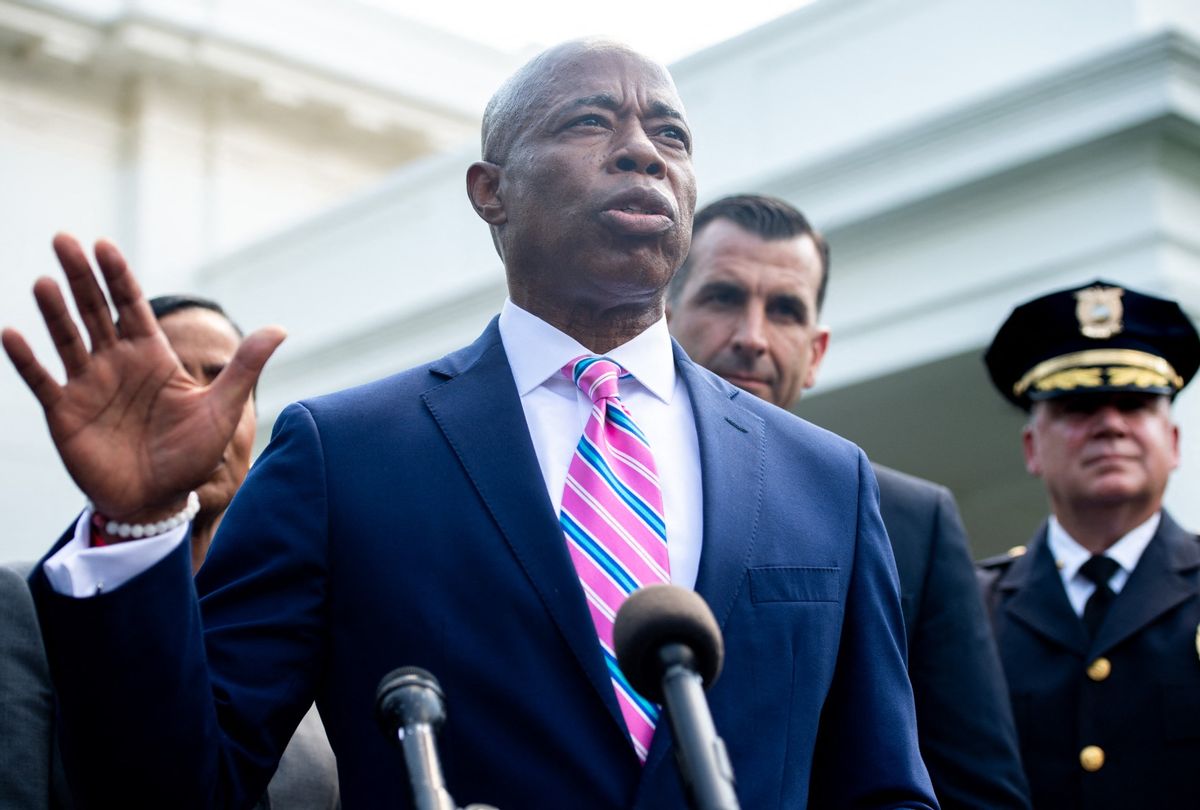

NYC Mayor Eric Adams’s terrible plan to forcibly hospitalize homeless people with mental illness

On Nov. 29, New York City Mayor Eric Adams declared at a press conference that his “compassion” driven response to the city’s homeless crisis would be to enhance the state’s existing authority to involuntary commit the mentally ill in their ranks to ensure people “in desperate need” were no longer allowed “to slip through the cracks.”

“As a city, we have a moral obligation to support our fellow New Yorkers and stop the decades-long practice of turning a blind eye towards those suffering from severe mental illness, especially those who pose a risk of harm to themselves,” Mayor Adams said. “It is not acceptable for us to see someone who clearly needs help and walk past them.”

Adams, himself a former NYPD officer with extensive experience in the subway system, blamed the deepening humanitarian crisis on the existence of “a gray area where policy, law, and accountability” had become “unclear”. This, he reasoned, led to a “culture of uncertainty” that had caused “untold suffering and deep frustration” that he proclaimed he would not “allow” to continue.

Not highlighted in the mayor’s City Hall rollout was reference to New York State’s decades-old decision to close mental health facilities and neighborhood hospitals — nor the ongoing choices, made amid the pandemic, by the city’s wealthiest private hospitals to close their inpatient psychiatric units. Nor was there a recognition of how the increasing scarcity of psychiatric care and beds came as tens of thousands of affordable housing units disappeared while city housing increasingly became a luxury good.

In the press release that accompanied his address were boiler plate testimonials supporting the policy from mayoral appointees including New York City Police Department (NYPD) Commissioner Keechant L. Sewell and Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) Commissioner Laura Kavanagh. Missing entirely was the real-world, street-smart perspectives of the thousands of first responders, transport workers, social workers and healthcare professionals on the front lines of the deepening humanitarian crisis that takes a real toll on them as well.

As a candidate for mayor, Eric Adams emphasized his working-class public union roots — and the unions responded with their endorsement of the then-Brooklyn Borough President. Yet as mayor, his approach to governing and labor relations has resembled the pro-business worldview of Mayor Michael Bloomberg where the unions were expected to fund their own cost of living raises with concessions and givebacks. This rightward branding to ‘make do’ comes as the city he leads continues to unravel from the lingering consequences of a mass death event, as well as everything else ranging from declining student test scores to a mass exodus of key municipal civil service titles from cops to paramedics.

Now, some of the sharpest and best-informed criticism of the mayor’s latest signature policy comes from the leadership of the unions that were his earliest and most ardent supporters. In a Dec. 7 New York Times op-ed, Anthony Almojera, a lieutenant paramedic with FDNY EMS, and vice president of the DC 37’s Uniformed E.M.S. Officers Union, Local 3621 described a dystopian street-scape where his colleagues have been assaulted and even murdered by emotionally disturbed individuals that are also homeless.

“I’m not opposed to taking mentally ill people in distress to the hospital; our ambulances do this all the time,” wrote Almojera. “But I know it’s unlikely to solve their problems. Hospitals are overwhelmed, so they sometimes try to shuffle patients to other facilities. Gov. Kathy Hochul has promised 50 extra beds for New York City’s psychiatric patients. We need far more to manage those patients who would qualify for involuntary hospitalization under Mr. Adams’s vague criteria.”

Almojera continues, “Mr. Adams says that under the new directive, this patient won’t be discharged until a plan is in place to connect the person with ongoing care. But the systems responsible for this care — sheltered housing, access to outpatient psychiatric care, social workers, a path to reintegration into society — are horribly inadequate. There aren’t enough shelters, there aren’t enough social workers, there aren’t enough outpatient facilities. So, people who no longer know how to care for themselves, who need their hands held through a complex process, are alone on the street once again.”

“Our ambulances are simply the entrance to a broken pipeline,” Almojera writes. “We have burned down the house of mental health in this city, and the people you see on the street are the survivors who staggered from the ashes.”

The veteran FDNY EMS officer and author of the memoir “Riding the Lightning: A Year in the Life of a New York City Paramedic” suggests that New York’s mayor look beyond “a superficial fix” to what is actually a national problem caused by a long “neglected” health care system and chronic underinvestment in “social services, housing and mental health care.”

According to the New York State Nurses Association [NYSNA], which represents 40,000 nurses, the contraction of available psychiatric beds has accelerated even as New York City sunk deeper into the latest crisis as COVID raged and killed tens of thousands of New Yorkers and over one million Americans.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York, Governor [Andrew] Cuomo suspended the Certificate of Need applications which require hospitals to go through a public process before closing or changing services,” according to a NYSNA fact sheet. “Consequently, hospital administrations have been emboldened, closing their inpatient psychiatric units, often without clarifying to nurses or the community whether these moves are temporary or permanent.”

NYSNA’s 2020 policy brief continues, “Private hospital systems like NY Presbyterian and Northwell are taking these services out of the community, despite decades of cuts to mental health care stemming from mergers and hospital closures. The Berger Commission and other efforts to shrink NYS hospital capacity, together with declining Medicaid reimbursements, and the reality that psychiatric patients simply aren’t as lucrative as other patients, have created powerful incentives for hospital systems to shed inpatient psychiatric beds.”

“Meanwhile, the city’s public hospital system and the correctional system are picking up the burden,” NYSNA observed. “This contributes a greater likelihood that individuals with serious mental illness will have a violent encounter with police. The acute underfunding of public hospitals means that the healthcare professionals in our public system are not provided the resources to treat this new influx of psychiatric patients, many of whom have complex diagnoses.”

At her Dec. 7 press conference before the City Council’s Stated Meeting, City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams was asked by Daily News reporter Michael Gartland if the Adams administration had offered the City Council any details on how the city would fund the additional psyche beds the new approach would likely require, she said the Council was “still waiting for a full, comprehensive plan.”

“The conversations do have to be much deeper,” Speaker Adams told reporters. “Conversations around mental health, preventative measures—the city’s need for deeper investments in our mental health infrastructure—how to deliver people the long-term help that they need. The first thing that comes to my mind is supportive housing. What are we going to do once we determine someone is going to be hospitalized or evaluated? What is the time frame?… It’s always going to come back to supportive housing.”

It’s impossible to have a real conversation about the homeless mental health crisis without examining how it’s a direct consequence of our winner take all scarcity-based housing market and for-profit health care system. Without addressing those issues the use of law enforcement to “improve” street conditions by forcibly taking the indigent mentally ill off of the street without a real plan becomes a blunt force instrument that’s only guaranteed to inflict more trauma.

In doing so, the city will be following a long tradition going back to the 1600s when England enacted it’s so-called Poor Laws that required vagrants to “be committed to a house of correction or fined.”

“The American colonies and state governments modeled their public assistance for the poor on the Elizabethan Poor Laws and the Law of Settlement and Removal,” according to the Virginia Commonwealth University’s Social Welfare History Project. While the mayor’s efforts no doubt springs from an authentic desire to relieve the suffering of the undomiciled mentally ill, it also re-enforces the public appearance that he’s taking strong action.

New York City-based sociologist Dr. Steven Pimpare is the founder and director of the Public Service & Nonprofit Leadership Program and a Faculty Fellow at the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire who previously taught at Columbia University, NYU, Simmons University, and the City University of New York. He is the author of Politics for Social Workers: A Practical Guide to Effecting Change, published in 2021 by Columbia University Press

“This is a quality-of-life problem for the affluent, not a humanitarian problem,” Pimpare said. “Demonizing the homeless is not new. There is no more manifest example of the failure of the system than bullying the vulnerable and criminalizing mental illness.”

Perhaps the Mayor would be well advised to consult more with the workers on the frontlines.