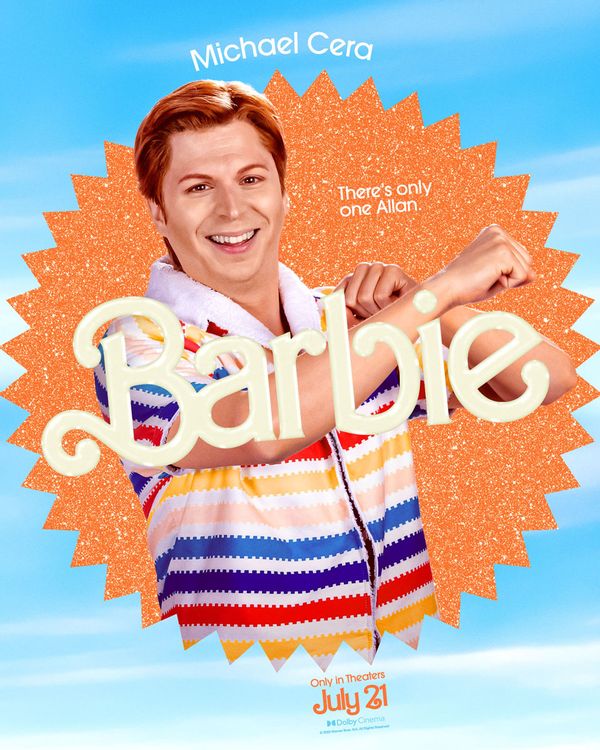

The secret “Barbie” message everyone can get behind is that Allan is amazing. He is also like us

All things considered, it’s a small miracle the right-wing fun police obsessed with ripping the legs off “Barbie,” and good times in general, hasn’t gone in harder on Allan. The discontinued doll has all the traits joy killers look for in a soft target: designated as “Ken’s buddy,” not his friend, Allan screams beta male, a type his human counterpart Michael Cera excels at playing. To the LGBTQIA audience he’s as queer-coded as “Earring Magic Ken” without the flashy clothes or BDSM pendant.

Allan’s rainbow striped top is its own fashion don’t, as if Mattel intentionally boxed him ugly casual wear to encourage kids to follow its main sales pitch suggestion: He can fit into Ken’s clothes. Wow!

Ask anyone who had to wear hand-me-downs to school back in the hyper-materialistic 1980s and 1990s, and they will concur that nothing screams, “Ostracize me!” like recognizably outdated and used clothing.

Marching through your formative years wearing highwaters and vision-damaging patterns is a surefire way to build character in a kid, and that goes some of the way to explain Allan.

In Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach‘s script, Helen Mirren‘s narrator contributes a little more detail when Margot Robbie‘s Barbie heads to Barbieland’s fake beach for a stroll. Upon arriving she’s greeted by an assortment of Kens, starting with her counterpart Stereotypical Ken (Ryan Gosling) before friendly hellos rain down from other Kens played by Simu Liu, Kingsley Ben-Adir, Ncuti Gatwa and Scott Evans.

A nation under the groove of “Barbie” has fallen hard for a doll almost completely forgotten by popular culture.

Robbie’s Barbie also exchanges perky hellos with fellow Barbies played by, among others, Issa Rae, Alexandra Shipp, Dua Lipa, Hari Nef, Ana Cruz Kayne, Emma Mackey, Nicola Coughlan and Sharon Rooney. Every interaction is artificially bright and friendly, except for the terse hellos exchanged by Liu’s and Gosling’s Kens, who are rivals.

Then Allan says hello to Barbie. His greeting is warm, real and not as loud as everyone else’s. When Barbie sees him, she acts just short of surprised, as if he isn’t there with everyone else every day. “Oh – hi, Allan!”

At this Mirren’s narrator deadpans, “There are no multiples of Allan. He’s just Allan.” Throughout the film the narrator pops up here and there without warning or explanation, calling attention to bonus ironies for our amusement. The Barbies and Kens don’t hear her, but Allan does. When she points out in a flat tone that Allan is “just Allan,” Ken’s buddy replies in a tone merging sheepishness with befuddlement, “Yeah I . . . I’m confused about that.”

This is the moment a nation under the groove of “Barbie” falls hard for a doll almost completely forgotten by popular culture. Millions are embracing Allan as the movie’s surprise hero, reflected in the price of those long-rejected Allan dolls spiking on eBay, to TMZ’s delight. Thank Cera’s signature vibe for part of that. He may not have been the only actor up for the job, but it’s nearly impossible to imagine, say, Jonathan Groff delivering the correct proportions of common sense and cheer that makes Allan shine as the one genuine fellow in a pleasantly pink and plastic world.

That could be because he can be anything the audience needs him to be. Allan isn’t a blank slate, but he is an open book; he doesn’t entirely fit in, but everyone agrees he belongs there.

Michael Cera as Allan in “Barbie” (Warner Bros.)In a sea of Ken and Barbies, Allan is content with his place in the world as long as everyone’s happy and nice to each other. He doesn’t necessarily want to be alone, but he’s fine with being left alone. That makes him the doll for the anti-Barbie crowd. Allan represents the rest of us.

Michael Cera as Allan in “Barbie” (Warner Bros.)In a sea of Ken and Barbies, Allan is content with his place in the world as long as everyone’s happy and nice to each other. He doesn’t necessarily want to be alone, but he’s fine with being left alone. That makes him the doll for the anti-Barbie crowd. Allan represents the rest of us.

In our reality, a guy like that might form ‘NSYNC – a group “Barbie” confirms is completely made up of Allans that went rogue without anyone ever noticing. “Yes, even him!” says Cera’s Allan, anticipating disbelieving rebuttals while ignoring that the Allan he’s referencing is no longer as adored or adorable as an Allan should be.

Of course in 1964, when Mattel introduced Allan, the doll had no behavioral traits aside from what the toy company assigned to him. As it turns out “buddy who can fit into Ken’s clothes” didn’t do much for Barbie-loving children. He and Barbie’s more sensible pal Midge, who was introduced in 1963, were designed to date each other and go on double dates with Ken and Barbie.

Another Alan – spelled with one L – appeared on toy store shelves in 1991 as a brunette with a European tennis player’s shag. This Alan was made to marry Midge, get her knocked up, and piss off parents groups who worried an eternally ready-to-pop Midge (played by Emerald Fennell) would encourage teen pregnancy.

Ken was always an accessory, not a necessity. So what does that make Allan?

Eventually it became clear that neither Barbie’s juvenile fans nor their parents viewed Allan, or Alan, as a necessity. If a child wanted a male-appearing, genital-free doll in Barbie’s life, they got Ken. More likely they went without or borrowed their sibling’s G.I. Joe.

This was always the conundrum of Ken – it’s never just Ken. It’s always Barbie and Ken, which drives Gosling’s toy man to despair and eventually to a childish interpretation of patriarchy.

There’s a scene where Robbie’s doll remarks to America Ferrera’s human, Gloria, that men are superfluous. There’s no malice in her voice when she says this since from her experience, – which reflects that of the girl or woman playing with her – that’s true. Barbie is the center of her universe of play.

What she really means, though, is Ken is superfluous. Ken was always an accessory, not a necessity. As the movie establishes, what Ken is to Barbie is never specified. As his power ballad bewails, he’s just Ken.

So what does that make Allan? This should induce a crisis of confidence in a doll coded as a boy, and a lone one at that, in a land ruled by Barbies where the Kens have no solid purpose besides “beach.”

Not Allan. His status as the harmless nice guy who doesn’t want anything from Barbie or Ken relieves him of any pressure to do, say or be anything other than Allan. He is both participant and detached observer. Where the other dolls dance to Barbie’s choreography, Allan cheerily lumbers on and off the beat. When he plays the part of the athletic hero – when he’s trying to be like Ken – he’s clumsy, awkward and gets hung up on walls and barricades he’s only equipped to go around.

When he notices his chill wonderland degenerating into a place where all his fellow dudes want to do is rave about “The Godfather” and have their eardrums pounded by Matchbox 20 songs, he reveals himself to be a political outsider. Turns out Allan doesn’t vibe with all that “Kenergy,” so he tries to bounce.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

That doesn’t make Allan soft. When Gloria and her daughter Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt) hit a roadblock to escape a Ken doll junta, Allan pummels the versions of his supposed buddy blocking them. (One takeaway from this is that Scott Pilgrim was also an Allan.) This is an act of desperation and dedication to Barbieland under Barbies, but mainly frustration. Life in the Barbie matriarchy wasn’t entirely equal, but it lacked Ken’s enthusiasm yen for subjugation . . . and horses.

Much is being made of what “Barbie” is versus what it should be, and what it is messaging about feminism or failing to. Its conclusions about self-actualization pull less attention, as is the way of all innocuous, pleasing outcomes.

Barbie realizes she’s taken Ken for granted and encourages him to figure out who he is apart from her – “It’s Barbie, and it’s Ken,” she suggests. Then she realizes she can’t revert to being the doll she’s always been.

Allan continues as he always was – just Allan. There are no multiples. We wouldn’t want him any other way.

Read more

about Barbie-mania