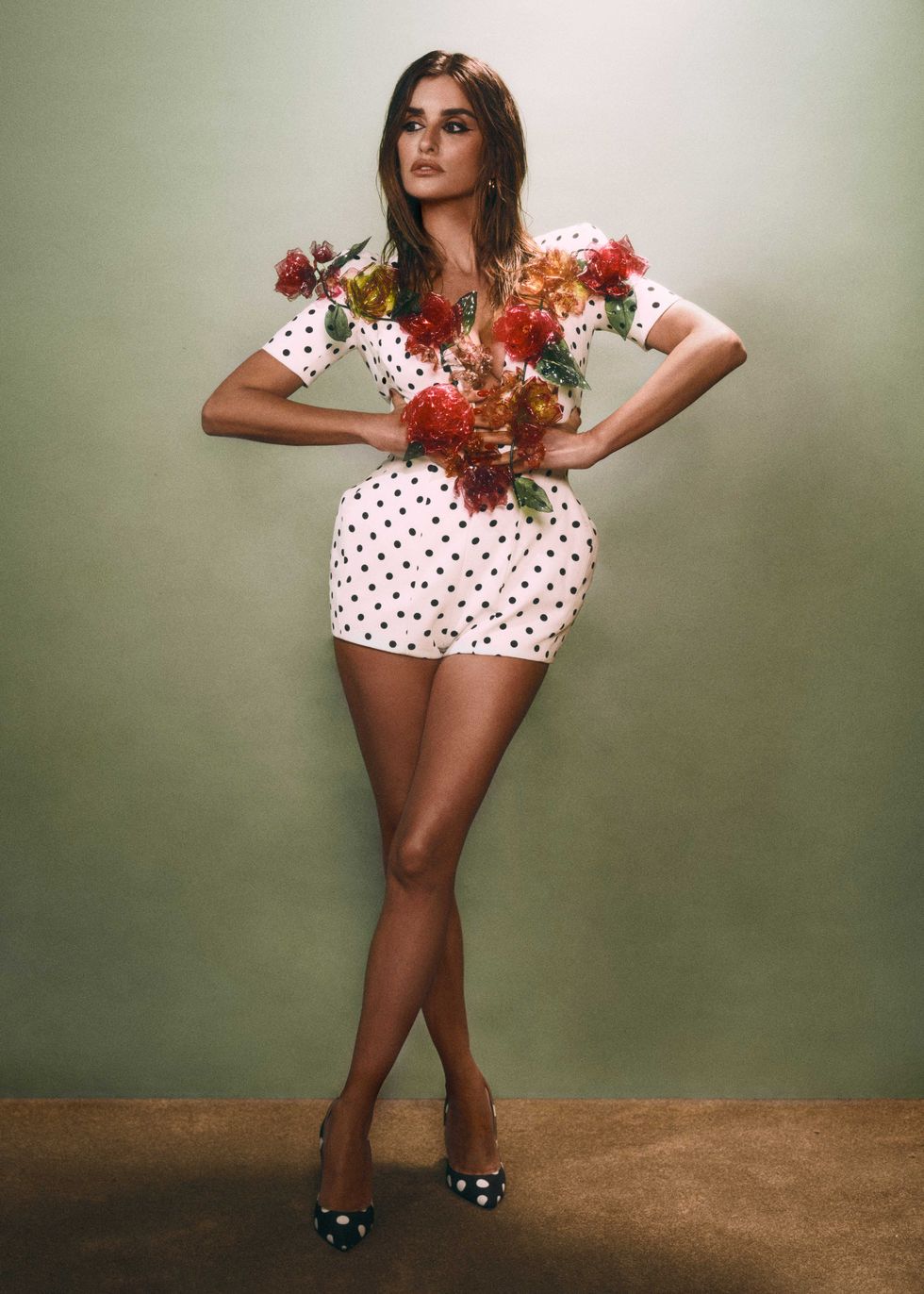

The Compassion of Penélope Cruz

Penélope Cruz would like nothing more than to feed me ham. So much so that these are her first words when I meet her at her production company, 30 minutes north of Madrid: “Hello. Nice to meet you. Ham?” Her iconic accent, so enticing to Americans she could have a robust side career in sleep stories, turns the word to “hum.” I had not factored in this scenario, three decades ago, when I decided to give up meat. “Oh, well,” she says, eyes on her office door, pulling out a chair. “Ham is coming in about 20 minutes.” The 49-year-old Academy Award-winning star of countless films (well, IMDb can count them, but even the most avowed Cruzphile would have trouble rattling them off), including All About My Mother, Volver, Vicky Cristina Barcelona, Parallel Mothers, and Vanilla Sky (twice, if you include Open Your Eyes) is disarmingly easygoing. True, this combination of mystique and personability is well-calibrated. She’ll be the first to admit that “I’m programmed to protect myself,” but it can’t possibly have any bearing on her fly being open.

“Ah,” she says, looking down past her chunky pink Chanel sweater and belt, buttoning her jeans. “Always, always, I don’t know the answer to that. I don’t do it on purpose.”

Cruz’s warm demeanor—she’s a natural comic, her smile takes up a greedy amount of real estate on her face, and she speaks with real tenderness about the last time she saw Karl Lagerfeld, when he convinced her to take a late-night stroll through Central Park—exists in sharp contrast to her latest role of Laura Ferrari, the hardened wife of Enzo Ferrari (played by Adam Driver) in Michael Mann’s breakneck biopic Ferrari.

This is at once a departure and a return to form for Cruz. It’s not her first time playing a biographical figure and certainly not her first “homage to a woman in a difficult situation.” She embodied her friend Donatella Versace in The Assassination of Gianni Versace: American Crime Story. But Laura is different. For one thing, she is not an internationally recognized name, so Cruz felt the weight of “giving her a voice for the first time.” For another, she arrives on screen bereaved, already grieving the loss of her son. “Every day is a question of how she makes it through the day. She has this tragedy that she will never recover from, and it’s also what made their marriage break because they both feel they failed to save him.”

One can sense the depth of Cruz’s research as a battery of emotions make their way across her face in Ferrari’s early scenes. “I found all these letters between them, these real love letters where, even after everything was deteriorating for them as a couple, the love and respect was very strong, even if later there was a lot of betrayal. They built this company together. When we were filming in Modena, there’s so much other people didn’t know. Or didn’t want to know. I went to the factory and met people who knew Laura, and it’s like they didn’t want to mention how much power she had. You know she slept with the tires? The night before races, she would sleep with the tires so that no one would sabotage them. But people would say no, no, she was a difficult woman. Very sour and unpredictable. Some called her crazy. The word that has been used for every woman in history to justify suppression.”

Laura is relatively subdued for a Cruz character (relatively…in one scene she waves a gun). Even her clothing is muted (“the sorrow has to be reflected every morning when she gets dressed, even when she opens her closet”), making the film a photonegative of Cruz’s films with Pedro Almodóvar. Those are worlds built on primary colors. In Ferrari, the paneling is dark wood, the suits are gray, and the only pop of red is the cars. None of which Cruz would be caught dead driving.

“I have a fear of driving,” she says, which explains why we are staring out the window of her office and not in a Ferrari Spider, my suggested locale for our meeting. “My sister was run over by a car in front of me when I was eight or nine. I remember she was wearing a red coat. Speaking of red! And for me, time stopped. It’s a great trauma, because I saw her losing consciousness. And I was numb in the hospital, telling people, ‘Oh, my sister just got run over by a car.’”

Her sister survived, but adult Cruz suspects she “would have been hysterical” if she had witnessed such a severe accident now. She has difficulty modulating the degree of empathy she feels and how much seeps into her personal root system. There’s a “back-and-forth dance between fiction and reality,” which she realizes “plays into a certain stereotype” of actors, but that doesn’t make it any less true. “I’m lucky to have it, but maybe it makes me feel or suffer things more. I can feel it; it’s like a hypersensitivity in every way—visually, to sound, to people’s feelings. It’s been one of the main things I deal with in therapy: how to work a balance so I can keep feeling those things without making those feelings my own.”

I share a great piece of advice I once heard, that one should approach new people as if they were grieving.

“Yes,” she says, nodding. “Always. And I would not change that. Sometimes [the characters I play] can be uncomfortable and painful. It’s hard to let them go, but at the end, I always feel they made me a little bit more compassionate than I was two months ago. And with the safety net that you know this is not your reality. It creates less judging and more compassion in every area of my life.”

Thanks to films such as Live Flesh and All About My Mother, Cruz has been a mother in the eyes of the world long before she became an actual mother. And now, she says, “at my age, 80 percent of the characters that I play will be about motherhood or divorce or abandonment or characters who didn’t want to have children or couldn’t or who lost children. I’ve played mothers since I was very young.”

“Because that’s how Almodóvar cast you.”

“Pedro always saw me as a mother.”

I tell her I don’t want to give him too much credit—genius can only extend so far—but I wonder if it’s fair to say his vision of her as a mother and her maternal sense got entwined along the way.

“I think so. We have known each other since I was 17. He would watch me going to talk to strangers just to see their babies. He always saw that strong, inevitable instinct in me, and I saw him see it. But also, ever since I was a little girl, I knew I wanted kids. But I knew I wanted them older. I wanted to wait until I felt I was ready. I was sure it would be the most important thing I would do in my life.”

Cruz is private about and protective of her children with Javier Bardem, Luna, 10, and Leo, 12 (her production company is called Moonlyon), even more than one would expect for someone in the public eye. She will not so much as confirm or deny if they are creative people like their mother, who studied classical ballet for nine years at Spain’s National Conservatory, or their father, a onetime aspiring painter and descendant of Spanish cinema royalty. “It’s for them to decide if they are going to have a job that is more exposed to the public or not. They can talk about that when they’re ready.”

It should come as no surprise that Cruz’s children do not have social media accounts, but they also “don’t even have phones. It’s so easy to be manipulated, especially if you have a brain that is still forming. And who pays the price? Not us, not our generation, who, maybe at 25, learned how a BlackBerry worked. It’s a cruel experiment on children, on teenagers.”

Who needs TikTok anyway when you have Javier Bardem in the house? “He sings and he’s a great dancer. And he does this amazing impression of Mick Jagger. He’ll imitate Al Pacino and De Niro talking to each other. It’s incredible.”

“Under what context does this come up—making dinner?”

“Truly, any situation.”

One can see how, for all the glamour (only a few days ago, she had friends over to give away gifted items, because she believes “you have to share the joy and keep it moving”), this is also a family of four with private jokes and tight schedules. Cruz will go straight from our chat to pick up her daughter.

Much is made in Hollywood, and with her in particular, about age. Or, rather, agelessness. Tedious as the topic may be, there are certain celebrities the media doesn’t seem to allow to age.

“But you know why I don’t worry about that?” she asks, smiling. “Because people have been asking me about age since I was twentysomething. I was more bothered then than now. Now it makes more sense, to discuss turning 50. It’s a huge, beautiful thing, and I really want to celebrate that with all my friends. It means I’m here and I’m healthy, and it’s a reason to have a party. But when I was 25, they would ask me these psychotic questions, things you would not believe, and the only weapon I would have was not to answer. Even now, on the red carpet, when they shout to ‘Turn around,’ I always pretend I didn’t hear what they said.”

This is true. If she does not like a question, the muscles in her face go slack and she stays silent. From 60 to 0, as it were.

“I did that?! When?”

I draw her attention to one hour ago, when I made a clumsy but obvious observation about the Ferrari casting: This is a movie about a sports car starring one actor named “Driver” and one named “Cruz.” Now imagine if she had stayed with Tom Cruise. We laugh now, but I tell her that, in the moment, her reaction was so piercing, I hesitate to bring it up again.

“I think you thought I was going to say something we couldn’t come back from.”

“I’m so transparent!” she says, throwing her head back. “See? It’s all on the surface! But I can’t worry about it.”

“Let me tell you a story,” she continues, gesturing at the muted horizon. “All of that is the area where I was born and grew up, where I went to school, where my mother had her hair salon. Somewhere in that neighborhood, I was walking with my dad after my two first movies had come out at the same time, Jamón Jamón and Belle Epoque, and a car passed by and a guy screamed, ‘I love you!’ and I swear to you, five minutes later, another car came by and another guy screamed, ‘Fuck you!’ And I looked at my dad and we didn’t say anything. But it was like, Okay. Here, in this moment, is a condensed preview of the nature of fame. And all that love and all that anger, I don’t think one is more dangerous than the other.”

Even now, on the precipice of 50 and after more than 60 films under her (now buckled) belt, she has difficulty discussing fame and wrestles with the construct of it. But I tell her that when I told friends I was going to Madrid to interview a celebrity, they had three guesses—and she is married to one and has done seven films with the other. “I say ‘known’ or ‘public,’ but I know, everyone knows, it’s ‘famous,’” she says.

She’s found an ability to insulate herself by doing fewer films and corresponding press than she used to (“I don’t have the ambition of my twenties and thirties, shooting nonstop; I did that for 20 years”). In addition to her excitement about a movie musical and a possible Nancy Meyers film (“I don’t know if it’s happening, but it’s very funny”), Cruz is currently directing and producing a “passion project” documentary she can’t talk much about yet, though a focus on children would be a natural guess. She’s spending her time in select pockets of Madrid, where she goes to a public gym several times a week. She gamely plays tour guide, jotting down a list of must-see places in Madrid and telling me to call her if I need anything.

“Here,” she says, sliding a bowl of Marcona almonds across the table, ever the mother. “Will you eat these?”

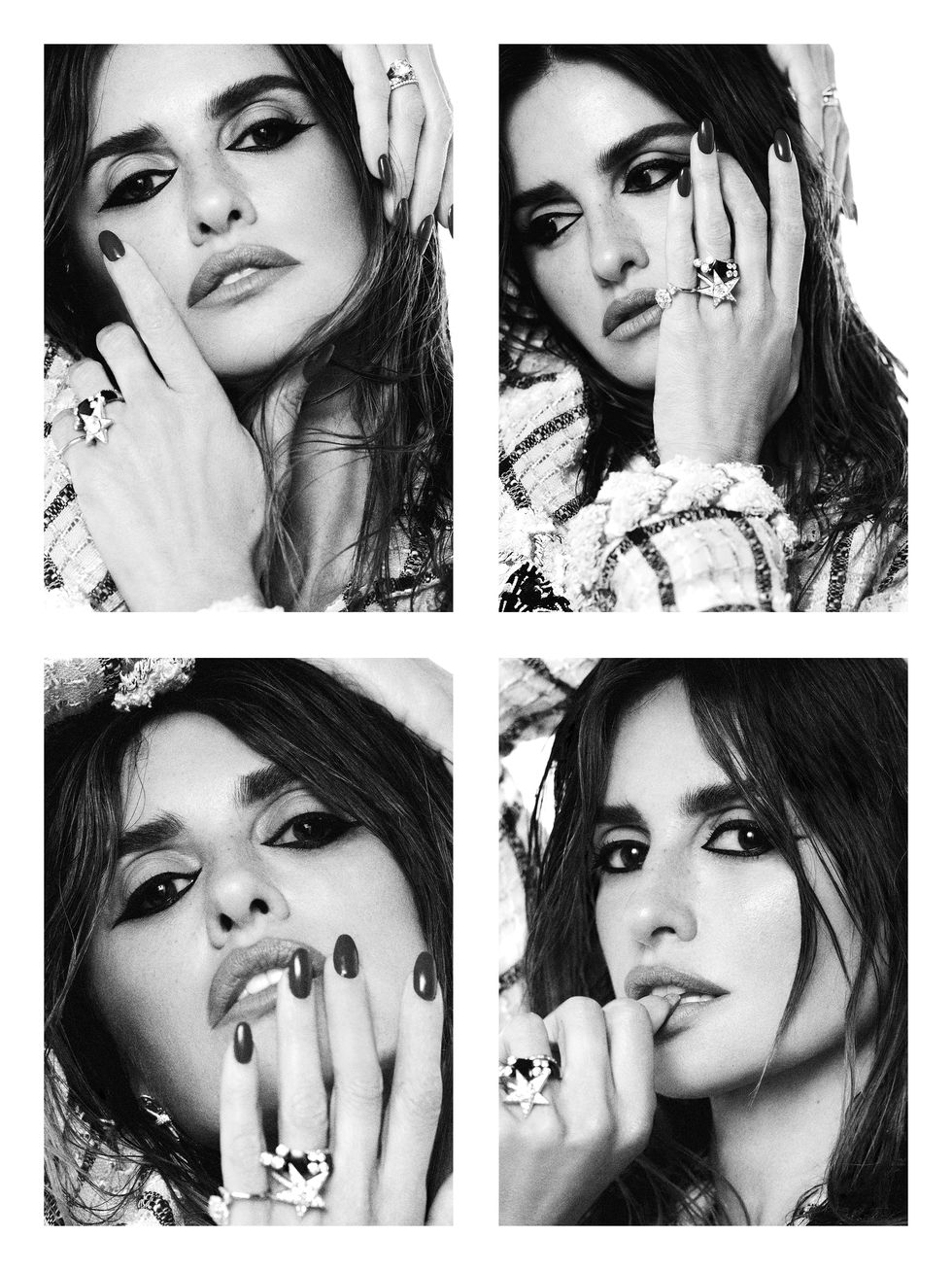

Hair by Pablo Iglesias at NS Management; makeup by Sofia Tilbury; manicure by Maki Sakamoto at The Wall Group; set design by Bette Adams at MHS Artists; produced by Day International.

This article appears in the February 2024 issue of ELLE.

Sloane Crosley is the author of three books of essays and two novels. Her memoir on friendship and loss, Grief Is for People, will be out on February 27.