A new model for human origins in Africa upends commonly held beliefs about our evolution

Many of us learned in high school that our human ancestors first evolved in Africa before slowly spreading out across the planet. But that may not be the full story.

New research published in Nature in May aimed to shed new light on human origins in Africa and beyond. An international research team using sophisticated computer software and a large set of genomic data — including DNA from many different populations in Africa — tested a variety of models for how human populations arose and diverged, producing the genetic variation we see on the African continent today.

The best-fitting model they found may well force changes in the story taught about human evolution. Salon spoke with two of the study authors, who say that while there’s enthusiasm from some scientists, others seem a little confused.

“On the one hand, the human geneticists, even though this overturns a lot of prior models, at some level, I think they think it’s exciting,” Dr. Brenna Henn, a population geneticist at UC Davis, told Salon in a video call. “But maybe they don’t quite know what to do with it.”

In place of a tree, we see a pattern of diversion from migration and reconnection through interbreeding, a bit like the veins in a leaf.

If you’ve ever looked up your family genealogy, you’re familiar with the main ‘prior model’ being overturned: it’s that upside-down tree shape. In this case, the tree described how our very large family — modern humans — were thought to arise from a single source region somewhere in Africa. The new research, by Henn, Simon Gravel and others, supports previous findings that began to undermine this idea. Perhaps most intriguingly, the new analysis points to a complex ‘weakly structured stem’ shape of divergence and coalescence that better explains the genetic data and diversity in the fossil record.

The new model begins at the Middle Pleistocene, approximately one million years ago, when there were not one but two main populations of humans. But instead of developing completely separately, gene flow continued between the groups over time. In place of a tree, we see a pattern of diversion from migration and reconnection through interbreeding, a bit like the veins in a leaf. Two distinct veins (or stems 1 and 2) remained weakly genetically connected through tens of thousands of years.

Around 120,000 years ago, a merger event between populations descending from stem 1 and stem 2 gave rise to the modern day Nama people, a group of hunter-gatherers who populate South Africa, Namibia and Botswana. Not long afterwards, a different population of stem 1 descendents merged with a stem 2 population, resulting in the ancestors of Eastern and Western African populations — and everybody else outside Africa.

In an interview with Salon, Sriram Sankararaman, an associate professor in UCLA’s Departments of Computer Science, Human Genetics and Computational Medicine, praised the research team’s thorough exploration of possible models and use of rich, diverse data sets. But he doubts this is the end of the story.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“The resulting complexity of the model means that it’s difficult to say exactly how closely it reflects reality,” Sankararaman, who was not involved with the Nature study, said. “Given these models are so complicated, it’s probably a reasonable thing to assume that the true models are going to be even more complicated than anything they say so far.”

One aspect is the question of exactly whose genes are involved in all this gene flow. To explain the genetic diversity of modern groups in Africa, population geneticists have thought that ancient hominins (our now-extinct relations) might have contributed their DNA to populations that led to modern humans, as occurred in Europe, Asia and Oceania. There, significant good research shows human populations who had migrated out of Africa had sex, producing cute hairy babies at various times with two of our ancient relations, the Neanderthals and the Denisovans.

“Given these models are so complicated, it’s probably a reasonable thing to assume that the true models are going to be even more complicated than anything they say so far.”

This has left many of us with a little Neanderthal genetic material to this day. In non-African populations, it’s about two percent, though that number has shrunk over the years, as bits of DNA that damaged our health or fertility were weeded out. From what Dr. Sankararaman’s research suggests, it was once about three percent of the human genome, which is not an insignificant amount.

But in Africa there isn’t much evidence of such an “archaic admixture.” There’s some, but it’s not definitive.

“There’s one particular stem which predates the split of Neanderthals from the ancestors of modern humans. And then the stem again mixes with the modern human lineage,” Dr. Sankararaman said. “There’s this deep population structure that is contributing to the gene pool in Africa … The question of whether this is truly archaic or not. In my mind, it’s not completely settled.”

The researchers argue that their model, in which gene flow persisted despite divergent populations, better explains genetic diversity across the continent. It’s also possible, as they concede, that further research by geneticists might still favor a hybrid explanation, in which there was some admixture from archaic hominin genes as well as the connections among populations they describe.

They say some scientists whose focus is on interpreting the fossil record have been pleased to see genetic analysis bear out what they already knew.

For example, the 2017 discovery of skull fragments, a jawbone and stone tools in North Africa, dating back approximately 315,000 years, upset previous ideas that Homo sapiens evolved from a single population in East Africa. Previous assumptions were based on two skulls found in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley,both of which were about 195,000 years old.

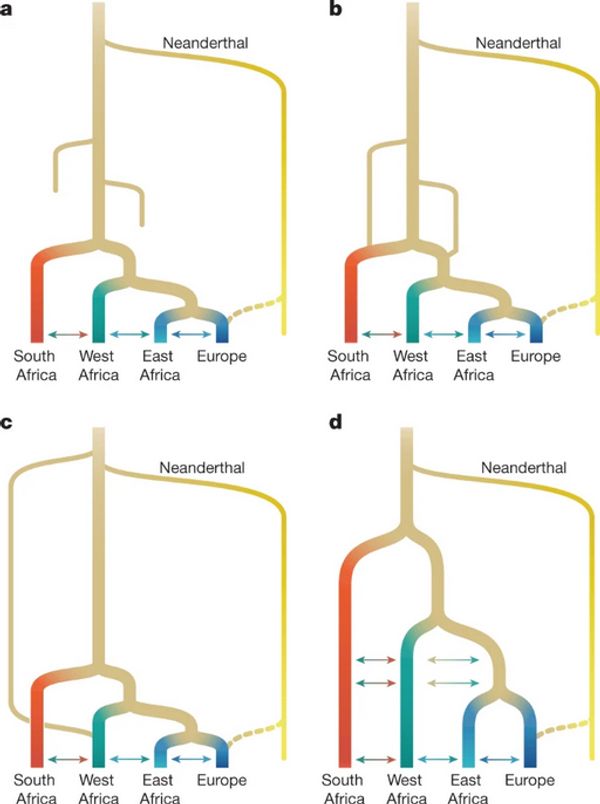

a, Recent expansion. b, Recent expansion with regional persistence. c, Archaic admixture. d, African multiregional. The models have been designed to translate models from the palaeoanthropological literature into genetically testable demographic models (ref. 1 and Supplementary Information section 3). These parameters were then fitted to genetic data.

a, Recent expansion. b, Recent expansion with regional persistence. c, Archaic admixture. d, African multiregional. The models have been designed to translate models from the palaeoanthropological literature into genetically testable demographic models (ref. 1 and Supplementary Information section 3). These parameters were then fitted to genetic data.

“I think the fact that we have fossils that we classify [as] somewhat sapiens that are found fairly early in multiple regions in Africa would be consistent with [our] model,” Dr. Tim Weaver, another of the study authors and an anthropologist himself, explained to Salon. “The fact that we find them in various places, that’s probably more consistent with this. And that’s a piece of evidence that people had used to try to argue for this model before our paper came out.”

On the other hand, some paleoarcheologists are very committed to the single origin idea, each arguing for the primacy of their fossil evidence for a single origin in either southern Africa, East Africa, or North Africa.

“I feel like we’re a bit of an empirical bunch,” said Henn of her population geneticist peers. “Like, ‘okay, well, the paper says this, so I’m going to update my beliefs’. And I think with the paleoanthropologists and archeologists, this may be a little bit of a different situation.”

This is a tart reference to what this paper’s authors call “model misspecification.” In essence, this is becoming set on one or two simple models and then trying to fit the data to them. In fact, the research team sees this as their most important argument: that it’s important to expand not just the data scientists study, but the range and complexity of models they test for the best fit with that data.

“Part of the philosophical exercise in this paper,” Henn explained, “was to say: ‘Let’s pretend we know nothing. How can we come up with creative ways to imagine what’s going on on the African landscape 500,000 years ago that have not been represented?'”

Read more

about human evolution