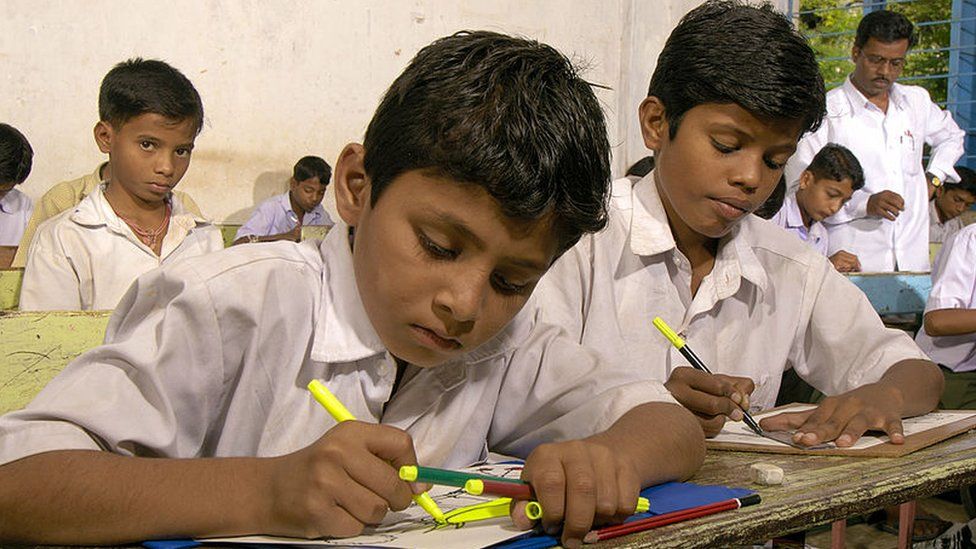

Why India’s poorest children are falling further behind

Ten-year old Laxmi may never return to school. When the first wave of Covid-19 hit India, in early 2020, her school closed its doors and now her parents can no longer afford to send her.

Laxmi was attending a nearby private school at a cost of £21 ($26) per year, which the family funded by borrowing from relatives.

They chose the school – which has since reopened – partly because they were worried she would not be safe travelling to the government-funded school in the next village.

Her parents also had concerns about the quality of teaching and the lack of toilet facilities at the public school.

“I have three daughters. Laxmi is the eldest. We had thought that life would be different for her, than us, after being educated.

“Even though my husband and I hardly make anything, I wanted my children not to have the same life as me,” says her mother, Rekha Saroj.

While the pandemic prompted a flurry of new online education platforms aimed at democratising education for Indian children, for the country’s most deprived households, these resources have simply not been accessible.

“Digitalisation of studies may be good but what about us? With no access to money, or the internet, how are we going to have a better future?,” says Mrs Saroj.

For children in government schools there are several schemes available to promote digital education, including DIKSHA an online service for schools which has content in 32 languages.

Although well-intentioned, these efforts appear to have had minimal impact for children while schools were closed during the pandemic. According to India’s Annual Status of Education Report (Aser), in 2021, only 40% of enrolled children had received any type of learning materials or activities from their school during the week of the report’s survey.

The situation was most acute for the youngest children, because they tended to have the least access to technology. The report says almost a third of five to eight-year-olds do not have access to a smartphone to help with their learning at home.

“The proportion of families who had some contact with teachers was heavily skewed towards better-off families,” the report noted.

“The [Indian education] system is largely designed for privileged children, the easy winners in this uneven race,” explains Jean Drèze is a Belgian-born, economist who focuses on India.

“Schools were closed for nearly two years – under pressure from well-off parents who were not so worried about the learning gap because their children were studying online at home.

“Children with no access to online education were more or less abandoned by the schooling system.” He says as India’s schools are now reopening, “much too little is being done to help children who have been left behind,” to redress the gap.

So what, if anything, could technology do to close this widening gulf?

Mihir Gupta is the co-founder of Teachmint, an online platform, where teachers can hold lessons, distribute material and message students.

The service reaches ten million teachers and students in 5,000 cities and towns, according to Mr Gupta.

He acknowledges however, the significant challenges of reaching students in poorer areas where internet connections may not be reliable.

“We realised early-on that internet bandwidth variation across different parts of India is a challenge to reach more and more educators,” he says. Consequently, Teachmint’s service has been optimised to work with slower internet connections and on mobile devices – rather than laptops and desktop computers.

Nevertheless, Anjela Taneja, who heads the Inequality Campaign for charity organisation, Oxfam India, says much more needs to be done urgently.

“Even in families [with] access to high-tech or low-tech tools, children struggled to learn remotely,” she says.

A “conducive environment” for learning at home can often be lacking she adds, with girls in particular suffering as they often take on household chores in addition to studying, while there is a “preference” to give boys gadgets.

The government says it is helping support rural areas with BharatNet, a scheme to give rural areas faster internet connections.

Through the scheme, which was launched in 2012, 52,567 government schools have been given broadband connections, a spokesperson for India’s Education Ministry told the BBC.

It also said that schools which are still waiting for a connection can use government-funded TV, radio services and a host of other education services.

Shiv Kumar works for Oxfam in deprived areas of Uttar Pradesh. His job is to try to get more children attending school regularly.

“It’s a saddening situation in Indian villages. It’s a challenge to convince parents to send their children to school,” he says.

Many of the households he visits lack either an internet connection, or a smartphone at home.

To help, he has started a something called a ‘mohalla’ class. Mr Kumar will visit a house and invite children to come along and give lessons to any who turn up.

He uses his smartphone to show the children the Hindi alphabet, numbers and other teaching aids.

This type of supplementary schooling is becoming more common in rural India and provides two to three hours of extra education a week but relies on the help of community volunteers.

“We are talking about digitalising education, but how is that possible for village parents who have a limited means of livelihood?” he asks.

There are many kids who feel left behind. Sixteen-year old Sivani, from Uttar Pradesh fears the window of opportunity for her may have closed. She finished schooling at the age of ten.

“I wanted to study but did not have the means to fulfil my dream,” she says. “My parents think working at home and taking care of the family is more important than getting educated.

“I am not the only one. Many girls in my village don’t study… how is life going to change if we don’t study?,” she asks.