“You have to think about hope”: Author Silas House on democracy’s demise, climate refugees and dogs

Silas House is on the move.

The acclaimed novelist, creative nonfiction writer and professor is stepping in to teach some extra classes just after our call. Before then, there is a brief chase with an errant dog who has decided now is the time to make a break for it down a hill.

House’s characters are on the move too. The protagonist of his latest novel, “Lark Ascending” is a gay man in his early 20s named Lark who flees the United States with his family, seeking a safe haven in the wake of extreme climate change — and the extremism that has wracked the country, fundamentalism that makes Lark’s very existence as a queer man illegal. His family has their sights set on Ireland. But Lark is the only one to survive the difficult crossing. Destroyed by grief, in a destroyed world, Lark attempts to make a new life in the community of Glendalough, Ireland, and to assemble a family with a woman who has also lost deeply. And naturally his found family includes a beloved dog, a beagle named Seamus, too.

House is the author of six novels, most recently 2018’s “Southernmost,” as well as a book of creative nonfiction, “Something’s Rising,” co-authored with Jason Howard. He was an executive producer and one of the subjects of the film “Hillbilly,” a documentary that examines Appalachian stereotypes in media and culture and the exploitation of Appalachian people.

“I have always written my way out of trouble. “

Salon talked with House about the new novel, climate change refugees, American now and the America of dystopian fiction.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How would you describe your new novel “Lark Ascending”?

I think of it as an adventure story. To me, it’s a real “Odyssey” story. It’s a short book. But I think it has an epic feel to it. Because it takes place in lots of different locales, and there’s a big journey involved. There’s this transatlantic crossing. It deals with pretty huge themes of climate change disaster and the demise of democracy. Thematically, I feel like the book is all about grief. The lead character has lost everything. He’s lost the love of his life. He’s lost his family. He’s lost his country. The whole book grows out of really personal grief and a really sort of global grief. I started this book shortly after I lost my aunt. I was very close to her. She was a grandmother and mother figure to me, really foundational to me, as a person and as a writer. And I was just overwhelmed and flattened by my grief for her.

I have always written my way out of trouble. Anytime that I’m troubled or sad, I turned to writing. And so the novel, you know, I poured that grief out. At the same time. I mentioned a global sort of grief. I think over the last few years, a lot of us have felt that we’re losing our country, have felt like we’re witnessing the demise of democracy. I mean, from the time that I sold this novel until it would be published — women have fewer rights in that time span. I think that we can see how the country is changing. It’s not changing for the better and we’re mourning the loss of autonomy . . . Those things are definitely going on in the background.

But what’s important is the human story, the relationships that are playing out against that background. I have this young gay man who’s sort of alone in the world. His existence has been outlawed in the United States because of this fundamentalist uprising. What I really want the reader to take away from it is: here’s this man who’s just trying his best to be the best person he can be and survive. It seems like everything is against him. He creates a family for himself, which is all you can do.

And this is a departure for you. You haven’t written necessarily a dystopia before. Did you set out to write a dystopian novel? Or did the story just naturally take this shape?

No, and, you know, I’m not offended by that description at all. The book has been described that way, and that’s fine with me, but I’ve never thought of it that way. I always just thought of it as a literary novel that happened to be set 20 years in the future. And I really like the idea of mixing genre. Call it climate fiction, or dystopian, or literary fiction, or an adventure story – I want it to be all of those things. I just want it to be a rich, storytelling experience.

For most of the action of the book, Lark, the main character, is about 20 years old. But he’s telling this story as a very old man. I imagine him to be about 100 years old, telling it on his deathbed. For that reason, I think it does have a real storyteller quality to it. You definitely have been told a story. I wanted the narrative voice to have a timeless quality to it. Not exactly old-fashioned, but it doesn’t sound like a futuristic voice.

That’s interesting also, because it’s a journey narrative. And that’s a very traditional kind of story. Was it important for you to spend so much time on the journey?

Yes, I really wanted to write a book in which the characters are always in motion. And if I’ve done my job correctly, the reader feels that way too, so that the reader feels like it’s a real page-turner. I want it to be very literary and lyrical, but I also want it to move.

It is quite an epic journey that the characters take. Why did you choose Ireland as the place Lark would travel to?

In writing a book that’s set in the near future, you do have to do quite a bit of world-building, and you have to figure out the scenarios, exactly what has happened. And you, as the writer, you have to know a lot more of that than shows up on the page. Because if too much of it shows up on the page, it’s lost its mystery, and you can tell too much. But I had to know all that. I felt like it made sense for Ireland to be the place because the impetus for the disaster is climate. I feel like Ireland would be a place that was safer from this sort of climate catastrophe. But then I figured out that even if it was safe from the climate catastrophe, it would not be safe from the rise of fascism that happens in the world as a result of this climate catastrophe. That made sense to me because Ireland has for so many centuries been a country fighting for its autonomy, for its unity. It’s sort of the reverse immigration story, because we know so much about the way Irish people emigrated to the United States in the 1800s. And here we have Americans seeking refuge in Ireland.

One thing I really wanted to do in the book was make American readers or any reader think more, put themselves more in the shoes of refugees. I think we see news coverage of refugee crises in the world, and we’re sad about it, and we sort of shake our heads, and then we move on. And we feel pretty removed from it. I wanted to force us into their shoes more. To make the reader think about the refugee experience and how it feels to not [just] have only the clothes that are on your back, but also to not have a country. To have lost that as well.

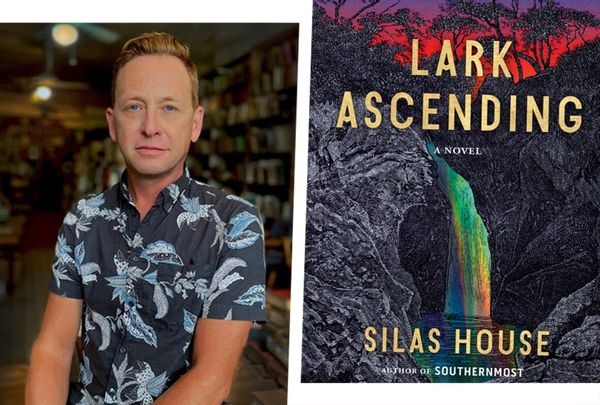

(1) Author Silas House and (r) “Lark Ascending,” available now from Algonquin Books. (C. Williams/Algonquin Books)You talked a little bit about Lark, and I’d love to talk about him a bit more. He’s a 20-year-old gay man. You’ve written from the point of view of younger men before. Why is it important for you to write from this voice?

(1) Author Silas House and (r) “Lark Ascending,” available now from Algonquin Books. (C. Williams/Algonquin Books)You talked a little bit about Lark, and I’d love to talk about him a bit more. He’s a 20-year-old gay man. You’ve written from the point of view of younger men before. Why is it important for you to write from this voice?

I wanted the narrator to be someone who couldn’t really remember the old world. He was a baby before everything collapsed, but he thinks back to this time right now that we’re living in. Those are the days of his infancy. I wanted him to be somewhat removed, and so he needed to be pretty young for that reason. I mean, I am a gay man. But I’ve written gay characters, main characters in plays and short stories — all of my writing except my novels. This is my seventh novel, but it’s my first gay protagonist.

“So often, love stories between men are rooted in violence.”

It just really made sense for this novel for him to be a young gay man. I feel like your main character should always be the one in trouble . . . I think so many gay stories have been told where the gay character is the person who’s in trouble. And this is the first one that felt new and different for me to tell that kind of story. For one thing, I don’t know of another adventure story that has a gay protagonist, at least in adult literature. I loved feeling like I was doing something new in that way. He’s on the run from these fundamentalist forces as a young gay man.

I also wanted to write a tender gay love story. So often, love stories between men are rooted in violence. And the love story between Arlo and Lark is very tender . . . they’re removed from all the violence that’s going on in the world, and they can just have this kind of pure, tender romance. That was another thing that I think there’s a lack of in our literature, gay love stories that aren’t absolutely angst-ridden. And this romance stuff isn’t controlled by the culture. Now, having said that, the culture catches up with them, but they do get to have that time together.

My editor would also probably be upset at me if I didn’t ask about the dog in the book. Why did you decide to have a dog and how did you create the character?

Couple reasons. Number one, I’m a dog person, and I have never not had a dog my entire life. The main reason though, is that this is a very dark, hopeless scenario, and having the dog gives the book a lot more joy. It gives it some light moments, and it inserts some life into the book. In fact, some of the chapters are told from the point of view of the dog. And so they’re in this really terrible situation, but the dog is a joyful creature, and the dog is full of wonder. The dog isn’t aware of its own mortality the way the human narrator is. And so it balances things out, I think, in a really pretty perfect way from my point of view, to where you don’t get so bogged down in the darkness.

The other thing is, I was reading a book about World War II, and I read that during the Blitz, people in London were told by the government that it would be more humane for their pets to put them down because they were so afraid there would be such widespread death, that the country would be full of cats and dogs just roaming everywhere, starving. So 750,000 pets were euthanized in the space of about a month, and I just thought what an eerie, incredibly sad thing that must be. I wanted to recreate that scenario in the book and just think about a world that was pretty much free of pets. And what a sad place that would be. But of course, this dog has survived by being really smart and joins up with Lark.

Lark finds company in unexpected places. Even in the destruction of this world, we can still find a friend.

Lark is in a situation where it’s very hard – it takes him almost the whole book to trust the woman that he encounters. But he trusts the dog right away. He needs somebody to love. And so the dog is that for him in the book.

Climate change is the impetus for the story. How do you think that writers or creative artists can help our understanding of climate change or underscore the importance of doing something about climate change?

“You can’t write a novel without being hopeful.”

It’s really hard to be a person in the world right now and not be thinking about that. It’s such a part of our lives now. You have to think about hope . . . We’re always saying, you know, “It’s too late. We can’t stop it now.” But at the same time, we have this notion that we can do some things to make it better for future generations. So on one hand, we know we’re going to have fight climate change, and there are going to be climate refugees. On the other hand, it’s not too late to try to make some dents in it. I guess the main thing is that I want people to read the book and think about what we can do, even if that just means to make somebody think about not leaving their water running all the time when they’re brushing their teeth or turning a light off. It can happen in small ways. I want people to be more conscious of all that. It’s something that I’m concerned with the same way I’m concerned with democracy. I tend to write about things that trouble me, that I care about.

And you never know where someone might be moved or changed or even learn something. Not everyone gets their news from the newspaper. You never know how you can reach someone.

For me, fiction has been more of a teacher than an entertainment to me. I mean, it’s been both, but I’ve learned so much from reading fiction. I always say that the book that has taught me more than any other is “The Color Purple” by Alice Walker. And that’s largely because it made me think about religion, it made me think about sexuality, gender, race, all this. I mean, everything that you can possibly think of, is covered in a book like “The Color Purple.”

Are there other writers that you return to, as kind of touchstones?

This book in particular was really inspired by adventure stories, like “Kidnapped” by Robert Louis Stevenson, “The Call of the Wild” by Jack London. This is a book that’s somewhat about the rise of fundamentalism. So, to be a person living in this world, if you’re a literate person, you can’t help but to have been influenced by “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood. One thing I tried to do in the book is, since I’m also writing about the rise of fundamentalism, I tried to make sure I wasn’t doing the same things that Atwood had done, to make it a very different take on it.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

What’s next for you? Do you have a new book that you’re working on?

I always have three or four projects going at the same time. So I’m working on a murder mystery, which I’ve always wanted to write. I’m working on a book set in the early 1900s that’s somewhat of a family story about a relative of mine who was sent to an asylum, because he was a gay man in a time when that just was not possible for him to be in that time and place. I’m working on trying to put together a collection of short stories. And I’m working on a play.

I feel, especially now in the times we live in, having a new project is always a way to keep hope going too. Always have something.

Exactly. I think that’s absolutely true. You can’t write a novel without being hopeful, because, at least if you write the way I do, you’re in it for years, so you have to have some hope of going forward.

Read more

about this topic