That time a foreign-born socialist ran for mayor of New York

Maybe you’ve heard about the socialist candidate running for mayor of New York City. He’s an immigrant from a complicated ethnic background, and his opponents accuse him of being unpatriotic, anti-American, a Communist agent and a supporter of overseas terrorist movements. Some have suggested that electing him mayor will make antisemitic bigotry — already far too widespread in America — much worse, and is likely to fuel a vicious, jingoistic right-wing backlash.

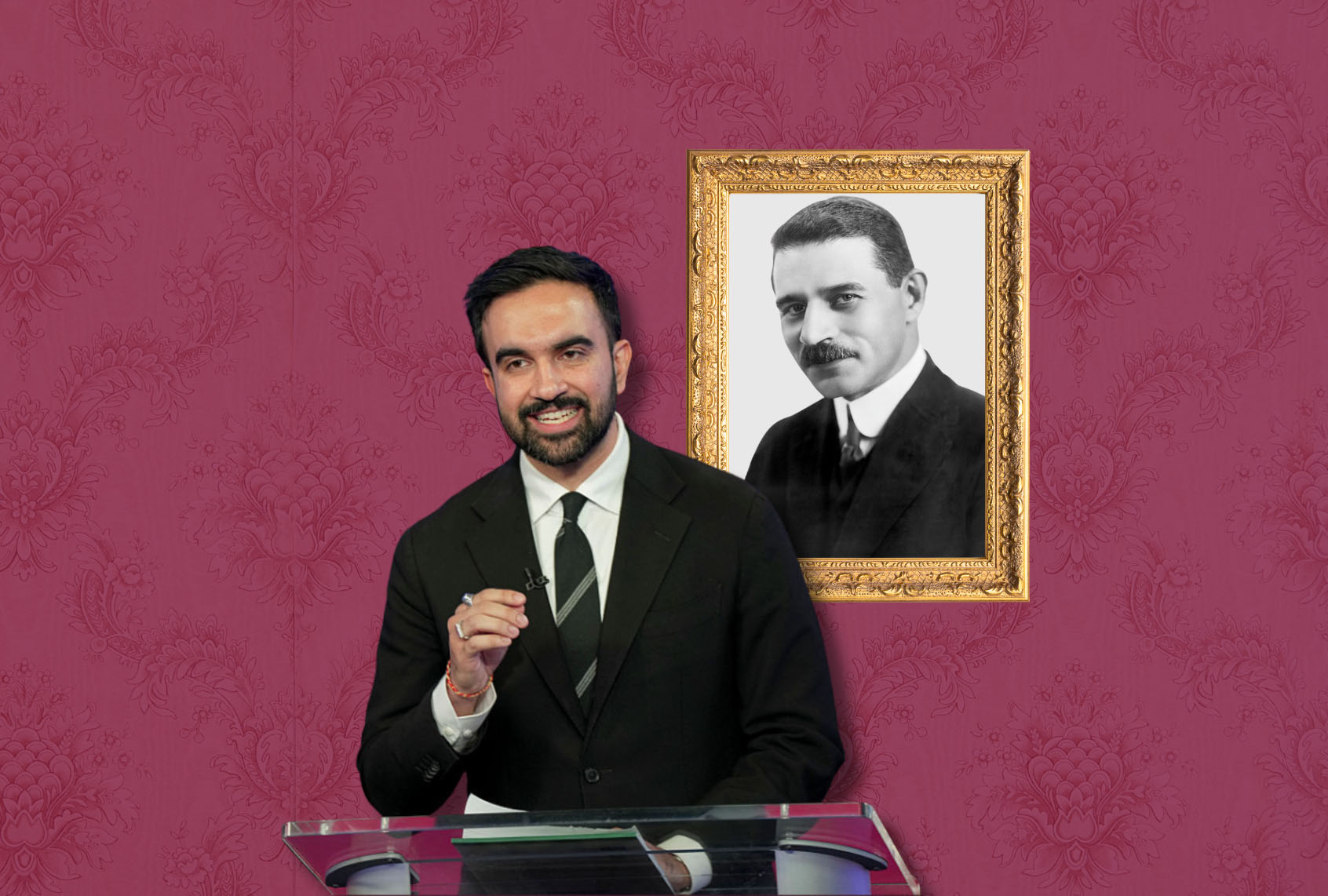

For his part, this insurgent socialist — an articulate and dynamic speaker, and a persistent critic of the Democratic Party’s hypocrisy and cowardice — insists that he represents the finest traditions of American patriotism, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence. His movement, he says, represents the enormous diversity of New York, a city endlessly renewed by immigrants from all over the world.

Most of his campaign hasn’t been about abstract issues of foreign policy or political ideology. Instead, he has remained focused on the real conditions of working people’s lives, and the rising cost of living in America’s most expensive city. He has promised to control rising rents, improve public transit and make groceries more affordable, perhaps by selling food directly to consumers through farmer’s markets and city-owned stores.

I’m talking about Morris Hillquit, the Socialist Party of America’s mayoral nominee in 1917. But you knew that, right?

If history often rhymes, as the familiar slogan holds, this time it rhymes like crazy. In structural and thematic terms — and even on a more personal and narrative level — Zohran Mamdani’s 2025 campaign is startlingly similar to Hillquit’s. Even those elements that might strike some observers as important differences are arguably more like parallels. Mamdani was born in Uganda to a Muslim family with South Asian roots; Hillquit was born in Latvia (part of the Russian Empire at the time) to a German-speaking Jewish family. In other words, both were outsiders from birth, and remained so in America, a fact that clearly forged their political identities as well.

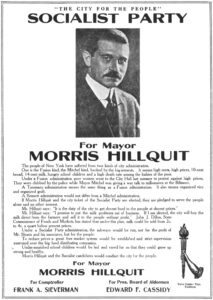

The similarities between their campaign themes — incumbent mayor John Purroy Mitchel, according to Hillquit, had brought New Yorkers “high rents, high prices, 10-cent bread, 14-cent milk” — points us toward the unsurprising conclusion that the fundamental problems of life in the capital of American capitalism haven’t changed much in the last 108 years. The proposed solutions offered by socialist reformers remain familiar as well. (Despite all the Red-baiting, both then and now, neither Hillquit nor Mamdani could remotely be described as a revolutionary.)

(Socialist Party of New York/Public domain via Wikimedia Commons) Hillquit campaign poster, 1917.

But the differences between the two men and their historical moments are just as important and, believe it or not, they offer reasons for optimism. If the political and ideological divisions that made Hillquit unelectable are still with us — yeah, he lost; let’s get the spoiler out of the way — the clear and present danger posed by Donald Trump’s authoritarian movement has changed the context dramatically. What we see here and now, in New York City and across America, is that the political machinery that crushed Hillquit and 20th-century socialism has broken down, and ordinary people are looking for more.

Hillquit may seem like a historical footnote today, but he was a well-known political figure in 1917. In the same year he ran for mayor, he also served as the defense lawyer for several left-leaning publications that Woodrow Wilson’s administration tried to ban or shut down, including the radical culture magazine The Masses, the nation’s two socialist daily newspapers (!) in New York and Milwaukee, and the Jewish Daily Forward (then published in Yiddish). If you’re experiencing an uncanny, reverse-déjà-vu sensation right now, I feel you.

In the same year he ran for mayor, Hillquit was also the defense lawyer for several left-leaning publications that Woodrow Wilson’s administration tried to ban or shut down. Experiencing reverse-déjà-vu yet?

After arriving in New York as a teenager, Hillquit — born in 1869 as Moishe or Moses Hillkowitz — became a prominent New York labor lawyer and then a co-founder, with Eugene V. Debs and Victor Berger, of the Socialist Party of America, a big-tent effort meant to unite a wide range of political opinion to the left of the overtly racist and blatantly corrupt Democratic Party.

If Hillquit’s mayoral campaign was close to a high-water mark for official American socialism, it was also the beginning of the end. Debs had received more than 900,000 votes in the 1912 presidential election — about 6 percent of the national total — and the SPA had elected two members of Congress and more than 1,000 local and state officials all over the country. While its greatest strength was among recent immigrants, it also prospered in what we would now call red or purple states: Kansas, Nebraska, Idaho, Oklahoma, Nevada, Arizona. Socialist mayors were elected, just for example, in Butte, Montana; Gulfport, Florida; Red Cloud, Nebraska; and Star City, West Virginia.

But by the time of Hillquit’s campaign, the American left was already bitterly divided over U.S. intervention in World War I, which Hillquit and most of the SPA strongly opposed. Socialists, anarchists, pacifists and other perceived radicals were also under tremendous stress from the aforementioned government campaign of persecution and censorship, including the infamous Espionage Act.

Over the next few years, those factors, along with the global ripple effects of the Russian Revolution, would split the Socialist Party into multiple warring factions. Hillquit remained loyal to the SPA until his death in 1933, but many of its more militant members joined the newly-hatched Communist Party USA, whose overt alignment with the Soviet Union meant that virtually all avowed socialists were exiled to the political margins for decades to come.

In case you’re wondering, there appears to be an almost-direct line of political descent from Hillquit to Mamdani: The last remnants of Hillquit’s SPA splintered into three offshoots in the 1970s, one of which eventually became the present-day Democratic Socialists of America, whose members include Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Rashida Tlaib and 200 or so other elected officials, along with the likely next mayor of New York.

There’s a connection: The last remnants of Hillquit’s Socialist Party split up in the 1970s, and one of its offshoots eventually became today’s Democratic Socialists of America, home to AOC, Rashida Tlaib and Mamdani.

Hillquit surely never expected to win the mayoral election, which may be the most significant difference between his campaign and Mamdani’s. After all, he was fighting the combined power of the Tammany Hall political machine and newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, who united behind John Francis Hylan, a vaguely populist Brooklyn Democrat with few discernible positions. (Hylan’s name now graces a nondescript boulevard in suburban Staten Island, while Hillquit is memorialized in a housing project for union members on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Both seem fitting.)

Hillquit ran a strong campaign under the unique conditions of that world-historical year, by all accounts, winning almost 150,000 votes across a fractious range of communities who were generally understood to be at odds. It’s not surprising that Jewish socialists and much of the labor movement were behind him, and also not surprising that Manhattan’s “Uptown Jews,” a term then used to indicate the affluent, assimilated Jewish community of long standing, viewed him as a dangerous interloper who threatened their safety. Black voters were largely ignored or bought off with low-level patronage jobs in the Tammany era, but future civil rights hero A. Philip Randolph organized for Hillquit in Harlem, winning him about one-fifth of the African-American vote.

Less plausibly still, Hillquit made modest inroads into New York’s other dominant ethnic community of the time. I first encountered his name, in fact, in a 1970s biography of the Irish revolutionary Liam Mellows by Marxist historian Desmond Greaves, who mentions Hillquit several times without bothering to explain who he was. Ireland and Irish issues are never mentioned in Hillquit’s online archive or his (largely hostile) Wikipedia entry. Greaves reports, however, that he was friendly with Irish republicans like Mellows (then living in New York exile), and was backed by the Irish Progressive League and the Irish World, a socialist (and vigorously anti-British) newspaper.

Given that the Tammany-backed Hylan and incumbent mayor Mitchel were both of Irish ancestry, it’s not likely that Hillquit got an objectively large number of Irish-American votes. But the point Greaves makes is that the Irish in America faced a moral and political choice in 1917 — effectively, a choice between anti-imperialism and cross-ethnic solidarity on one hand and “Americanism” on the other — that would determine their future. By extension, the Jewish community, the Black community and the American left at large faced their own versions of that choice. I would argue it’s still with us today, and still urgent: Consider the spineless vacillation of Hakeem Jeffries and Chuck Schumer over whether to stand behind their own party’s mayoral nominee in their own city.

Want more sharp takes on politics? Sign up for our free newsletter, Standing Room Only by Amanda Marcotte, now also a weekly show on YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

In the political hothouse atmosphere of 1917, there was a stark dividing line: You could stand on your principles — socialism, internationalism and anti-imperialism, for example — and suffer the consequences, or you could swallow the kind of unquestioning patriotism that accepted the carnage of the Great War in Europe as noble or at least unavoidable. Hillquit wrote about that kind of patriotism, calling it a “very much abused term”:

In this campaign the country is infested with a swarm of professional patriots, including men who are aspiring to the highest office in the land, men who have occupied the most exalted positions in the gift of the nation and other great national luminaries. They travel throughout the country prating about “true Americanism,” they wave the American flag with rivaling frenzy, they flatter our national vanity, they appeal to our basest instincts, they foment racial antagonism at home and pave the ground for strife and war with foreign nations. Their agitation is harmful to the people, it is grossly unpatriotic.

Is he describing the warmongering of 1917, or the Charlie Kirk memorial of 2025? I’m not quite sure.

For many groups of people over many decades, the sacrifices and compromises required to be seen as fully “American” seemed to be worth it. The Irish had nearly completed that process by Hillquit’s time, and his own community was about halfway there. For Black people in America, it’s safe to say that progress has been painful, intermittent and slow. Wasn’t the basic premise behind that sacrifice that what it meant to be American was not a fixed quantity, and would continue to evolve and expand? That certainly seemed to be happening, for a while. Now it’s very much in question.

Morris Hillquit lost the 1917 mayoral election, and never came close to political power again. He was decidedly a moderate within the socialist movement, not a revolutionary or an uncompromising radical, which may be why he has almost entirely vanished from history. But he fought for cheaper milk and better subway service, and refused to abandon his convictions for short-term political advantage.

Whether or not Zohran Mamdani has ever heard of Hillquit, he should be proud of inheriting his century-old legacy. Hillquit would have understood the importance of this moment, when too many Americans are once again ready to crumble before the most toxic forms of patriotism. What Mamdani’s surprising campaign — and his likely victory — have shown us is that we still have moral choices to make, and that courage isn’t just for losers.

Read more

from Andrew O’Hehir