‘We want to let people know before floods hit them’

Flooding can lead to the loss of life, homes and livelihoods, and the global risk appears to be getting worse.

Some 1.81 billion people – more than one fifth of the world population – now face “significant flood risk”, according to one report published by the World Bank.

It comes as numerous other studies warn that climate change is making floods more likely and severe. One from the United Nations last month said that the risk of coastal flooding will increase fivefold this century.

To help reduce the impact of flooding, a number of flood monitoring firms are now using artificial intelligence (AI) to help them sound the alarm before the waters rise.

Based in the Norwegian city of Bergen, 7Analytics is a team of computer scientists and geologists who offer businesses and local authorities real-time flooding predictions, and let them know which areas are particularly at risk of flood damage.

“We can actually predict, based on the weather forecasts up to seven days in advance, what flooding will happen, and it’s down to the very finest grain,” says 7Analytics co-founder Jonas Torland.

“All of this data takes into account where the water will flow, and where it will create problems. We can tell you that in five days you will have 50cm of water at your entrance, and we can tell you when it will subside.”

To do this, the firm’s AI software automatically studies not just the weather, but the geography of the land and rivers, how built up an area is, and its drainage capacity. Previously such flood prediction calculations would be done by standard software, but AI’s greater computing power and ability to learn means the work can be done more quickly and with much less human intervention.

The company was launched in 2020, and Mr Torland says that initially it was hard for it to raise funds from investors. However, he says that all that has now changed in only three years, as people are increasingly aware that flooding is a growing problem.

“It’s totally different now,” says Mr Torland. “Now we get investors coming to us, because they finally understood the value of adaptation [against flooding].”

Another company working in this field is London-based Neara. It uses AI to create digital flood simulations for the electricity infrastructure industry. These predicts how floods will likely unfold, so power networks can prepare and take action to minimise damage.

It claims that its data can show where it’s safe to restore power post-flood, which cables to switch off, where to divert power, and the exact locations that engineers should be sent to.

“With unpredictable flooding, I think loss of electricity is one of the most significant sources of devastation,” says Mary Cleary, chief marketing officer at Neara.

Ms Cleary adds that the digital models it creates for the utility networks “reflect in hyper realistic detail all the nuances there are, from the actual width of individual cables, to what the nearby buildings and vegetation look like”.

While both 7Analytics and Neara charge for their service, internet giant Google is now providing free river flood warnings in more than 80 countries via its Flood Hub platform.

This first launched in India in 2018, before expanding in 2022, and again this year, which saw it become available in both the UK and US.

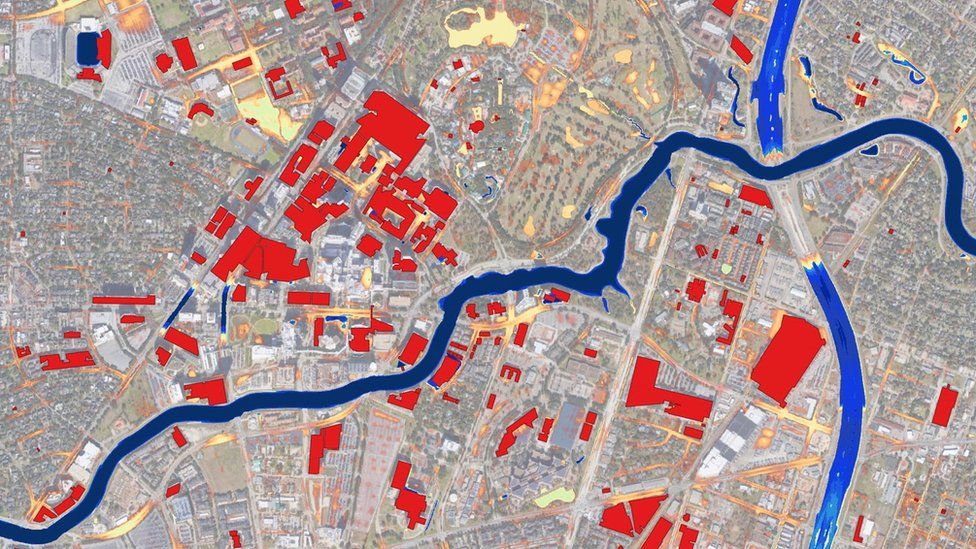

Flood Hub uses thousands of satellite images to create digital pictures of rivers and their surrounding lands. AI software then simulates how and when the rivers could flood after heavy rainfall.

It is said to be able to give warnings between two and seven days in advance, allowing authorities and members of the public to organise evacuations and other preventative measures.

In India, Flood Hub now sends 45 million people flood alerts via text message. Meanwhile, in Chile, TV stations share the warnings.

“Floods are one of the most devastating natural disasters, and impact hundreds of millions people per year,” says Yossi Matias, vice president of engineering and research and crisis response lead at Google. “We really want to let people know before floods actually hit them.”

He adds that they have learnt the AI tech can provide predictions in places where there is scarcity of historical data. “The nature of these global models is they can actually learn from experiences happening in other rivers where you have more data and more historical experience.

“That has enabled us to have predictions in 23 countries in Africa, where we have less historical data.”

However, weather and computer experts warn that there needs to be an element of caution when it comes to the underlying data that’s been collected for the AI to work on.

“The models are only as good as the data that they collect,” says Dr Amy McGovern, a computer scientist at the University of Oklahoma School of Meteorology.

“For example, imagine the places that very rarely flood. If you don’t have a whole lot of data there, then it’s going to be harder for it to predict the flooding there.”

Dr McGovern, who specifically researches the trustworthiness of AI in weather prediction, adds: “If you don’t have the data to train the AI model, it’s not going to do a great job. But a lot of us are working on that bias question.

“The key part of being trustworthy is making sure that you are responsible and ethical in your AI development, and that you’re paying attention to the biases in your data.”

However, she does say that AI is generally helping to make it easier to predict flooding, as it is “really computationally intensive” work that AI, with its greater computing power, can do far more quickly than standard computing.

Back at Google, Mr Matias is optimistic about the future extent of the impact AI can have on flood prediction. “Ideally, I’d love to get to a point where nobody is surprised by a flood coming their way, or for that matter, any other natural disaster, so that people can be prepared, and we’re not going to see loss of lives in places, or damages in places, that we don’t have to,” he says.