“He was so unloved”: Jason Isaacs on the man behind Cary Grant, a beloved persona created to protect

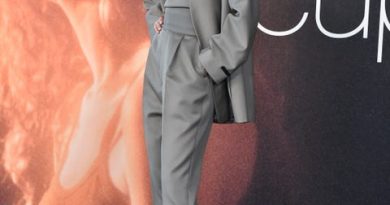

Throughout Jason Isaacs’ extensive career, the British actor has inhabited morally gray but iconic characters like the cunning death eater Lucius Malfoy in the book to film adaption of the “Harry Potter” series, the pirate Captain Hook in “Peter Pan” and even Captain Gabriel Lorca in “Star Trek: Discovery.” This time, he has chosen to portray one of the most famous men in Hollywood — actually the real, struggling man behind the dazzling persona Cary Grant in the Britbox show “Archie.”

The show is a multi-generational tale of the troubled actor known as Cary Grant to the world but originally named Archibald “Archie” Leach. “Archie” grants us a peek into the humble and abusive origins of Grant. It illustrates who Grant really was — or what parts of his identity he was trying to mask as he stuffed Archie so far down into himself so he could play Grant.

During our “Salon Talks” interview, Isaacs told me that Grant gamed the Hollywood system to get ahead. “Apart from the fact that he had the tools he really was incredibly charming and funny. He learnt to make people like him,” he said. “He learnt to make anybody like him. He was different in every situation. Anywhere he went, he could be exactly what you needed him to be.”

You can watch my full interview with Isaacs here, or read the transcript of our conversation below.

The following transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

“Archie” is about the tumultuous life of Cary Grant, but it’s not really about Cary Grant, it’s about Archibald.

Yeah, it’s not about Cary Grant at all. In fact, if it was a series about Cary Grant, I wouldn’t have taken the job because you’d have to be a moron to try and step into his shoes. He was the most beloved, fancied person in the world, and the most famous person in the world for about 30 years.

But in real life, he was the complete polar opposite. Of all the debonair, sophisticated man-about-town he was onscreen, he was really badly damaged and badly scarred from his childhood. Those wounds never healed, and he was really troubled. He made his way through many relationships and marriages, and that’s why it’s worth telling the story I think, in today’s world, even for people like you who weren’t born — neither was I really — when Cary Grant was famous, because, I don’t know if you’re watching this on your phone, your iPad, but how many people come through our devices whose lives look perfect to us. It’s a reminder that they really never are, and the more famous they get, the more likely it is that they’re f**ked up.

Can you tell me what those stark differences between Archie and this character that he’s playing in Cary Grant?

“If it was a series about Cary Grant, I wouldn’t have taken the job because you’d have to be a moron to try and step into his shoes.”

Literally the opposite. All the adjectives that will ever apply to Cary Grant are the opposite. In many ways, I think his screen persona that he worked on over decades that he curated so perfectly was a device. It was like an avatar. It was there to protect him. He thought, “If I can become that person” – and he did manage to fake being that person and be that person sometimes quite a lot – “if I can become that person, the world wouldn’t reject me.” Because he was so unloved. I don’t know how deeply you want to go into his childhood, but he was completely abandoned and abused and must have felt unloved.

His father left him, he was a violent alcoholic. His mother was taken away and then died. So he felt like he just wasn’t worth anything. But this thing he created on screen, not only could he make people love him in the flesh, he was very sexual, he learned to use sex as a tool, but he ended up making the whole world love him. Which I guess he would’ve thought, not consciously, but playing pop psychologist, he would’ve thought would fill the hole inside of him, make him feel like maybe he was lovable. But of course, it did the opposite, that’s what fame does to people.

What do you think made Cary Grant that guy, that most famous man in Hollywood?

First of all, the need. I mean, there’s plenty of people with a need. But I think he was beautiful for a start, which is incredibly irritating. I spent a lot of time talking to Dyan Cannon, who’s featured in the show. That particular marriage that produced a child is the one that we concentrate on. And she would say to me lots of really useful things about how damaged he was and how controlling he was, how angry he was and how much it hurt him to be so hurtful.

But then she would, every now and again, drop in things, which were a nightmare for an actor, like, “You have to understand, honey, Cary would walk into a room and everybody just their jaws fell up and he was so beautiful and sexy.” And I’d go, “Dyan, that’s really not helping me. Let’s get back to the psychological stuff.”

Apart from the fact that he had the tools he really was incredibly charming and funny. He learnt to make people like him. He learnt to make anybody like him. He was different in every situation. Anywhere he went, he could be exactly what you needed him to be. He carried a lot of shame for that later in his life for some of the things he had to do early on to get where he wanted to be.

In his most famous roles, what role do you think Archie played a role in performing?

None.

None?

You’ll never see the real man in the screen. What happened was he started off, he was a kid, and so abandoned, neglected, it happens to a lot of us, he found the theater. He found a place where it felt warm, it felt like a family. It felt like somewhere you could belong. It was the First World War, and so we joined this acrobatic troupe, which would normally have been adults, but the guy had kids instead. His dad didn’t care, and so he signed up and he traveled round with them, expelled from school, and they went to America and he stayed, because he had nothing to go back to England for. He was desperate, he was hungry. I mean, literally physically starving a lot of the time, and he learned to be a carnival barker, a stilt walker. He sold ties on the street. Did a lot of things, some of which he carried a lot of shame for later in his life. He was for hire by people that needed entertainment. I won’t to go further into it, but which ladies would hire him and who knows who else.

Then he became a vaudeville act. He did knock down comedy and acrobatics. He did musicals, although he couldn’t sing. He was so gorgeous, people put on the musicals and he kept on being hired even when the musicals closed because he was just so handsome. He couldn’t really do the musical stuff, but he continued to do comedy. When he first got into Hollywood, he did a screen test, he got rejected for being rubbish. But then he went back a couple of years later. When he got into Hollywood, he did breakneck comedy sketch stuff.

One of the films in his early days, it was a very different actor that I love so much, is called “His Girl Friday,” and it’s this really end of pier knockabout comedy where they deliver the lines at five times the pace. It’s like the medical disclaimers at the end of a hemorrhoid cream commercial, just it’s so fast. His double takes and triple takes and his pratfalls are so fabulous.

“He was a man of tremendous extremes. Today, I think you’d label him with acronyms, OCD and ADHD and a million other things.”

But what was interesting, you asked me when Archie appeared, did you ever see Archie on screen? Much later, he’s been the biggest star in Hollywood for a long time. He’s had a number of marriages, lots of relationships. Alfred Hitchcock got to know him socially and Alfred Hitchcock knew the real man and knew that he was nothing like the suave ladies’ man that he was on the screen or the clown. He cast him in some very dark roles, some very dark and manipulative roles, and really gave him a second career. That’s when it was a boost, he was almost giving up. He made a lot of money and he didn’t quite know what to do next, and Alfred Hitchcock rebooted his career as a much more complicated actor and continued to cast him in dark parts.

There’s a film called “Notorious” where he persuades someone that he is falling in love with, who’s the daughter of a Nazi collaborator, to go and sell herself, to hook up with someone he suspects of being a Nazi sympathizer. She marries him, she sleeps with him, because she’s doing the job she’s forced into doing, and then he judges her and treats her harshly for it, and it’s brutal. I think Hitchcock knew who the real complicated Cary Grant was, and he learned to use that image on screen.

That version of him, he is funny, he is charismatic, he’s obsessed with women. How is it playing that man when he’s at maybe the peak of his success?

Well, I’m not playing him. You’re talking about the character on screen that you know.

Yes, the character Cary Grant.

I did a ton of work because I was scared, frankly. I read all the biographies. I read everything that exists, and I read Jennifer Grant’s book, his daughter, although she saw this loving dad, which is not that useful. But I read Dyan Cannon’s book, which chronicles really beautifully and painfully what it was like being in love with the world’s most desired icon when they shut the front door and he turned into a nightmare, turned into the opposite. This manipulative, controlling, angry, heartbroken man who, for instance, took acid hundreds of times with a therapist to try and rid himself of his nightmares. That’s who I played, I played the guy when he gets off the set and shuts the door. There’s little bits of him being charming, when he was wooing her he was charming and we do a couple of bits of the films and he can be funny, but really it’s about the anger and the pain and the stuff that he has subdues all the time that I get to play.

There’s a physicality to that. You’re wearing a lot of tan from what I see in the show and the prosthetics. Can you speak to that as well?

He was a man of tremendous extremes. Today, I think you’d label him with acronyms, OCD and ADHD and a million other things. He drank till his liver almost exploded, a lot of things. But he was extreme in so many areas, and one of them was tanning. Someone had told him early on that he needed to be brown.

He’s so orange.

Well, yeah, he was orange, but he walked around with one of those silver reflectors all the time, right until he was old. He was dark brown, he was mahogany, and the directors of photography had tremendous trouble lighting him. They would always try and over light him and shade other people. He was in a film called “Gunga Din,” which is about wars in India and the Indian actors were lighter than him. It was troubling. But that’s just an indication of how extreme it was.

Anyway, what did we do? I was never going to look like Cary Grant. I was never going to be as Dyan Cannon said, the sexiest man in any room I walk into, that’s just not possible. But he famously had a big cleft chin. We indicated that because I don’t have one. He had big brown eyes, beautiful big brown cowy eyes. So some poor lady’s job was just to put contact lenses in the morning and take them out at night and put up with me whining about it. Then he had different hair at different stages. He got a bit thicker when he gave up acting, so we had some prosthetics to make me a bit heavier. But the thing that really does it I think, in many ways is that he was the best dressed man in the world for 30 years, designers worshiped him. It was the other thing, Dyan Cannon would say to me, “He had a body, honey. Oh my God. You put clothes on him, it was like Naomi Campbell, I’m telling you.” And I go, “Again, Dyan, let’s get back to something useful.”

I had the greatest tailors in the world make all my suits. They had nothing left in the costume budget at all, they had to scavenge around thrift bins, so I’ve got six or seven, I didn’t keep, I didn’t get, they went back into the stock. But I had the greatest tailors in the world make all these suits. You just walk differently. And then there was video of him walking differently at different stages. So I walk differently when I’m 80 from when I was 50 and so on. The hardest thing was the voice.

I was going to ask you about that. He has this mid-Atlantic voice. He’s British-American. You’re British, you’ve played Americans. What’s that experience like?

I play Americans all the time, but that’s an American voice. I can do accents, but that was an accent. He had a very unique sounding voice, really peculiar. When I did eventually take the job because I didn’t want to take the job at first, I resisted them, because I thought it was a poisoned chalice. But then once I read the scripts, I couldn’t stop myself.

“I was never going to be as Dyan Cannon said, the sexiest man in any room I walk into, that’s just not possible.”

The thing that loomed all the time was wondering about the voice because everybody asked me, everyone went, “Can you do the voice yet?” And I went, “No, I can’t.” I didn’t do the voice for anyone, for the director or anyone up until the first time the cameras rolled because I couldn’t find reference anywhere. There’s only the films, but I knew he didn’t talk like that. That’s what Jennifer said to me, her dad was much more English in real life. He was always correcting her, making her do English pronunciations.

I just couldn’t find [anything]. He didn’t do any talk shows. He didn’t do any radio interviews. He didn’t do anything anyway. Of course, I realized why, because he didn’t want the public to see who he was. He never wanted to give away what his real nervous energy was. He was riddled with anxiety and stuff. So I was despairing a lot. Then I found something, I read this interview, it looked like a transcript. I saw the byline, the guy wasn’t a journalist, I couldn’t find him anywhere.

Anyway, I tracked him down on social media and I sent him direct messages and eventually he got back to me, and it turns out he’d done an interview in the last year of Cary Grant’s life when he was just a student. He wrote to him saying, “Can you answer some questions?” And he got a message back going, “Call and we’ll have a chat.” He went down to the university radio department and he phoned the number thinking, “I don’t understand what’s happening here.” Cary Grant got on the phone. He couldn’t believe it. He was 22. He started asking him questions, and they stayed on the phone for an hour. He was at the university radio department.

The first thing Cary Grant says is, “You’re not recording this, are you?” And he goes, “Well, I was thinking . . .” And he goes, “Don’t. I don’t want you to record it.” And he goes, “Yeah, well, sure.” He signaled to his friend, so they did the interview and at the end of the interview, his friend went, “I mean, I did record it obviously.”

I tracked him down and he got very shirty with me, very like, “Who are you? Why are you asking? How did you find me?” I said, “I just want to hear that tape. I want to hear him talking normally, not how he talks in the movies.” He said, “I’ve never played it to anyone. It’s not right. I promised him I wouldn’t.” I went, “I’m playing it with the blessing of his wife and his daughter and I just want to hear what he talks like.” So he sent me a private link. The voice I do in the show is as close as I can get it to that voice.

You play these morally gray characters, these dark characters. Your character in “Harry Potter,” “The Patriot,” and now in “Archie”? Do you like playing that moral gray area?

I just like playing human beings. I like playing three-dimensional human beings. You’re a writer, so it’s all about the writing. You can’t play three dimensions if there’s only two on the page, you just can’t do it, but when there’s three on the page, and you can do that in long-form TV like “Archie,” then you get to see a rounded human being.

If you’re lucky, you start people discussing things at home. You want to engage them and entertain them, but if you’re lucky enough to be able to put full human beings on the screen, they’re complicated and they also contradict themselves and there’s stuff to discuss afterwards. “Why would he do that?” “She should have done this, but then he wouldn’t have said that.”

We all get that in our own lives. We’re all different. If we follow any person around all day, we’re different people in different situations and on different days we behave differently. You don’t get to do that in a movie often. You’ve got one journey and there’s normally only one character that can have a full emotional journey, but in TV you can do more.

This is as much a story of Dyan Cannon, and how this young woman was wooed by this much older man, till eventually she fell for him, and then realized she’d got in so deep. The whole world worshiped him and who was she going to tell that he was behaving like this? So I’m just drawn to good writing, because good writing makes me look better as an actor.

Absolutely. That trauma and that difficulty of Archie’s backstory, how does it inform your performance?

I don’t know how much you are thinking now about growing up as a kid. You’re probably not thinking much about it, but it’s informed everything about who you are now, even though you’re sitting here asking the questions. You just do all the work, I try to imagine . . . It’s a funny old job, acting, because it’s all about imagination. People who don’t do it think it’s about learning lines, but you have to try and program in as much as possible this background where he’s rejected and abandoned and beaten and abused in many ways and desperate for approval and get all the facts in and then forget about them. Because I’m here having a conversation with you, I’m not thinking about what happened this morning. I’m just thinking about this engagement. But you hope that that work has somehow bubbled into your foundations and plays through. Most of it, I won’t take the credit, is Jeff Pope, the writer. He’s done all that work elsewhere in a lonely room, and it’s in the dynamic that he’s written.

He’s angry a lot and then he’s angry at himself often a lot for having been angry, and he’s controlling things, so the actions that he takes, I think those are the manifestation of these childhood scars. I’m not a psychiatrist, but my understanding is he wanted to control anyone he was with and everything around him as much as possible, because his early life had been such chaos, such damage there, and such terror and fear of, “Where’s the next meal coming from? And what are these people going to do to me?” If he could just make everything how he wanted it, then maybe chaos wouldn’t come in through the door. So you play that. A lot of the time, people who are angry are scared, a lot of people who are controlling are frightened of being of control and you play the opposites.

Speaking of these damaged characters, for all the Potterheads out there, what would you say if HBO Max gave you the call and was like, “Hey, we want you on the new “Harry Potter” series?”

Well, they wouldn’t because they’re rebooting. They wouldn’t phone Daniel and ask him to play an eleven-year-old either.

But hypothetically?

I’m too old to play that part.

Really? Would you think so?

Yeah, course I am.

Even though the fans love you and you feel like there’s a connection to that character?

Also, there was a magical thing that happened. None of us were doing a job, everyone was a fan. While we were making it the books were coming out and the world was abuzz with it. The world is still abuzz with the books. We all knew and felt that something special was happening on the set and they’re going to have their own experience of it.

“Jo’s very unusual and adamant stand on it coming from her point of view—I’m a straight white man of 60, and I don’t think it’s my place to opine on those things.”

For me, being Lucius is completely tied up with being Tom [Felton]’s dad and our relationship and Helen, brilliant Helen McCrory who played Narcissa. It also, it’s so different now because Lucius is a complicated character because the purity of race, that Nazi eugenics that he was spouting, the whole things about Muggles and wizards is what you heard Trump say. You don’t need to look very far to find characters that are as monstrous and as convinced that the world was better when people like them ruled the world. Today will be a very different story. It has different resonance because there are those right-wing demagogues in power around the world. Thank God, not at the moment in America. But so it needs new energy. I gave the best to Lucius Malfoy I could give at that time.

Talking about the “Harry Potter” creator, JK Rowling, you have said in the past that you two have differing opinions about things and that you would want to have a conversation about it with her. Have you had that conversation? What would you like to share about that, if you can?

Well, this is a discussion about trans issues and trans rights. Jo’s very unusual and adamant stand on it coming from her point of view — I’m a straight white man of 60, and I don’t think it’s my place to opine on those things. I’ve said some things online and supported various people, but I don’t ever want to get into a public argument with Jo. She has things she believes fervently in and she’s explained herself, and it’s not a discussion that I should be part of, I think. I worked for her charity Lumos before these issues came to the forefront, and I’d seen her put enormous amounts of money and energy into making children all over the world’s lives better. For that part of her that I saw then, I had tremendous admiration. Her views on women’s issues and trans issues are hers, and they’re not for me to discuss in public.

What do you say to the fans who have complicated feelings about the films now?

I don’t tell other people what their feelings should be about anything. I do know this only, that it’s a complex issue and a really sensitive issue. A lot of people get very upset or angry and feel very scared about it. Those things need to be discussed and the place not to discuss them is on this or in social media because views only get more polarized and there’s no compassion there. Those aren’t the places for these discussions.

Altogether, what would you say of your “Harry Potter” experience and to the people who still love these films and books?

Oh, those stories have nothing to do with any of the individuals concerned. You can love those books and stories. I’m so privileged. I get to travel the world and meet “Harry Potter” fans who come up who approach me and get to tell me how those stories saved them times when they felt excluded, when they felt alone, they felt bullied, when they felt there wasn’t a place from the world. Those stories and those characters gave them a safe berth, made them feel like there would be a place and there’s a community for them, and that’s such a powerful thing. It’s divorced from whoever wrote it, whoever directed it, whoever was in it. Those stories exist in the world and they do such good, and I’m just lucky to be associated with them.

Watch more

“Salon Talks” with actors