I can’t forget — but I can’t remember what: Trump, the pandemic and memory

Just before Memorial Day, the Washington Post published a largely factual front-page report on the intractable nature of the COVID pandemic, now in its fourth or fifth wave — really, who’s counting? — as we head into another bewildering summer. Perhaps the article’s central theme is that everything felt different a year ago, “with predictions of a ‘hot vax summer’ uninhibited by covid concerns” and the virus “on the brink of defeat as cases plummeted to their lowest levels since spring 2020 and vaccines became widely available for adults.”

Even setting aside my grumpy complaints about easy-breezy, overly fatuous newspaper prose, that kind of threw me for a loop, and at first I had trouble figuring out why. I’m confident that I never thought the summer of 2021 would be an endless Katy Perry video, and I would have been tempted to fire anyone at Salon who employed the phrase “hot vax summer.” But it’s not just that: I don’t dispute that in some vague and general journalistic sense, the statement is true.

After sitting with the article for a minute, I worked my way backward to memories of being vaccinated in April of last year at a small-town pharmacy in upstate New York, and being on vacation with my kids on Cape Ann on the day in June when Massachusetts lifted its statewide mask mandate. Even in the nosebleed-expensive, woman-owned organic food market, everybody took them off immediately. We went to a crowded, boozy Mexican restaurant that night and literally nobody was wearing masks. So, yeah: Hot vax summer!

RELATED: Did you lose touch with a pre-pandemic acquaintance? You’re not alone

But here’s the thing: It took significant effort to dig up those memories and pin them to dates on the calendar, and even so it felt like I was doing research about events in someone else’s life, or things that happened in a movie I’d seen once — but could be mixing up with another one? They feel less like normal human memories than like fading family photos in a water-damaged album in the attic, or like the notes the guy in Christopher Nolan’s film “Memento” scribbles on his arm in a vain attempt to keep track of reality.

How much do I actually remember about last summer, or last Christmas, or the one before that, or pretty much any of the seasonal changes or major holidays of the last two-plus years? It’s not that nothing has happened: Far too much has happened, but for me — and I strongly suspect I’m not alone here — memory and cognition and the passage of time have been fundamentally disordered. I can remember things, but not as part of a consistent temporal narrative, and not attached to any sense of growth or change or development. It’s a bit like a brain-damaged version of the hallucinogenic top-down view of time attributed to God in classical Christian theology, in which past, present and future all occur simultaneously. (No wonder He acts like an asshole so much of the time.)

For me — and I suspect I’m not alone — memory and the passage of time feel fundamentally disordered. I can remember things, but not as part of a consistent narrative, and not attached to any sense of growth or change.

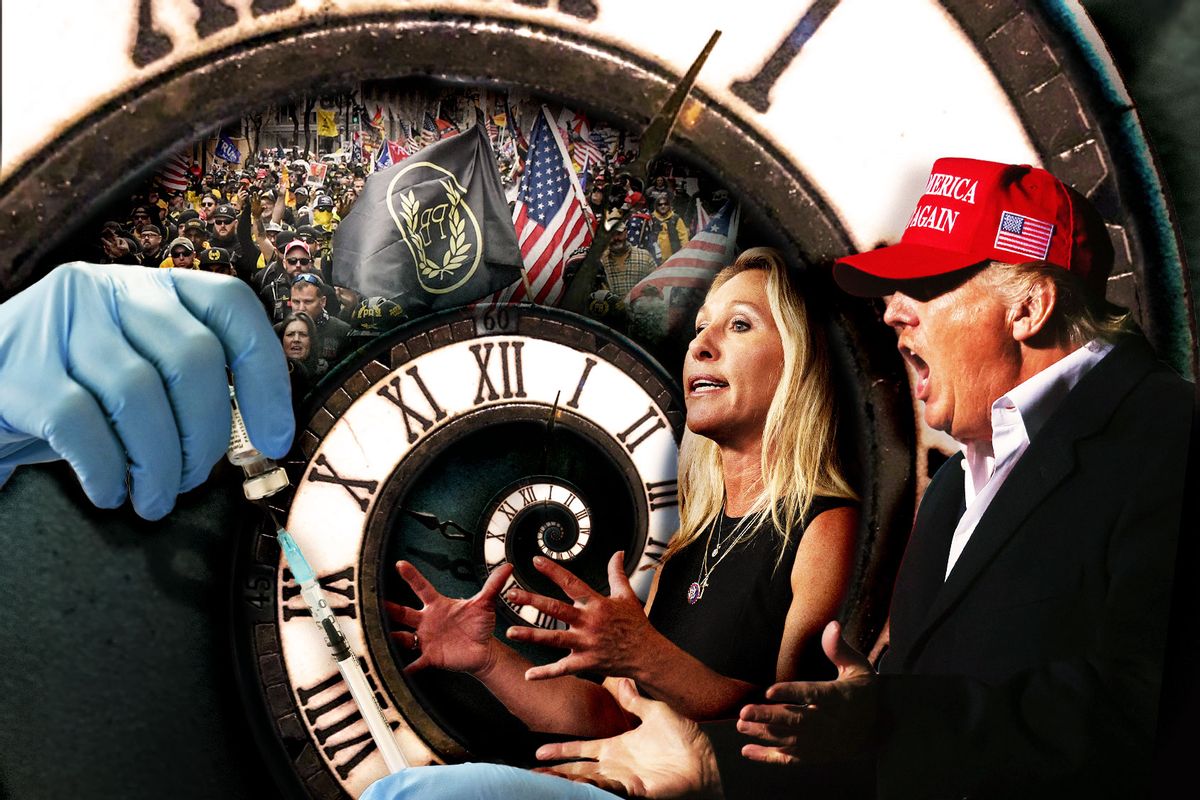

This is because of the pandemic, of course, and because of the lockdowns and social isolation and masking and overall anxiety. It’s also because of a lot of other stuff, including a new political and cultural split in our already hopelessly divided society, driven by an emerging and empowered coalition of anti-science and anti-government dissidents who have been drawn out from under the rocks scattered across our ideological landscape. If I woke up with my memory wiped, like the Guy Pearce character in “Memento,” and read a bunch of notes on my arm about Marjorie Taylor Greene and WWG1WGA and Aaron Rodgers “doing his own research” and the Jan. 6 insurrection and a president who thought the Chinese had a “hurricane gun” and the sub-“Fargo” plot to kidnap Gretchen Whitmer, I would conclude that none of it was true and I was a paranoid schizophrenic.

There’s another aspect of that dislocation and disorientation that’s difficult to talk about clearly, especially for those of us in the supposedly enlightened left-liberal quadrant of American society, with our plug-in hybrids and our elaborate cocktails and our charmingly “reclaimed” urban neighborhoods and our tiptoeing-on-eggshells approach to every aspect of language and thought. We don’t agree with the Trumpers or the anti-vaxxers or the Big Lie purveyors or the Great Replacers on any substantive questions, of course, but we understand where they’re coming from a little better than we wish we did.

It’s possible that I’m just speaking for myself here, but I bet I’m not. The sense of disempowerment and disenfranchisement that has driven Trump’s voters and Tucker Carlson’s viewers to embrace conspiracy narratives in which they are simultaneously victims and heroes is not imaginary, even if their solutions — somewhere between knockoff Ayn Rand fantasy and Franco’s Spain circa 1955 — definitely are. Consumerism, worsening inequality, cultural and geographical “sorting,” mental health and addiction crises and an increasingly corrupt and undemocratic political system, all of it juiced up by two years of pandemic and the flaming bag of dogshit left on America’s front porch by Donald Trump, have produced something close to a state of national psychosis.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

If you claim you don’t feel that and don’t understand it, if you insist that you and the people you know still believe in science and democracy and rational discourse and literary fiction that addresses the Big Questions, and that all we need to do now is buckle down and work to save the (so-called) Democratic majority in November — well, I’m verging on being mean but you get the point. There was no massive election fraud in 2020 and the COVID vaccines are not part of a totalitarian power grab. But I’m honestly not sure that the naive faith still cherished by many vote-blue normies that someday soon the Trumpian fever will fade and we’ll get back to what I once heard Jeb Bush — in the snows of New Hampshire in 2016! — call “regular-order democracy” is any less delusional.

One aspect of our collective loss of memory, then, is that none of us can actually remember the era when America was “great” or politics was “normal.” Because when was that, exactly? I’m getting pretty damn old at this point, but JFK was assassinated when I was a baby, and by the time I could read, American soldiers were burning down villages in Vietnam. The various visions of the paradisiacal American past remind me of Joan Didion’s line about how every Californian knows exactly when the state went to shit: a year after they moved there.

The New York Times recently surveyed a bunch of school counselors across the country who reported that many of their students were “frozen, socially and emotionally, at the age they were when the pandemic started.” Jennifer Fine, a counselor in Chicago, told the Times, “Something that we continuously come back to is that our ninth graders were sixth graders the last time they had a normative, uninterrupted school year.” As the father of two teenagers, that hit me right in the solar plexus. But while the phenomenon being described is undoubtedly more acute for children and adolescents, I think it’s a lot more general than that.

I don’t enjoy writing about myself in a personal or non-performative way, but I think the last thing to say here is that our understanding of time and memory has been disordered by grief and loss, and for me that aspect of the pandemic will never be abstract or “political.” Five people I knew personally died during the pandemic, including my mother, my aunt and one of my oldest friends. Another friend, a journalist several years younger than me, spent two months in the hospital with an infection of the “mild” omicron variant.

I have not been able to mourn any of those deaths properly. That’s my problem, and no doubt reflects my personal pathologies, but it is not my problem alone.

I have not been able to mourn any of those people properly, or to think clearly about the larger context of their lives and my own. That’s my problem, and certainly reflects some of my specific pathologies, but it is not my problem alone. It connects me to the experience of millions of people around the world who have lost loved ones without what many of us regard (in our privileged Western bubbles, no doubt) as the usual rituals of farewell, mourning and closure. It’s a dreadful kind of sharing: shared loss, shared loneliness, the shared absence of something we cannot quite name.

I suspect that five is a relatively high number, considering my race and class and privilege and all that stuff. But I am also aware that a few miles south of where I live now, in the housing projects of the central Bronx where thousands of health care aides and transit workers and mail carriers and other “essential workers” live, knowing five people who died might be an average or low number. When I consider how much my life has been disordered and try to imagine that multiplied by the true scale of grief and loss and death in my city, in our nation or around the world — well, of course I can’t do that. Nobody can.

My mother — who was my best friend, my writing mentor and my model in all things, especially borderline-inappropriate humor — died the day before the presidential inauguration in January of 2021, which was pretty cruel: She had vowed to live long enough to outlast Trump, and would have enjoyed that moving day of celebration. I got up the next day as usual and turned on the TV, because it was obviously a historic moment and because it was my job, and cried through the whole thing. (I don’t remember crying on any other occasion in the last two and a half years, but as stated, my memory isn’t reliable.)

On the other hand, my mom didn’t have to watch the Biden presidency slowly collapse into despondency and chaos, which would have driven her crazy. And consider this: She left this world never having heard of Marjorie Taylor Greene, which strikes me as a tiny data point in favor of a merciful God.

I have written very little for publication during the pandemic years (as a handful of Salon readers have noticed, and thank you), and I suppose this article is a way of explaining, largely to myself, why that happened. I focused on where I could be functional, or at least where I could fake it: Running Salon’s political coverage, parenting two teenagers frozen in time. Both my kids have been depressed, isolated and confused; one of them suffered a life-altering injury (but not life-threatening, thank God) that has required one major surgery and will soon require another.

I moved twice, or maybe three times, depending on the definition of “moving.” I have completely lost track of a few supposedly important possessions, but others have resurfaced that I had forgotten about: My Irish grandfather’s dog tags from World War I; a scrapbook my mother made during a trip to Europe as a teenager, in which she drew a sketch of the Nazi flag flying from the stern of the luxury passenger ship that took her there. (The menus are amazing!)

A long-ago girlfriend sent me a photograph of her, on the street in London, and told me I had taken it. I looked at it without the faintest glimmer of recognition: “You and I were never in London.”

I tried at some point to begin a relationship, and all I can say to that person now (and to a number of other people in my life) is that I literally, not metaphorically, have no idea what I was thinking. One of the objects I found recently was a snapshot sent to me a few years ago by a different woman, someone I was involved with decades ago. She was throwing stuff away but thought I might like to have this picture I had once taken of her on a London street. I looked at it without the faintest glimmer of recognition: “Some other boyfriend,” I wrote back to her. “You and I never went to London.”

Yes we did, she reminded me, gently adding that she could understand why I didn’t remember. At the time, I was shocked to encounter such a noticeable gap in my supposedly excellent memory. I understand it better now.

When I look at that photograph today, I still don’t remember taking it, or being on that street at that moment with someone who was beautiful and kind. But I remember other things: The cat who lived in our B&B near Paddington Station, the creaky, uncomfortable bed we slept in, and then, a few days later, standing on a cliff in the west of Ireland with a group of beloved relatives (all of them dead now) and throwing my father’s ashes into the Atlantic Ocean. It almost feels like an invented scene, a literary scene. But I’m pretty sure I was there.

Read more on the long-term consequences of the pandemic: