The slow and delicate aircraft taking on spy missions

Most military spying is conducted from satellites hundreds of miles above the Earth’s surface.

But there’s a new entrant in the old game of keeping an eye on your strategic opponents, and this new spy is surprisingly sluggish.

Phasa-35 moves so slowly it can appear to be going backwards.

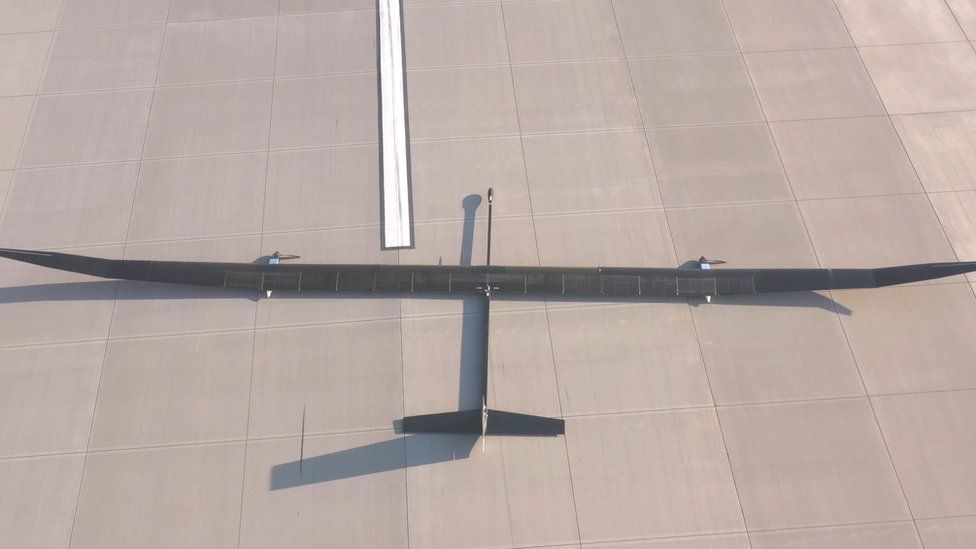

This weird, elongated British aircraft is powered by small electric engines attached to elongated wings encasing solar panels. These capture power during the day and keep the two engines turning at night.

Solar power is stored in packs of lithium batteries like phone batteries. Having so many batteries means some can fail during weeks of flight without any impact on endurance.

With a 35 metre wingspan, pencil-thin carbon fibre fuselage and 150kg all-up weight Phasa-35 looks a little flimsy.

The wheels it rolls on to take off are abandoned on the ground, the machine landing slowly on its two engine pods, and changing the bruised propellers after every flight. It resembles an arrow that has grown long thin wings.

That fragile appearance, more insect than aeroplane, is one clue as to why BAE Systems chose a US military range in New Mexico to test Phasa-35 in July this year.

The normally-benign climate in the South-West US gave the aircraft its best chance of climbing to 66,000ft, twice the altitude of a commercial jet, without encountering strong winds that might tip the delicate machine over and into a dive earthwards.

Clambering to its stratospheric destination at a lazy 55 mph the machine can travel backwards in relation to the earth if it hits winds of higher velocity as it noses upwards through weather systems.

One of its rivals, the Zephyr solar-powered high altitude aircraft, flew for up to 18 days during 2021 tests in Arizona.

Zephyr was also built in the UK, for Airbus. But a more ambitious flight lasting 64 days ended in a crash in July 2022 due to high-altitude air turbulence.

In the rarefied air above 60,000ft such aircraft can dodge the weather, but they also get very little lift from their wings, leaving them vulnerable to any buffeting or gusts.

This set-back took place while the Zephyr was testing the potential for such aircraft on behalf of the US Army.

Military minds on both sides of the Atlantic are pondering how to use them as satellite substitutes. They belong to a new category of unmanned aircraft, the High Altitude Pseudo-Satellite (HAPS).

In the UK the Ministry of Defence (MoD) says early pseudo-satellite trials have evolved into Project Aether. This embraces high-altitude balloons as well as solar-powered planes.

Carrying a small payload of cameras or other sensors one HAPS could sit above an area of interest for months, eavesdropping on communications or relaying information on hostile troop movements.

The suspected Chinese spy balloon shot down off the US coast in February appeared to heft a large package of electronic equipment. By contrast a pseudo-satellite is limited in the weight it can carry.

One key attraction of such spying equipment is price – they cost a fraction of launching a satellite into space.

But before this vision is realised potential customers must be convinced the aircraft can stay aloft long enough to complete its job.

Weather forecasting on a very detailed scale plays a big part in this project. As the MoD states, “the understanding of how to operate pseudo-satellites within the stratosphere (above 60,000 ft) is novel but maturing all the time.”

The Phasa-35 trials relied on a laser sensing system that measured weather conditions and wind speeds every 500ft up until the pseudo-satellite’s final altitude. This granular approach to weather forecasting allowed Phasa-35 to dodge any unwelcome turbulence.

Phil Varty, head of business development for Phasa-35 at BAE Systems, points out that loitering pseudo-satellites can stay “fairly still”.

This is attractive for military clients who want to observe one spot for weeks, and for commercial clients who might want to put hundreds of pseudo-satellites up in formation to offer internet connections across a remote area.

Mr Varty’s team are building up experience to take on tougher weather conditions, though just like a space launch they will never gamble with thunderstorms.

He notes that pseudo-satellites have much in common with space exploration. “This is all a bit like the space industry used to be, it’s just opening up.”

In theory Phasa-35 is in the running to win records for high-altitude endurance, but Mr Varty wants his engineers to keep their feet on the ground. “I keep telling the team we’re not chasing records here.”

Military planners fear that jamming or destruction in space might deprive a nation of its spy satellites just when they are most needed. So pseudo-satellites represent a relatively cheap back-up.

Douglas Barrie, a defence and aerospace specialist at the International Institute for Strategic Studies think tank in London describes this as “an alternative approach to what a spy balloon gives you. A pseudo-satellite can sit over an area of interest for days and it’s covert, there’s not much radar signature. This is a technology on the cusp of having its time arrive.”

BAE Systems plans to expand the capability of Phasa-35 towards 2025. Four more aircraft will be made at Alton in Hampshire, though the wingspan means each one gets broken down into parts to be assembled at its launch site.

Italian aerospace giant Leonardo has built a pseudo-satellite called Skydweller and is talking to Saudi Arabian telecoms company Salam about it. Salam is interested in using pseudo-satellites to bounce 5G Internet signals down to earth.

But Leonardo won’t talk about Skydweller, possibly because going slow turns out to be very hard work indeed.