Even Republicans like Richard Nixon were once champions of the environment. What happened?

Five days before astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot upon the Moon, the American president who sent him there dispatched his Vice President to go on an important mission of his own. Speaking to the American Medical Association Convention, Spiro Agnew reflected that although America was “capable of catapulting men to the Moon,” the nation was also “in mortal danger of devouring its irreplaceable life-sustaining elements through simultaneous genius and foolishness.”

Even as NASA under the Nixon administration had used the “blessings” of modern technology to forever change history, “the curse of modern society is man’s inability to eliminate — or at least to neutralize — the adverse effects of his own creativity,” Agnew said.

“Carter’s policies, had they continued, would have been bad. But Reagan’s were downright cataclysmic.”

Agnew was referring to environmental pollution, of course. His tone reflected the bipartisan consensus which existed at the time on the need for environmental reform: “We are bringing a national plague upon ourselves. It is the plague of a polluted environment.”

As humanity endures extreme heatwaves, wildfires, massive floods, ecosystem collapse and the other consequences of climate change — which is occurring because of carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels — it is imperative to look back at recent American history and examine how things might have gone differently. At first glance, it is telling that a Republican president like Richard Nixon passed pro-environmental policies at all, given that the modern GOP is staunchly against environmental reforms.

Although Nixon was more liberal on domestic issues than many of his contemporaries were willing to admit, his support of eco-friendly causes had less to do with conviction than with pragmatism. Nixon read the room, so to speak — and, at that point in American history, reading the room meant supporting environmental reform.

Nixon read the room, which meant supporting environmental reform.

“Nixon was and is overrated as an environmental president,” David Helvarg, Executive Director of the conservation activist organization Blue Frontier Campaign, told Salon by email. “Democrats in Congress pushed through a range of effective legislation like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act and seeing their popularity Nixon signed them into law rather than veto them.”

Rick Perlstein, an American historian and journalist who has penned acclaimed books on the 1960s and 1970s like “Before the Storm” and “Nixonland,” pointed out to Salon that Nixon worried about running against Democratic Sen. Edmund Muskie of Maine in the 1972 presidential election. Polls consistently showed that Muskie would be a tough candidate for Nixon to beat, and because Muskie was the main environmental senator with “a storied career” promoting anti-pollution legislation, being pro-environment could help Nixon co-opt one of Muskie’s signature issues.

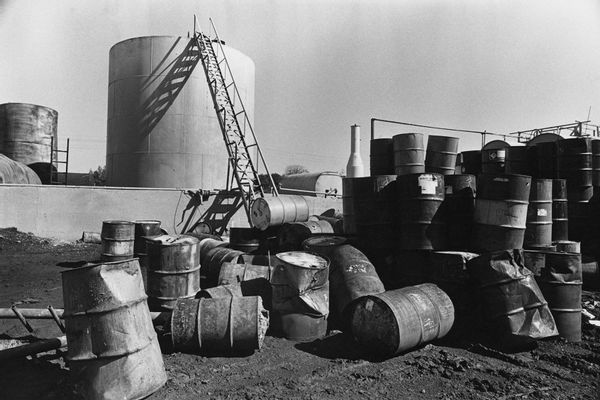

Dumped barrels containing hazardous chemicals remain on a 4.5 acre site after the Silresim Chemical Corp. declares bankruptcy, Lowell, Massachusetts, USA, 22nd August 1978. (Barbara Alper/Getty Images)If Muskie was going to garner headlines by quipping to automobile companies that they shouldn’t stay in business if they couldn’t adopt rigid pollution controls, Nixon would do so more substantively by creating the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Dumped barrels containing hazardous chemicals remain on a 4.5 acre site after the Silresim Chemical Corp. declares bankruptcy, Lowell, Massachusetts, USA, 22nd August 1978. (Barbara Alper/Getty Images)If Muskie was going to garner headlines by quipping to automobile companies that they shouldn’t stay in business if they couldn’t adopt rigid pollution controls, Nixon would do so more substantively by creating the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The EPA was far from Nixon’s only landmark environmental policy. He amended the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act to strengthen regulators’ ability to clean up the environment; created the White House Council on Environmental Quality and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; and repeatedly directed federal energies toward controlling air pollution, water pollution and the safe disposal of hazardous waste materials. These were proactive measures that made a real difference in improving the quality of the environment — and these policies channeled an ethos that could have nipped climate change in the bud, assuming it had lasted beyond the 1970s.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“Yet the science was well-enough known to anticipate that more warming would likely occur given a continuation of fossil fuel burning. And that, of course, is what has happened.”

“Warming had been muted by sulphate aerosol pollution (the same pollution that caused acid rain was also offsetting some of the CO2-driven warming by reflecting sunlight back to space),” Michael E. Mann, a professor of Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania, told Salon by email. “Yet the science was well-enough known to anticipate that more warming would likely occur given a continuation of fossil fuel burning. And that, of course, is what has happened.”

Indeed, the Democratic president who followed Nixon and his successor Gerald Ford (a Republican who briefly assumed office after Nixon resigned in disgrace due to the Watergate scandal) was Jimmy Carter, who famously installed solar panels on the White House. Carter intended to signal technology as a solution to a nation in danger of (as Agnew had put it) “devouring its irreplaceable life-sustaining elements through simultaneous genius and foolishness.”

“Jimmy Carter established himself as having environmental concerns and Frank Press from [the Massachusetts Institute of Technology] wrote a memo about [the] possibilities of catastrophic climate change to Carter in July 1977,” Kevin E. Trenberth, distinguished scholar at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, wrote to Salon. He added that “Carter’s concerns have proven real and, unfortunately, before their time.”

Trenberth praised Carter for some of his policies including setting up tax credits for home owners for installing solar panels in 1977.

“I took advantage and had solar panels installed on our house in Boulder,” Trenberth said. “These heated a fluid that took heat into my house and heated water in a huge 200 gallon tank. So our hot water was essentially free from then on.”

Like Mann, Trenberth noted that if the same ethic which led to pro-environmental legislation in the ’70s had lasted, we may quite literally inhabit a different world than the current climate change-ravaged one.

“With the 1976-77 El Niño event, climate change in terms of global temperatures was kicked off. But at the time, this was not that unusual,” Trenberth explained. “Only in retrospect can we now see that it was about 1976 that the climate change signal emerged above the noise of natural variability.”

“With the 1976-77 El Niño event climate change in terms of global temperatures was kicked off. But at the time this was not that unusual.”

Perlstein, for his part, was more critical of Carter. He argued that the president “gets all this credit for this highly symbolic action of putting solar panels on the roof of the White House. But if you actually look at his energy plan … its priority was much more than conservation, but was what I would call ‘economic nationalism.’ Fossil fuels came from these unstable countries in the Middle East, but we have lots of coal here. So he incentivized factories to switch from petroleum fuel power plants to coal.”

Yet despite these less-than-environmentalist actions, Perlstein emphatically stated that Carter’s approach — which at least acknowledged scientific reality, even if it sometimes subordinated that knowledge to political strategizing — was better than what followed.

“Carter’s policies, had they continued, would have been bad,” Perlstein wrote. “But Reagan’s were downright cataclysmic. He and his advisors simply despised the notion of using the power of government to regulate environmental harm.”

The problem, in terms of American history after the 1970s, is that Carter was followed by true believers of a concerted anti-science campaign, one led by the businesses most responsible for polluting: fossil fuel companies like ExxonMobil, BP and Shell. Carter’s successor, Republican Ronald Reagan, was something that Nixon had not been — overtly hostile to science.

“Corporate America just became more activist, politically, in all sorts of ways, in much more aggressive ways, partially because their profits were falling,” Perlstein explained. This story is discussed in his book “Reaganland: America’s Right Turn 1976-1980.” Thanks to the rise of Reagan and his right-wing movement, “another thing that changed was an ideological opposition to the very idea of environmentalism.”

Whenever possible, the Reagan administration sided with polluters over environmentalists, and during the 1980s climate change significantly worsened instead of improving. Subsequent presidents embraced Reagan’s conservative philosophy when it came to environmentalism, and by the time Reagan’s fellow Republican George W. Bush was in office, that conservatism seemed to always be accompanied by climate change denialism, as it is today.

According to Mann, “The fossil fuel industry and the Republican party that has become beholden to them” led the charge in destroying the bipartisan consensus that once existed to clean up pollution, and by extension climate change.

“It wasn’t always that way. George W Bush, as I recount in ‘The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars,’ actually campaigned on climate action and appointed a climate-forward EPA administrator (Christine Todd Whitman). It was only when [Vice President] Dick Cheney took over energy and environmental policy midway through Bush’s first term that the party became a wholly-own subsidiary of polluters, as it is today.”

Mann added — referring to a subsequent historical occasion in which a pro-environmental politician lost to an anti-science one — “If Al Gore’s apparent victory [in the 2000 election] hadn’t been taken away by a Republican-leaning Supreme Court, we would be in a much, much better place today.”

Read more

about climate change