The apps getting your wardrobe back under control

As a child growing up in Tunisia, Hasna Kourda was taught how to make and care for her clothes by her grandparents.

“We come from a little island in the south where everything needed to be managed in a circular way – water, food and clothing,” says Ms Kourda. “We learned how to make things from the first step.”

When she moved to Europe in the early 2000s to study at a French business school, Ms Kourda says she was shocked by the amount of clothing people were buying.

“I naively thought people had these incredible social lives and needed all these things. Then I realised there was a very heavy throwaway culture.”

If people aren’t discarding clothes after wearing them just a few times, then they are often leaving them at the back of their wardrobe never to be worn again. One global study from a few years ago found that people don’t wear at least half of the clothes they own.

Ms Kourda was never able to shake her unease at all this waste, and after a number of years working for various firms in the fashion industry she decided she would try to do something to prevent it.

In 2017, and by then based in London, she started raising funds to launch her own fashion technology company, to help people make the most out of their clothes.

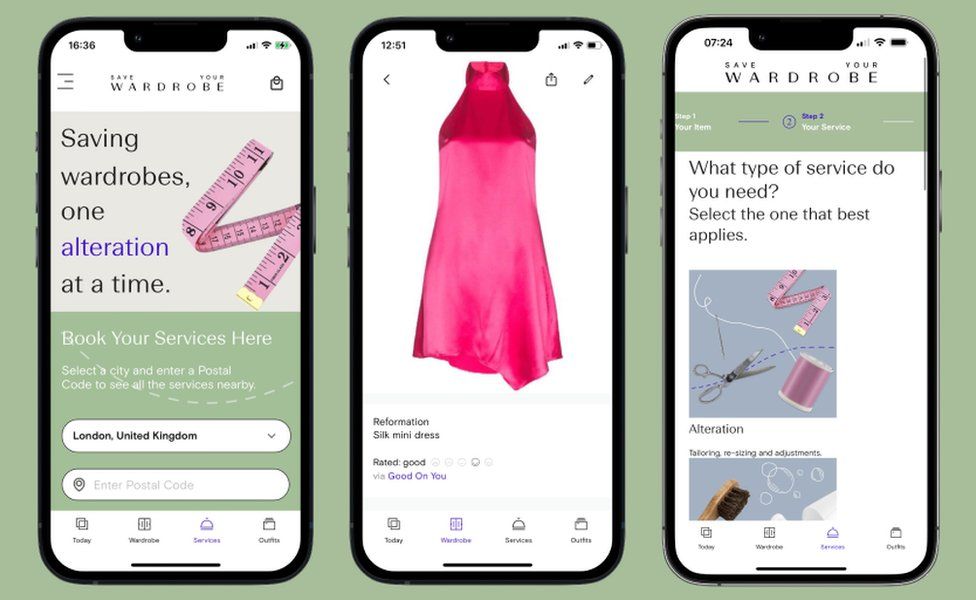

Launched in 2020, Save Your Wardrobe is an app that allows users to manage their clothes by creating a digital version of every item in their wardrobe.

Via the app, garments are scanned, identified and stored virtually. Then the app can remind you of everything you own, with the hope of getting unworn clothes back into use.

It also connects people to local services such as a dry cleaners, places where they can donate no longer wanted items, and repair and alteration shops to extend the life of their garments.

The Save Your Wardrobe app launched in March 2020, just as the pandemic hit. It has now been downloaded more than 100,000 times, says Ms Kourda.

Luxury fashion website FarFetch is an investor, and Save Your Wardrobe has also partnered with another such retailer, Zalando, to launch a clothing care and repair initiative. The app is currently free to use, but a premium version with advanced features is in the pipeline.

Rachel Kan, sustainability expert and founder of consultancy Circular Earth, believes that the cost of living crisis will lead many people to buy less clothing. “There will be a big shift towards minimalism,” she says.

Lin Kowalska is a Swedish entrepreneur and founder of Popswap, an app for swapping clothes. She believes technology companies like hers offer a way to reduce the fashion industry’s impact on the planet.

The extent of this hit on the world’s environment is surprisingly high. The fashion sector is responsible for between eight and 10% of annual global carbon emissions, according to the United Nations.

Millions of tonnes of textile waste is created annually and the equivalent of a truck load of old clothes is burnt or buried in landfill every second, research from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation calculates. That organisation campaigns for more textile recycling.

Popswap is a social media platform where users can show off their outfits, connect with people whose style they like, and swap clothes with them. “Just like on Tinder, the build a relationship with each other and match based on style and swap outfits,” explains Ms Kowalska.

Previously working in marketing, she got the idea for Popswap after a conversation with friends about accessing each other’s wardrobes. Ms Kowalska then asked tech developers she knew to create an app to help her and her friends exchange clothes.

Popswap launched in August 2020 and since then it has gained 40,000 users, with more than 100,000 garments swapped through the app to date.

Most of Popswap’s current users are based in Sweden, and swap clothes with people living nearby. Ms Kowalska intends to expand the app into cities around the world, including London.

The majority of the app’s users are 16 to 25-year-olds, also known as Generation Z. “Gen Z love it,” says Ms Kowalska.

Popswap is free for people to use, with the company making its money through premium subscriptions and advertising on the app. Popswap has also hosted clothes swapping events during Stockholm and Berlin fashion weeks.

“If we can find a way to make money from fashion without producing new clothes, that’s the solution,” says Ms Kowalska. “For that to happen, we need to collaborate across the industry and be more tech heavy.”

As Popswap’s main user age demographic shows, young people are embracing second-hand fashion. This is also backed up by reports. More than three quarters of 16 to 24-year-olds in the UK have either swapped fashion items with others, or would be interested in doing so, a 2020 study found.

Yet at the same time, mass-produced, cheap, poor-quality clothing, often now called “fast fashion”, continues to be popular with cash-strapped shoppers.

A 2022 report by ThredUp, a US-based second-hand fashion site, said that while sales of used clothing were soaring, 59% of fast-fashion shoppers said that it was a habit that was hard to quit.

To help people quit fast fashion, ThredUp recently launched an advertising campaign starring Stranger Things actress Priah Ferguson.

Anthony Marino, the president at ThredUp, says the company’s mission is to inspire people to think second-hand first. “We believe the sustainable fashion revolution is in full swing, thanks to disruptors like ThredUp who have given consumers easy ways to participate in the circular economy,” he adds.

ThredUp, which was founded in 2009, has become one of the largest online fashion resale sites for women and children’s clothes, selling more than 35,000 brands.

The company buys people’s used clothes in exchange for cash or store credit, then lists the clothing for sale on its website.

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

When the firm floated on the New York Stock Exchange in March 2021, it was valued at $1.3bn ($1bn). And last year the company partnered with luxury brand Tommy Hilfiger on a resale program.

“Our ultimate goal is to divert as many clothes as possible from landfill,” says Mr Marino. “The more that consumers, government and other industry stakeholders put pressure on fashion companies that are overproducing disposable fashion, the more they will be encouraged to change for the better.”

Circular Earth’s Ms Kan says that clothing tech firms such Save Your Wardrobe, Popswap and ThredUp are continuing to play a vital role in reducing pollution and waste in the fashion industry. “We need to be able to recirculate fashion in an effective and economic way, and fashion tech companies will be a really big part of that,” she says.