Untangling the deep and troubled roots of democracy can help define its future

Thirty years ago, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, there was a widespread belief that democracy would rapidly spread to envelop the whole world. Now we’re worried about whether democracy can survive, The Varieties of Democracy or V-Dem project, involving thousands of experts, typifies the current focus of the last few decades on what is called the “third wave of autocratization.” But what if something important is being missed by not taking a longer view? A new book co-authored by a group of social scientists and data scientists, “The Deep Roots of Modern Democracy,” argues that there is.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” That famous quotation from Faulkner opens the book, which is ambitious in scope but modest in multiple other ways: It’s mindful of the limitations of available data, open to other possibilities and reluctant to preach. Its fundamental lesson, perhaps, is that democracy today is not the same as it was or as it will be, but its past will always be with us. It is our choice how to understand and interpret that history, and how to use it to create a future. Any informed democratic debate about democracy itself will benefit greatly from the lessons gathered and drawn in this book.

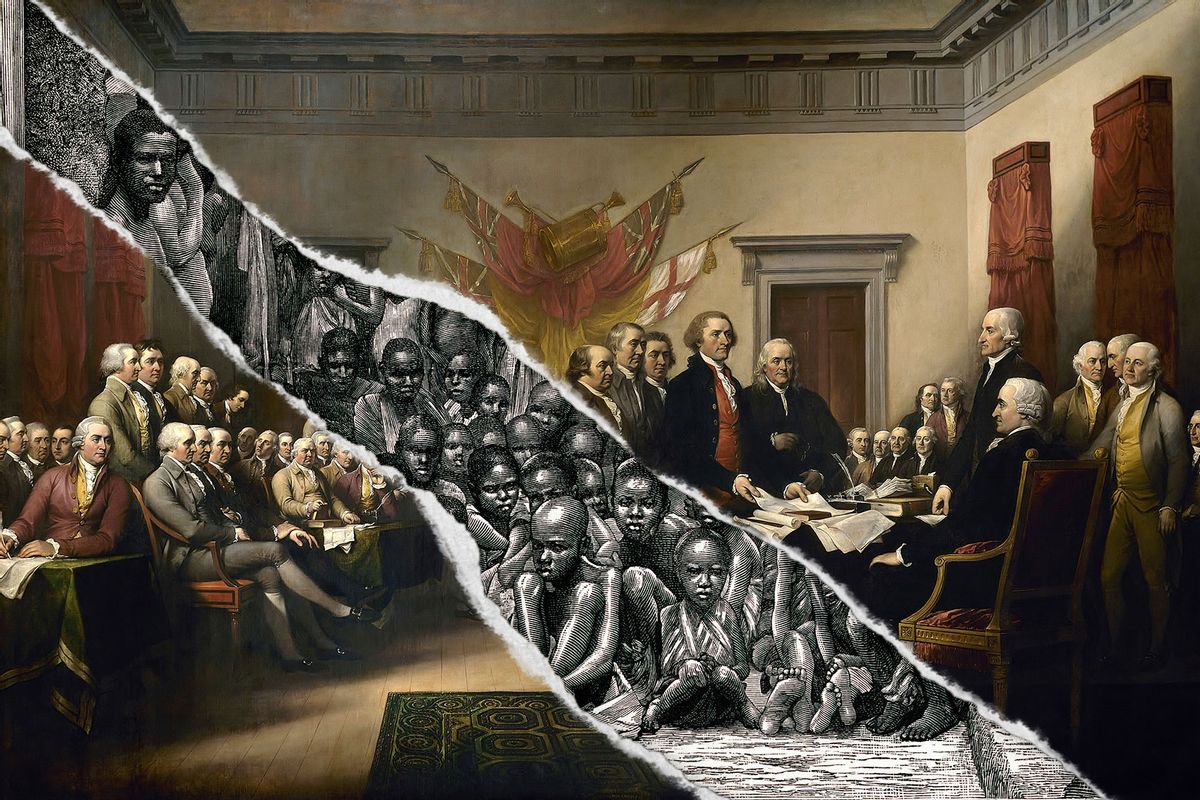

The authors of “Deep Roots” are very much aware of the contradictions embedded in the history of democracy. Direct democracy was common in the pre-modern world, but that isn’t the subject here: The authors identify two principal roots of what they deem modern representative democracy. First is the presence of natural harbors, which facilitate trade and enable open societies. The second is more controversial and requires clear explanation: the proportion of European ancestry in a given society, which reflects the development of representative bodies and major European states, and the subsequent colonial expansion that spread such bodies around the world. To say that the role of European ancestry is complicated is to put it mildly. In many cases, this meant states and societies dominated by colonial settlers — an insider club template of sorts — where the alleged ideals of democracy were compromised by racism and slavery, and where Indigenous populations were largely wiped out or displaced. It’s unacceptably naive to call democracy a gift to the world, given that context. It’s more like a fragile mechanism of political progress that has been unevenly wrestled into something that applies far more broadly than it did at first.

Of course the contradictions at the heart of American democracy are part of a much bigger picture. The combination of quantitative and qualitative data brought together in this book provides an invaluable framework for working through those contradictions we live with still. To explore “The Deep Roots of Democracy” more fully, I recently spoke with lead author John Gerring, a professor of government at the University of Texas, Austin, and a principal investigator at V-Dem. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

There’s been a great deal of attention paid to democratic development, and more recently to democratic backsliding. But your book takes a much longer view. Why did you think that was important?

This is a very hot issue now. There’s an understandable but in some ways obsessive focus on very small changes that have occurred over the past several decades, and that tends to obscure the longer-term continuities. If you look at the countries that were first to democratize, almost without exception they’re the most democratic countries today. And if you look at the number of transitions, there’s been a general trend toward more democracy over the past 200 years. Nobody disagrees over that. But the relative order of different countries does tend to follow this long-established practice, which kind of corroborates our view that in order to understand democracy today, we need to understand its its deep roots.

The title of your book raises two sets of basic questions: First, since democracy is a contested concept, what do you mean by it? And what do you mean by “modern democracy”?

“If you look at the countries that were first to democratize, almost without exception they’re the most democratic countries today. And if you look at the number of transitions, there’s been a general trend toward more democracy over the past 200 years. Nobody disagrees over that.”

Democracy is defined in many different ways. In another project, Varieties of Democracy, we wrestle with that question. In the book, we take the conventional approach in political science, and more broadly on the policy world, which is to focus on multiparty elections as the critical institution in democracy. Other things are reflected in the indices we use, so it’s not just about elections. But elections seem to be at the core of of democracy as it’s realized through representative institutions in the modern era.

That leads to your second question about what we mean by modern. Here we take what I guess historians would regard as a standard definition: things that happened after the French Revolution. That’s the modern era, and that’s also the era in which representative democracy really comes comes to the fore. So there’s a fit, I think between the concept and and the historical era.

OK, and the next question is: What do you mean by “deep roots,” and why do they matter?

In the book, there are these two deep roots, if you will. One is is quite a bit deeper than the other. The first is the existence of natural harbors. We have a methodology by which we identify natural harbors based on the configuration of the coastline, which doesn’t require a lot of artificial construction to dock sizable ships. These parts of the world were more connected to the world in the first place, because they had this readily available technology. It bears emphasis that there really was no way to get around the world aside from ships prior to the advent of airplanes in the mid-20th century. So the role of natural harbors is immense in democracy, we argue.

Any port is a natural point of focus for trade and for migration of people, and for this agglomeration of things that seem to be important for more advanced economies. And so it’s no surprise that a lot of major cities were founded on ports because of their unique access to global or regional markets. In the Mediterranean, that goes back to antiquity. And if you buy the standard story that economic development is propitious for democracy, that pathway is fairly well established.

Then there’s the less obvious point that if you’re a territory with a lot of ocean exposure, you have to develop a strong navy. There’s really no other way that you can retain your access to global trade and also defend against potential incursions, because the port is is your most vulnerable and most valuable site. By contrast, if your territory is located inland or there are no natural ports, your investment in military infrastructure is likely to be centered on a land army. This has all sorts of consequences if you believe, as we do, that a navy is just more propitious for democracy. A land army is a great tool if if you want to stage a coup, if you want to control populations, if you want to have a coercive mechanism to extract taxes and keep people under the thumb of the state. But a navy doesn’t serve well to do that: Your people are at sea, and you don’t have nearly the manpower that you do in a standing army.

Then comes the well-established argument about state-building, which is that cities constrained the growth of states in Europe and elsewhere. Where you have a lot of cities, you’re going to have smaller states. Where you have smaller states, it’s much harder for governments to exercise repression and to control the spread of ideas, and we’re more likely to see the development of institutions at the forefront of representation. So if ports are formed the basis for cities and cities form the basis of small states, at least in the premodern era, then you can see that third pathway from ports to democracy.

The fourth criterion, “openness,” is somewhat more general. It’s easier for immigrants and emigrants to come and go. It’s harder for the state to control the flow of people and capital. If merchants — who are generally the most important players economically, oftentimes as lenders of money to the state — can easily pick up shop and moved to the next court, then they have a lot more bargaining power with rulers. This again builds on a long series of work on European history that suggest that the mobility of capital leads to more open political structures.

You explain in the book how you went about creating models to test that claim. It’s pretty technical but also quite convincing. But what other geographic arguments did you consider? And what did you find?

Good question. To the extent that our arguments are convincing, it really does depend to a large extent on the number of alternative hypotheses being tested. It’s easy to find a correlation, but to determine whether that’s causal or not depends upon measuring all the other things that are geographic in nature and might in some way impact the development of democracy. So we looked at equatorial distance, we looked at whether a region was in the tropics are not, its annual temperature, the number of frost days, the degree of precipitation, the irrigation potential, soil quality, agricultural suitability, caloric variability, the fish that are found there natively on onshore, the degree to which the terrain is rugged and whether or not it’s an island.

Among all of those we found only two that seem to have any promise in terms of predicting democracy in the present: the natural-harbor distance variable and also the distance from the equator. These are independent variables, by the way. They don’t disturb each other’s impact. But distance from the equator is so highly correlated with the share of Europeans in a country that its effect is obliterated or fully mediated by the second factor.

Right, let’s talk about that. You are aware that your argument about European ancestry is complicated and potentially controversial. You make clear that it is not a racial argument, and what was initially spread by Europeans is not what we would call “modern democracy” today. But there is no doubt that there was something different about Europe, and that it was the birthplace of parliaments. Could you start by laying out the argument in broad terms?

This is a familiar argument for those who have followed recent work in economic history and long-term development. There’s a well-known series of articles by a group of economists building on the work of Johnson and Robinson, in which they argue that there is a long-term impact from the colonial era to the present and the impact flows through good institutions. They don’t really measure democracy per se, but we can say that maybe democracy is a good institution. So in some respects we’re following in that tradition of looking at the era of imperialism as a kind of founding moment with long-lasting influence.

“Where Europeans formed a majority, or a substantial minority, they could control the outcome of the democratic process. That allowed them to effectively exclude specific groups of people: Indigenous people, slaves and the descendants of slaves could not vote. Women could not vote.”

There is also a a strand of research that looks at Protestantism, another European import that is supposed to be related. We found some corroborating evidence for that view, that Protestant countries are more democratic in broad and general terms. So we’ve got colonialism and we’ve got Protestantism. Our contribution is to say that, actually, the share of Europeans found in a country turns out to be a better predictor of democracy throughout the modern era than these other things. Of course then you ask about the reasons for this, and the reasons are a little hard to establish.

Here’s the argument we make. For whatever set of reasons — it may have something to do with natural harbors or some other historical conjuncture — this idea of representative democracy was developed first in Europe. I want to be clear that there are lots of examples of direct democracy around the world in the pre-modern era. One might even argue that was the most common method of governance: people getting together in a small group, let’s say tribal leaders, and deciding on what course of action the group wanted to take.

So when we say democracy was invented in Europe, we are referring to one specific form of democracy that involves the selection of representatives through some electoral process. It’s that set of institutions that seems to have been proven useful for governing very large organizations like nation-states. And that’s why it’s come to overshadow direct democracy in our thinking about democracy.

So why did Europeans serve as agents of diffusion for this idea? Well, of course, they came up with it. So they knew what it was about, they knew how to establish it and how to practice it. But it also served their interests, in the sense that where Europeans formed a majority, or a substantial minority, they could control the outcome of the democratic process. That allowed them to coordinate amongst themselves and effectively to exclude people who were in the minority or who were specifically excluded. So Indigenous people, slaves and the descendants of slaves could not vote. Women could not vote, of course. And these exclusions were not unique to to the developing world. They were common in Europe as well.

So where you have neo-European Indigenous populations who were wiped out through disease and conquest and forcible removal, Europeans could establish the same institutions that they were familiar with in this new territory. Where Europeans were minorities, they were, as you can imagine, more circumspect, because establishing democratic institutions that they couldn’t control did not bode well for their for their position in society and would certainly have led to major redistribution of wealth.

You can see in the Caribbean, for example, that British and other settler populations actively resisted independence. They wanted to retain their connection to the metropole because they saw the combination of representative institutions and independence as the death-knell of their preeminence and their control over property. So the argument is that where Europeans predominate you get this strong relationship with democracy, but where they are in the minority you get much less democracy, either because Europeans aren’t interested, and in some cases actively oppose the spread of democracy, or because the idea simply isn’t common and understood the first place.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

So it’s not like democracy was this great gift of civilization, right? At first it was what’s called “Herrenvolk democracy,” with limited or no access to real power for non-Europeans until they managed to secure it, one way or another. That’s a process we’re still in the middle of in the United States, arguably. That may help explain why support for democracy is waning among so-called conservatives like the Trump-era Republican Party. Would you agree?

That’s right. As a general proposition, one can’t think about democracy (or any other political institution, for that matter) as being neutral across all social groups and interests. In the book, we show how democracy was championed by Europeans where they constituted a majority or a sizable minority, such that they could retain the levers of power, because it served their interests. It was European-style democracy designed for Europeans.

One can see this playing out today in the rules for citizenship, voting and other mechanisms that serve to define and delimit participation in democratic politics. And yes, it doesn’t seem too farfetched to see current struggles over ballot access, in which descendants of Europeans resist wider participation by non-European groups, as a continuation of that primordial struggle.

“One can’t think about democracy or any other political institution as being neutral across all social groups and interests. We show how democracy was championed by Europeans where they could retain the levers of power, because it served their interests. It was European-style democracy designed for Europeans.”

So how did you test this hypothesis about the proportion of Europeans and European ancestry in a population?

We had another data-gathering challenge, in some ways much more difficult than measuring natural harbors. We had to collect and collate records from surveys and very early censuses and casual reports from the colonial office reports to estimate the number of Europeans present in all the colonies throughout the world, and subsequently in independent states so we could get a more or less comprehensive measure. That took a long time and we drew from many different sources, but ultimately we were able to put together a data set that reflects a plausible account of the change in the share of Europeans throughout the world from 1600 to the present, with the important caveat that Europeans are being defined by whoever’s taking that survey or census. It’s a malleable category, so we’re really just registering what some researchers would call a constructivist idea of “European”: Who identified as European, and who was allowed to identify as European.

In addition to that, you take a specific qualitative look at the different spheres of colonial influence, most extensively the British Empire. I found that a fascinating supplement to your argument. What was involved there, and what did you find?

That was one of the fun and really interesting parts of the project. We wanted to look at this pre-independence period, and it turned out that there are some data collection efforts that have located the existence of elections or representative assemblies in British colonies in particular. We see a relationship between the number of people from the metropole and the degree to which democracy was allowed to develop. Those parts of the New World with more Europeans within the British Empire, for example, like North America, were more likely to develop and sustain democratic institutions like parliaments, with restricted suffrage of course.

I thought the example of the Caribbean colonies was particularly instructive, because there you have a wide variation in the percentage of Europeans in places with very similar geography.

Yeah. That was that was one of my “aha” moments when you look at the British Caribbean. There are four islands with a substantial share of European settlers, mostly British: the Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands. And those were the only ones that established an elective colonial assembly that was allowed to continue through independence.

You write that these deep causes all appear to have peaked in the mid to late 20th century. Why did that happen, and how does it fit with your theory?

That’s another intriguing part of the story, and it kind of fit with our expectations. If you think about the role of natural harbors, that flows through ships. What good is a harbor without ships? The role of shipping in the international economy has in some ways continued to grow, but as a mechanism of transport shipping has declined since the mid-20th century and has really been eclipsed by the airplane. So the high point of shipping, in terms of its impact on cultures and societies and politics, is probably the middle of the last century. So it wouldn’t be surprising if the relationship between natural harbors and democracy begins to attenuate toward the end of the 20th century.

Likewise, if you think about Europeans as a force in the world, in terms of the spread of their overall geopolitical and cultural influence, that also probably peaked sometime in the mid 20th century. We’re accustomed to saying that Europeans — meaning Europe itself, as well as its transplants, like the majority population in the U.S. — are less dominant, thankfully, than we used to be. So the idea that there would be some attenuation of the correlation of Europeans and forms of democratic political institutions fits with our commonsense view of of the world.

In your last chapter, you advance the idea that connectedness promotes democracy, with four complementary explanations. You summarize that by saying that, collectively, this constitutes a connection between globalization and democracy. What’s the elevator-pitch version of this argument, and how does it relate to your main findings?

This is a very speculative chapter, as many conclusions are. But we conjecture that although the role of harbors and Europeans may be declining, and probably will continue to decline over the course of this century, there may be a more general phenomenon that we can call globalization that has been present throughout the history of democracy and will continue in the future.

“The same institutions, the same technologies, that can allow for the flow of ideas that empowers democracy can also allow for the repression of ideas. Which way this is going to go is something I don’t know the answer to.”

If you think about democracy as depending on the free flow of ideas and people, insofar as people and ideas and capital can move across borders, and that this in some way reinforces democracy and constrains the power of leaders, well, this is a phenomenon that in some ways we’re experiencing now. The caveats here are important, because the same institutions, the same technologies, that can allow for the flow of ideas can also allow for the repression of ideas. And which way this is going to go is something that I don’t know the answer to. But I think it will be critical to the future of democracy. If we think about the internet as a tool of free expression or of surveillance, who’s going to win that technological war?

The last chapter does seem to offer grounds for optimism, as you just said. But representative democracies have been suffering recently, and I wonder how much you’ve thought about proposed countermeasures, such as citizens’ assemblies (Salon story here), or other innovative developments that you think might evolve.

This is a head-scratchier, because everyone can see that the seemingly inexorable rise of democracy has at best taken a pause. The institutions of representative democracy that people in my field of political science were uniformly optimistic about a couple of decades ago have now led to some consternation. We’re seeing these same institutions used as tools for populist leaders with rather antidemocratic agendas. So, does democracy contain the seeds of its own destruction? That is the question we have to be asking ourselves.

I’m not necessarily meaning to portray a pessimistic narrative, but the fact that we’re having this conversation at all indicates that maybe we need some kind of reboot, maybe we need to consider alternatives to these long-established institutions. I can’t say too much about these kind of deliberative assemblies, the James Fishkin model of democracy (Salon stories here). I know about that, but I haven’t studied it, and I am a little dubious about how much legitimacy these assemblies might have. Are ordinary citizens going to regard their decisions as more legitimate, let’s say, then the elected assembly? I think that’s the crucial question, because governance by lot does have something to recommended it, but only if people believe that they’re a source of authority.

Other than that, I think we do need to do some collective head-scratching. I think there may be some improvements that we haven’t come across or haven’t tried or haven’t been given a fair chance, and that those need to be considered.

Read more

from Paul Rosenberg on democracy and history