Danzy Senna Reveals the Cover of Her Next Novel, Colored Television

Danzy Senna’s Colored Television—one of the most absorbing, darkly comedic novels I’ve had the pleasure of reading in recent months—operates as something of a “cracked mirror,” or so argues the author herself. “There is something really transgressive about comedy,” she tells me when we meet over Zoom. “It does a lot of work, in terms of undermining sacred things and showing us what’s absurd about the culture we’re living in. It changes people’s psyche to have that experience of laughter.”

And Colored Television is indeed hilarious, if you can balance its humor on your tongue with the mingling taste of melancholy that defines its protagonist, Jane, a biracial novelist bent on writing the “mulatto War and Peace”—only to discover her manuscript is completely unsellable. Desperate to lift her family out of an increasingly unstable middle class, she turns to the cash flow of Hollywood, and specifically to a larger-than-life producer who’s convinced they can create the “prestige” “Jackie Robinson of biracial comedies.” A game of representation bingo ensues, pitting Jane against her artist husband and, perhaps, against herself.

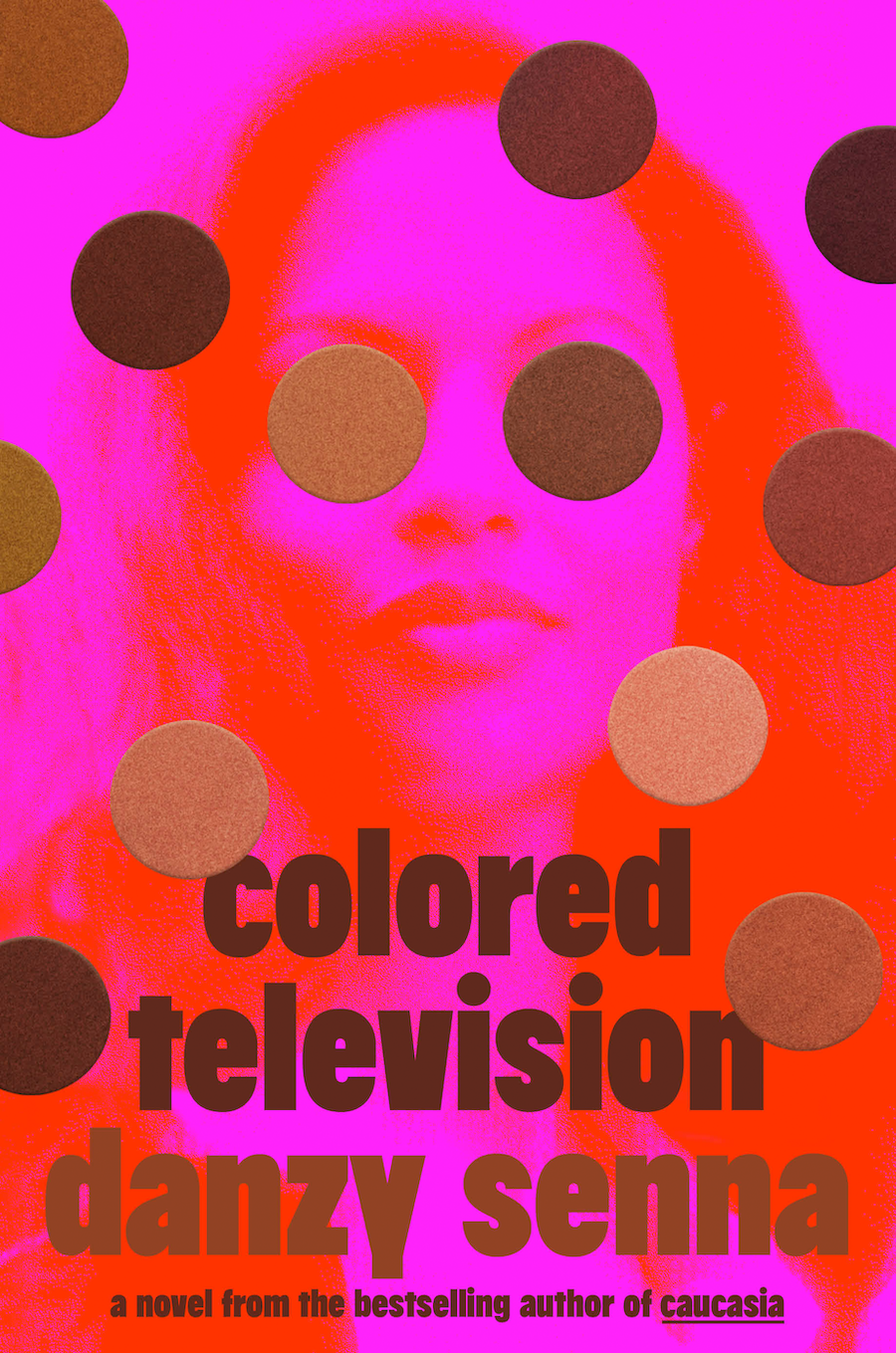

Ahead of Colored Television’s release on July 30, ELLE.com is exclusively revealing the book’s cover, designed by Lauren Peters-Collaer. Below, a conversation with Senna about how the book first began; why she employs humor as a means of transformation; and how Hollywood—and writing about Hollywood—shifted her perspective on literature today.

Let’s start with this: Where did Colored Television come from? What was the inciting incident, when you knew you wanted to write it, or even what it was?

I’ve been wanting to write a Hollywood novel for a really long time. I’ve been in L.A. now for almost 18 years, being a novelist. At some point in [Colored Television], someone says that [being a novelist in L.A.] is like being an Amish person because you’re writing for the page and everything around you is for the screen. Prestige television has, in some ways, become the novel of our time, in terms of what people are talking about and its influence. You do, sort of, start to have an identity crisis as a writer of fiction. What is the value of books in a culture that doesn’t have the same attention span?

It was like a creative crisis I was going through at the time—thinking about all of these stories I’d been writing for so many years. Since the early ’90s, really, I’ve been publishing work and feeling the bewilderment of the audience at what I’m doing, and seeing this other industry behind me, this glittering giant exciting world of film and television. And then trying to have faith in the lonely project of writing the work I was doing, and writing from a very specific point of view.

In the midst of that crisis, when did you decide, I’m actually going to make a book out of this?

I’m always trying to write my own experience into existence, since I started to become a writer. I was really interested in this family [in Colored Television], one that I exist in but that isn’t [my family], but it resembles us in certain ways. It’s Black and biracial creative writers and their quirky children, and the sense of: You’re doing this work, and it’s not really making you wealthy at all. It’s this labor of love. So I think I just started writing this character and this family and this landscape of Los Angeles.

One of the issues I was interested in—when you’re talking about an inciting incident—was this feeling, when you’re a writer of color, of scarcity: that there’s only going to be one spot given to, in this case, the mulatto story on television. I thought it was funny and sad, the idea of all these people competing for that one spot, to be the one to represent this identity. How it sets you up to feel like an imposter no matter what you do. I was really interested in all of those dilemmas for the person who’s trying to write from that outside-of-the-main point of view, and what that sets up amongst us as a people.

What was the timeline, in terms of when you started and when you finished?

Oh my God, it was so messy and ugly. The crazy thing is, I actually started this right before the pandemic. We were living temporarily in a nursing home, the whole family, and that comes into the novel.

We were doing a temporary thing while we were about to move into our house, and so I started it there. Us working on our novels in this nursing home with our kids and our dogs and…everything about it was so absurd. I started [the book], then we moved out of this nursing home into our house, and then suddenly there was the pandemic. And I have two kids who are now teenagers; the book really had to be put into a drawer and I had to deal with their feelings of being at home for two years locked in the house. So I spent a year and a half away from the book while I was managing them and managing our lives. And then when things started to open up, I pulled it out again and had to reacquaint myself with it. So for a couple of years, I’ve been taking those initial 100 pages and turning them into the novel that I now have.

Was the experience of writing this book different for you, in comparison to the work you’ve published before? Did it materialize in a different way than you’d perhaps expected?

I think I felt a lot more free with this book. I’m a mixed-race writer who’s been writing about characters of mixed race since I began writing. But I’ve had so many strange moments along the way of people saying, “Why do you keep writing mixed-race characters? Why are your characters so obsessed with race?”

I’ve been writing since, sort of, the dark ages in a way—because there was no representation of anyone like me when I started writing, and certainly no positive representation. Usually, it was seen as this tragedy if you were of mixed race, but also that there was only one story: You are supposed to have this one thing you tell, and then either you move on and write about other stuff or… There’s a weird projection onto you if you’re a writer of this specific background. So, for me, one of the things I’ve grown into is realizing that I am perfectly comfortable writing from that perspective as much as I want. That’s the universal perspective for me.

Also, I think I had more confidence: I love humor, I love comedy, and comedy, for me, is my happy space, in terms of how much it holds anger; it holds sadness; it holds all these other emotions within it. All the writers I love most have a cracked sense of humor. I think this [book] was me allowing that voice to really roam free and be like, I’m going to do a send-up of everything that you hold sacred, and I’m not going to apologize or hem that in. I’m going to let this book be as absurdist as I want it to be because that felt most truthful to me.

What is it about comedy that you find to be such an apt tool for your work? One you repeatedly reach for?

There’s a lot of power in comedy. You disarm people… I don’t want them to be thinking about the subject, or to think of it as work or medicine they’re taking, because a lot of the things I’m joking about are to do with race and identity and gender and politics and motherhood. And I think, for a woman, [comedy] is really a powerful tool because we’re not expected to have that level of irony and multiple meanings in our work. And especially as a woman of color, you’re supposed to be writing, essentially, memoir that’s sentimental. You are the specimen, and we’re looking at your sad life, especially if you’re mixed-race.

I think there’s a lot of power in shifting the gaze around and saying, Actually, I’m looking at you. You’re not looking at me. I love flipping the expectation of the reader that they’re reading about a certain subject, and yet they’re destabilized by the fact that it’s funny. Something that you think, Okay, we’re not supposed to be laughing at this, but the fact that we’re laughing at it means that we’ve actually survived it.

Let’s talk about the cover: When you were working on this book, did you have an idea of what you hoped it might look like on a shelf?

I am not really a very visual person. I’m terrible at creating a space, but I also have really strong opinions of what I like and I don’t like. So with this book, I did try to send [the art department] a mood board—because I had certain paintings that I love, and visual artists. I even had television show stills and stuff in my head that were really interesting to me. I said, “I don’t know what the cover should be, but this is the mood I’m coming from.”

They brought me one cover that was really great, but there was no human being in it. It was just a landscape. And I felt like the title is so, kind of, cold—I like the cold title, but I felt it could almost sound like a nonfiction book if it’s not clear that it’s about a character and colored television as a metaphor. I was like, “That’s great for the first cover I’m seeing, but let me just see one with a person.” And so then they sent me this, and I immediately responded to it. I loved it.

You said something interesting when we first started chatting: Part of your pursuit in writing this book was to address some of your own feelings about the state of literature, the state of Hollywood, and of culture in general. How did this book impact, reinforce, or undermine those feelings?

I also do write for screen. So I’ve slipped into both writing for television and film and then also doing fiction. I think doing both of them has made me value both things. But I think I see that there’s this space you hold as a fiction writer, where you’re alone in a room trying to create something out of nothing. When you make a movie, there’s a director, there’s a designer, there’s actors. When you’re writing fiction, you’re actually all of those things. It’s much harder work, in a lot of ways. I also find, as an artist, there’s something I’m nourished by, in terms of language and sentences where it’s all mine and it’s a very singular vision; whereas the other, the collaborative, has other possibilities.

I think I come to fall back in love with fiction and books and the act of writing alone in a room. Even the reading of a novel, for me, is a more whole-body experience than watching something on screen, because I have to do all of the work as the reader as well. When you’re reading, you’re also the director; you’re the casting person. So you’re, in a way, more invested in the story when you have to do all that work in your head. I think I’ve come back around to feeling like this book healed my feelings about being a fiction writer and seeing its value in the world as someone who makes books.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Lauren Puckett-Pope is a staff culture writer at ELLE, where she primarily covers film, television and books. She was previously an associate editor at ELLE.