures directly involved in shaping Cold War liberalism go completely unmentioned, such as Walter Lippmann, who popularized the term “Cold War,” and George Kennan, who defined U.S. foreign policy and the strategy of “containment” with regard to Soviet Communism.

In Kennan’s “Long Telegram” — the ur-text of containment theory — he affirmed progressive ideals rather than abandoning them: “Much depends on health and vigor of our own society. We must formulate and put forward for other nations a much more positive and constructive picture of sort of world we would like to see than we have put forward in past.” In critiquing the Soviet system, moreover, Kennan recognized that democratic socialism was not the same thing: “No sane person has reason to doubt sincerity of moderate socialist leaders in Western countries. Nor is it fair to deny success of their efforts to improve conditions for working population whenever, as in Scandinavia, they have been given chance to show what they could do.”

It really isn’t true that Cold War liberals as a whole responded to the threat of totalitarianism by abandoning their allegiance to the Enlightenment, nor that they engaged in a broader rejection of progressive ideals.

In Moyn’s account, the Cold War conflict severed liberalism from a commitment to “emancipation and reason,” and “the aspiration to universal freedom and equality was denounced as a pretext for repression and violence.” This ignores the argument of Ira Katznelson’s 2003 “Desolation and Enlightenment,” focused on a community of scholars (including Arendt), dubbed the “political studies enlightenment,” who “undertook to address radical evil without losing the Enlightenment.”

These intellectuals “recognized that Hitler’s and Stalin’s focus on planned rationality had dressed their regimes in Enlightenment clothing, even claiming at times to be its saviors,” Katznelson writes, but “they thought the various totalitarian projects, despite their mimetic qualities, represented the negation of Enlightenment far more than its authentic culmination.”

In short, it really isn’t true that Cold War liberals as a whole responded to the threat of totalitarianism by abandoning their allegiance to the Enlightenment. Nor did they engage in a broader rejection of progressive ideals quite the way Moyn claims. He marshals strong arguments about how specific Cold War liberals responded in these ways, he makes no serious effort to demonstrate how broadly these responses were shared.

Moyn makes no attempt, for example, to measure how citations, article subjects or course offerings change, whether in whole fields, or at specific institutions — the kind of evidence of canonical change you’d expect to see, given Moyn’s central argument: “The first half of this book explores Cold War liberalism’s anticanon,” meaning anathemized movements, figures and books, from the Enlightenment and Rousseau through Hegel and Marx. “The second half turns to the substitutions,” such as Lord Acton or Sigmund Freud, “that were proposed to orient liberals for the tragic future disabused of emancipatory hope.”

Moyn’s arguments about his “iconic” examples, Isaiah Berlin and Karl Popper, are more satisfying than his larger historical account. Berlin’s “more jaundiced understanding of the Enlightenment … was built gradually across the 1950s and into the 1960s,” he writes. “Berlin’s maturation across the era made essential room for the disquieting possibility that the Enlightenment was itself to blame for the worst perversions of twentieth-century politics, especially on the left.” Berlin deployed “an increasingly familiar, not to say repetitious, strategy,” Moyn argues: He denounced “the Enlightenment in public for spawning the Soviet Union, and then reassure aggrieved or worried correspondents that the Enlightenment mattered for his own liberalism, too.”

Moyn writes that Berlin expressed “not merely fascination with but a kind of affectionate tolerance for the Enlightenment’s right-wing scourges, emphasizing the correctives they brought in spite of their own contributions to the political horrors of the twentieth century.” That pattern seems disturbingly familiar today, even if the specifics differ. The so-called liberal media overflows with voices with tolerance for the extreme right and scorn for the left, as if completely oblivious to the fact that this asymmetric stance undermines the supposed principles of liberalism.

With Popper, we encounter Moyn’s best case study of the way contingent circumstances led this faction of Cold War liberals so badly astray. This was doubly true of Popper’s two influential works from the World War II era, “The Poverty of Historicism” and “The Open Society and Its Enemies.” Popper viewed the rise of Nazism through the parochial lens of Austrian left-right politics, Moyn writes, “blaming Hitler’s victory on some of its victims,” specifically socialists. This was compounded by Popper’s wartime exile in New Zealand, far removed from diverse viewpoints and robust debates. According to Moyn, Popper’s critique of Hegel and Marx “relied on the spottiest possible knowledge of their works.”

Moyn deftly critiques the way Popper attacked liberal historicism, meaning “the broad view that history is a forum of opportunity for the acquisition and institutionalization of freedom,” by defining it so narrowly as to be restrictive and meaningless. But he passes over Popper’s deeper individualist epistemological mistake, embedded in his philosophy of science, which provided a foundation for his attack on historicism. As Naomi Oreskes explains in “Why Trust Science?” and reiterated in a Salon interview, Popper’s claim that “the good scientist should always be looking for refutations to his theories” is not how actual scientists work, and has been supplanted by Ludwik Fleck’s model of thought collectives, centering the community structures of science.

Modern liberalism is commonly conceived of in individualist terms, particularly in terms of individual rights. But the more densely interconnected society becomes, the more clearly it needs to be conceived in social terms.

Perhaps in the 18th century an individualist account of science might have seemed plausible, but by the time of the Cold War, after the Manhattan Project, it was clearly absurd. The birth of Big Science came in precisely that period, yet Popper’s account dominated the philosophy of science and underwrote his attack on historicism.

Moyn misses this, which seems symptomatic of his own individualistic orientation. His book is organized into chapters devoted to single individuals. He certainly discusses the interplay of individuals’ insights into one another’s arguments, which enriches his story but does not translate into a truly social account.

Here we come to the crux of the matter: Modern liberalism is commonly conceived of in individualist terms, particularly in terms of individual rights. But the more densely interconnected society becomes, the more clearly it needs to be conceived in social terms — as Britain’s “New Liberals” and others argued in the 19th century. But they were hardly the first. A nearly forgotten Cold War-era text, Eric Alfred Havelock’s 1957 “Liberal Temper in Greek Politics,” argues that the pre-Socratic Greeks developed a sweeping philosophical vision of physical, biological, social and political evolution that arguably had all the hallmarks of liberalism, except for being conceived in individualist terms.

As far as modern liberalism is concerned, John Locke’s argument in his “Second Treatise” is fundamentally pro-social, in a sense that is often misunderstood. In the purported “state of nature,” Locke contends, everyone enjoyed limitless natural rights, but none of them was secure. To secure those rights, human beings created government — the most basic pro-social act. So in this fundamental sense, liberalism has always been a social philosophy, albeit one that protects individual rights.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Cold War liberalism struggled with the evolving nature of what that meant, often seen in terms of who had which rights, and when or whether they would be extended to women, Black people, developing nations and so on. It should be self-evident that these particular, concrete social struggles were at least as central to Cold War liberalism as the political theorizing that Moyn discusses, particularly in the early Cold War era, when many major intellectuals were largely “fearful, cautious, distracted, or simply indifferent,” as Carol Polsgrove argues in “Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement” — a picture consistent with Moyn’s argument. A critical look at how such ideas were received by Cold War liberals would certainly have enriched Moyn’s thesis, and grounded it more directly in real-world politics.

Finally, Moyn’s book contains the seeds of at least three significant arguments that cry out for further elaboration. First, while he spends most of the book ignoring the obvious fact that his subjects are essentially all European Jewish refugees, he briefly places a profound contradiction at center stage: “So we must face squarely that Cold War liberals had a geographical morality. They offered Cold War libertarianism for the transatlantic ‘West,’ a Hegelian statism (with violence if necessary) in their Zionist politics, and a caustic skepticism about the fate of freedom in either form elsewhere, based on an implicitly hierarchical set of assumptions about the world’s peoples.” This formulation is compelling, but this brief mention of Zionism — a controversial ideology, but unquestionably a progressive one — cries out for a much fuller discussion.

The seeds of two other arguments can be found in a single statement when Moyn writes, “Cold War liberalism also gave rise to successor movements that have defined our times in even more restrictive terms: neoliberalism and neoconservatism,” He is surely right to cite the latter, as the inclusion of prominent neocon Gertrude Himmelfarb makes clear, though he makes no effort to show how that trajectory unfolded. He describes Himmelfarb’s effort to elevate Lord Acton into liberalism’s new canon by calling him “a perfect Cold War icon,” who modeled a way “to approach history and politics from the perspective of eternal commitments, in the name of a liberalism beyond the terms of historicism.”

Moyn is simply mistaken that Cold War liberalism gave rise to neoliberalism, as far as intellectual origins are concerned. But in another, arguably more significant sense, he gets it right.

Himmelfarb was first attracted to Acton because he stood out as more liberal than his Victorian peers, but Acton became a gateway drug for her obsession with Victorians in general, whom she came to see as morally superior. (She wrote at least four books about Victorian thought, morality and culture.) Exploring Himmelfarb’s peculiar trajectory might have enabled Moyn to turn his claim that Cold War liberalism gave rise to neoconservatism into a compelling and original argument — a road not taken.

His parallel claim about neoliberalism is more complicated. Moyn is simply mistaken that Cold War liberalism gave rise to neoliberalism, as far as intellectual origins are concerned. As Quinn Slobodian shows in “Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism,” what we now call neoliberalism first emerged in the 1920s in response to the Great War’s disruptions of the global financial system. But Moyn is not mistaken in another, arguably more significant sense. If Cold War liberals did not, as a whole, abandon a belief in collective human progress, they generally did abandon any effort to articulate a coherent public account of what it might look like — which had profound political consequences, and opened the door for neoliberalism to take center stage.

This was highlighted by public opinion pioneers Lloyd Free and Hadley Cantril in their 1967 study, “The Political Beliefs of Americans,” which found as a profound disconnect between a strong and widespread preference for liberal policies and a generally tendency to identify with conservative philosophy. The authors themselves called it “almost schizoid,” observing that nearly half of all Americans were “ideological conservatives” even though nearly two-thirds were “operational liberals,” favoring increased spending on education, housing, health care and campaigns against poverty. The problem, in part, was that there was no readymade set of liberal principles to ask people about, but there appeared to be a clear set of “conservative” principles, which amounted to placing individual initiative above government interference — in short, Isaiah Berlin’s “negative liberty.”

Free and Cantril write:

There is little doubt that the time has come for a restatement of American ideology to bring it in line with what the great majority of people want and approve. Such a statement, with the right symbols incorporated, would focus people’s wants, hopes, and beliefs, and provide a guide and platform to enable the American people to implement their political desires in a more intelligent, direct, and consistent manner.

Even if Moyn is wrong to claim that Cold War liberals uniformly turned their backs on earlier traditions supporting broadly shared human progress, that tendency was certainly part of a broader retreat from a forceful progressive vision, resulting in the conundrum Free and Cantril describe. The pernicious influence of major Cold War liberal thinkers still resonates today, not just for their specific arguments and their efforts to rewrite the past, but also for their reactionary attitude toward the legacy of Enlightenment, leading us far too close to its negation.

Read more

from Paul Rosenberg on history and politics