Why criminalization of drugs doesn’t prevent overdoses

For more than a decade, the United States has been rocked by a record-breaking overdose epidemic. Over 100,000 Americans are losing their lives to preventable drug overdose each year.

Many state legislatures are attempting to stem this tide by criminalizing new substances and increasing penalties for drug crimes and classifying overdose death as homicide. For decades, the War on Drugs has been our most widely supported policy response to substance use. But what if this approach causes more harm than good? That’s what our new research suggests.

My colleagues and I set out to explore the correlation between drug seizures by Indianapolis Municipal Police and overdose in the surrounding community. Our new report, published in the American Journal of Public Health, provides strong evidence that law enforcement intervention is not just ineffective but counterproductive in preventing overdose.

Using two years of administrative data from Marion County, we compared the time and location of drug seizures logged by local police to clusters of fatal overdoses, nonfatal overdoses, and naloxone administrations by first responders. If seizing illegal drugs protected public health, we would expect overdose rates to decline after each seizure.

But, in the days immediately following an opioid drug seizure, within a few hundred meters of that seizure, overdoses doubled.

In the days immediately following an opioid drug seizure, overdoses doubled

Many mistakenly perceive illicit drugs to be deadly because they are so potent. In truth, illicit drugs — especially opioids — are so risky because there is little room for error. A minor mis-dosing could have life-threatening consequences. Fluctuations in the illicit drug supply increase the likelihood of a mis-judged dose.

Previous research demonstrates how drug seizures expose people to an unpredictable supply. People who sell drugs have to alter their supply to meet steady demand with less product than they had before. People who use drugs may have to seek different products from unfamiliar suppliers if their trusted source is unavailable or their drugs are suddenly taken away. The impacts of even small disruptions can spiral quickly out of control. We have entire federal agencies whose sole purpose is to pursue that disruption.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

For years, my colleagues and I have heard the same refrain from public health professionals, first responders, and people who use drugs: drug interdiction drives overdose. Our research provides the most damning evidence to date that this growing consensus is correct: criminalization creates many of the harms we associate with substance use, harms which are then leveraged to justify harsher criminal responses.

It is critical that policymakers understand the implications of this growing body of research. While the War on Drugs might be “status-quo,” it is becoming increasingly clear that they are not effective mechanisms for protecting public safety and could actually increase overdose risk.

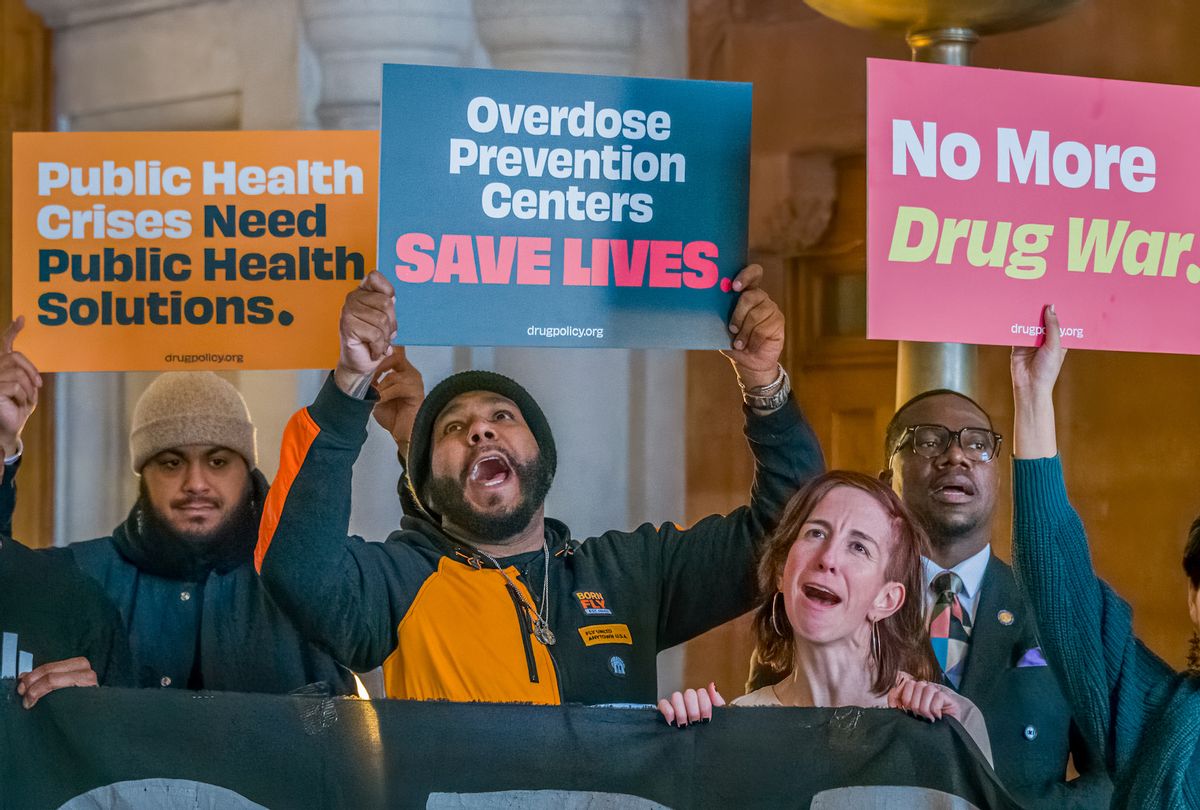

So, what can we do? We can start by making gold-standard addiction treatments more accessible and channeling public dollars into low-barrier, affordable housing. We can invest in proven, compassionate and community-oriented solutions to reduce overdose, like drug checking, syringe services programs and overdose prevention centers. Decades of research show that these programs (including the two overdose prevention centers in New York City) are far more effective at saving lives and linking people with health care services and addiction treatment than any other program model we’ve tried in the United States.

Our research provides the most damning evidence to date that criminalization creates many of the harms we associate with substance use, harms which are then leveraged to justify harsher criminal responses

We can ensure that naloxone, the opioid overdose antidote, gets into the hands of people who use drugs by supplying it to harm reduction programs. Additionally, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration can take steps to extend over-the-counter designation to generic intramuscular naloxone — the most common and the cheapest form of this life-saving medication.

Moreover, we can take a long, hard look at what drug prohibition has truly delivered. Our study demonstrates a strong correlation between drug seizures and overdoses in the following days, but other troubling findings suggest that any criminal justice response, from arrest to incarceration, drives up overdose risk.

And what about drug-induced homicide? These laws are ostensibly enforced to honor those who have lost their lives to overdose. Could treating overdose deaths like homicides also cause more overdose? Research already suggests that it does.

We deserve solutions that work. And we know what works. We need leaders to make those solutions a reality.

Read more

about drug policy