My father, the Rorschach test: My mother and I couldn’t see the same man, in life or in death

“I think Daddy did something to himself to get away from me,” my mother said.

Three years after my father’s death, my mother was focusing on what she believed was a white stain on the brown rug in his home office, where he died. She thought it had something to do with whatever he’d done to hasten his demise. Gentle attempts I made to tell her that wasn’t the case proved fruitless. So on a visit, I went into the office with her.

“Look, Mom,” I said, leaning down, rubbing my hand on the threadbare area, which she’d mistaken for a stain. “It’s just worn out.” I looked up at her. “From the wheels on his office chair.” I rolled the chair back and forth. “See?”

She wasn’t buying it. “Well, that’s what you think,” she said, as if to indulge me. “I think something else.”

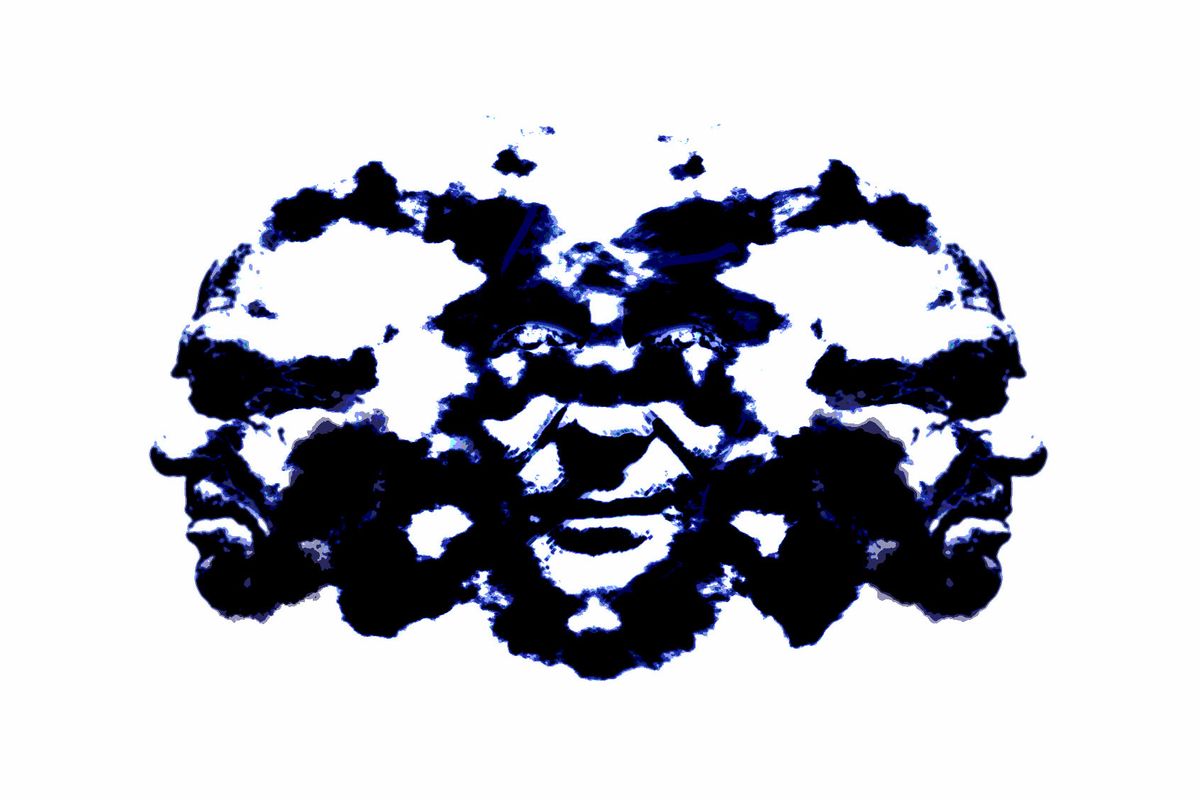

That’s how it was with us when it came to my father. He was our Rorschach test. My mother saw a self-sacrificing savior. I saw a self-serving aggressor. She saw a suicide. I saw a heart attack.

The stain may have been caused by bleach, my mother thought. Or maybe it was ground-up pills. She didn’t offer many details of her theory, and I didn’t push. “You know how smart he was, how much he read,” she said. “He could have figured something out.”

My father died the night before Labor Day in 2019. I went back to my childhood home with a suitcase full of every black dress I owned and whatever else I thought I might need for the next week, month, year, or forever. In the end, it was five weeks, the longest my mother and I had been together since I left for college 25 years earlier.

“I live here now,” I said on the phone to friends during those weeks. It was a joke, and maybe also a prayer. My father and I had been adversaries, rivaling for my mother’s affection. We had grabbed her back and forth from each other over the years. Now, finally, she was mine again. It was hard to let go.

But I had a job from which I had taken family medical leave, a husband and a nine-year-old son. My home was in New Jersey and my mother lived in Massachusetts, a four-hour drive away. Over the past 45 years, she had been diagnosed first with major depression and then with bipolar disorder. Lately, she had developed mild cognitive impairment, most likely caused by over 60 rounds of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), begun seven years earlier, to treat her depression when no medication would work.

This was part of my mother’s theory, that my father killed himself to get away from the relentlessness of her depression. “He hated driving me to all those ECT treatments,” she told me. But that wasn’t true. Taking care of my mother was the cornerstone of my father’s identity. It made him both the hero and the victim at the same time. As a child, he had just been the victim.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

No one ever told me my father had been sexually abused as a little boy by an older male cousin, but as a teenager I heard him hurl the information at my mother when they were arguing over who had it worse. I think it angered her, his being so vulnerable. That was her role. Their relationship was like an Escher drawing with his need to care for her twisting around her need to be cared for, in an endless loop that defied logic. No way in. No way out.

This was part of my mother’s theory, that my father killed himself to get away from the relentlessness of her depression.

In the weeks my mother and I spent together, I was alarmed to realize she no longer knew how to use a credit card at the grocery store, open the front door to the house with a key or turn on the TV. She hadn’t driven in years. So I found 24-hour care, and used the money my father left behind to pay for it. I filled a notebook with everything I could think of: names and phone numbers for her friends and family members and doctors and favorite stores and what she liked to eat for dinner. I left a note on her bed saying our time together had been magical. Then I got into a cab to take me to the train station, with the promise that I’d be back in a week for a visit. My mother stood on the front stairs beside the woman who would move into my room and take my job as her caretaker. They both waved.

For the first time in many years, I regretted leaving. Usually, all I felt was relief.

The bad visits home after I left for college had all collapsed into each other, like folds in an accordion. All I could see clearly were the ones at either end. On my first return home, I didn’t spend as much time with my mother as she thought I would. The day I was set to leave, she sat on the couch, catatonic, unwilling to speak to me or even look in my direction. “You broke your mother’s heart,” my father said. He may as well have said: I won.

This is one reason I knew my father didn’t kill himself. To do so would have been to give her back to me. And he never would have done that.

The last time I saw them together, about a month before my father died, we went out to eat with my husband and son. My father was impatient and cutting. His face was an enraged mask. He pulled my mother along when she walked more slowly than he did, was exasperated when she took too long to order, then was disparaging of what she did order. Meanwhile, my mother was like a turtle near a predator, head pulled into her shell. She used to defend herself. “Is there a nicer way you might say that?” she would ask. But not anymore. After dinner, back at their house, I beckoned my mother down the hall to my childhood bedroom, increasing my father’s fury. The only thing he seemed to hate more than being with her was being without her. I closed my door and whispered, “If you want to leave, I will help you.”

She looked at me like I was insane. “Of course not,” she said. “Daddy takes care of me.”

“Never ask for what you want,” was the first rule of our family.

Seeing them bring out the worst in each other was more than I could bear. I loved my father, who could be as kind as he was harsh. He held my hand when I was in labor. He carried my antique steamer trunk up four flights of stairs when I moved to New York City on my 23rd birthday. He supplemented my income so I could work in publishing, at a job that paid $7,000 less than what one year of my private liberal arts education had cost.

I imagined the abuse he suffered as a child made it terrifying for my father to engage in a true partnership with my mother. He always had to be in control, for fear of what happened when he wasn’t. But like so much else between them, it went unexamined. I wanted relationships with my parents independent of one another. But they were unwilling to spend any time apart. So in the end, I called once a week, visited less and less. I know they counted the number of days per year they saw me. It was their bitterness math.

Of course, it was not overt. Better they had said, “It’s nearly June and we’ve only seen you two days since January.” “Never ask for what you want,” was the first rule of our family. If you have to ask, the thinking went, the person from whom you wanted something never really loved you anyway.

My mother most wanted my father’s time. She described her life with him like this, “Out early. Home late. And meetings.” They met in college, both twins who were set up by friends. My father was tall and smart and Jewish, and my mother couldn’t believe her good fortune when he gave her his fraternity pin after they’d been together for a year. “What could he possibly see in me?” she asked her sister. It was a question she never stopped asking.

For her, his death is just another abandonment. But a heart attack is random. A suicide is personal. A suicide centers my mother in his death in a way she never felt centered in his life. Every suicide is also a murder, they say. A suicide says: You didn’t only do this to yourself. You did it to me, too.

My father didn’t kill himself. There was no evidence of self-harm, no note. He had a mild cardiac condition. He died of a cardiac arrest. It was written on the death certificate. It was the truth. But it wasn’t my mother’s truth, so it came up again and again when we talked, and we talked every night. Without my father there to undermine her, she was better than she has been in decades, having scaled down from 24-hour care to no care at all. No more ECT, either. She drove, volunteered, made art, did her own shopping and cooking.

“If only he had waited a little longer,” my mother said. “So he could see me now.”

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 (TALK), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

Read more

essays about complicated families: