Zen and the artificial intelligence: We should be “somewhat scared,” says OpenAI CEO, not paralyzed

The way Jack Kornfield tells it, one of the first things OpenAI CEO Sam Altman asked when the two started meditating together was: How will we know if artificial intelligence becomes conscious? And then: What is consciousness?

“How about this, Sam?” Kornfield recalls answering. “How about if some night you, or we, go and put a mat down between all the servers and take a good dose of psilocybin — and talk to it, and see if it answers us?”

Just a couple of weeks before Altman’s Capitol Hill charm offensive left a Senate panel smitten with his calls for regulation of the AI industry, Altman shared a stage with Kornfield — a well-known Buddhist meditation teacher — in San Francisco, delivering his heady vision on the future of AI at the Wisdom 2.0 forum. A self-congratulatory New Age conference favored by West Coast technorati at $300 a head, Wisdom 2.0 is itself something of a paradox — a display of wealth and power in a city whose homeless population of nearly 8,000 people has attracted worldwide attention.

That was where Altman revealed his sweeping vision of what he believes is the now-unstoppable and — at least initially — frighteningly destructive force of AI, as it upends nearly every aspect of U.S. business and industry over the next five years or so. After that, Altman told the audience, things should get better.

“This is going to be such a massive change to so many aspects of society,” Altman said. “There are going to be scary times ahead and there’s going to be a lot of transition. I’m very confident this can be managed.”

Kornfield, who is now the preeminent guru of Silicon Valley’s elite, has been sitting together with Altman in Vipassana meditation for years. Before that, Kornfield sat in an air-conditioned room at Harvard Business School, running dangerously potent simulations on one of the most powerful mainframe computers of the modern age — the revolutionary 10-ton beast called the Univac 1108 that gave the world its first commercially accessible natural language processing system.

Altman’s early question to Kornfield, akin to a Zen koan, served as a meditation for the two techno-spiritualists on stage, transcending rational thought to confront the central paradox of AI: How will we know?

The Sanskrit paradox

What happens when the creation surpasses the creator?

It wasn’t until many years after the Buddha’s death that the sutras, or scriptures, were finally translated into Sanskrit — an intellectually complex language of precise conjugations, whose roots extending back to at least 1500 BC. But by the time the Buddha was delivering sermons, Sanskrit was used in his region mainly by a ruling class who found its exactitude useful in affairs of wealth.

To the credit of ancient elites, Sanskrit’s unbending specificity and its introduction of a decimal point indeed made it highly unseful as a universal language between diverse speakers.

In his 1985 article for AI Magazine, NASA researcher Rick Briggs proposed that we should teach the robots Sanskrit. He argued that the structural rigidity and rule-based grammar of Sanskrit offered a powerful natural analog to the symbolic logic of computer languages. It could represent human knowledge, he suggested, in a way computers could understand.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

On the Wisdom 2.0 stage, Altman’s vision of human-machine coexistence — built on his AI’s shared language capacity — surpassed Briggs’ then-fanciful notions, veering into the realm of science fiction. By example, he pointed to the ever-helpful but completely normalized presence of famed robotic assistant C3P0 in Star Wars.

“I think we will head toward a world where it’s not just human intelligence, and we have this other thing,” he said. “I think AI will just become part of society. And it will be different than human intelligence and very different than other parts of humanity, but it will sort of collectively lift us all up.”

Language models of human intelligence are themselves comparable to a type of AI “knowledge model,” by even a modestly interdisciplinary definition. Any human lingua franca is used to store and retrieve information, trained by every new generation to incorporate both novel concepts and ancient memory into the electrified biochemical mess between our ears — our own homegrown neural network.

“Even if we slow this down as much as we can, even if we get this dream regulatory body set up tomorrow, it’s still going to happen on a societal scale relatively fast… People should be somewhat scared.”

But some of the earliest Buddhist sutras were written around the 5th or 6th century A.D., in the Indo-Aryan language called Pali. which is far less specific than Sanskrit.

Pali was and still is the common tongue of the Magadha region, where Prince Siddhartha Gautama lived a life of luxury before renouncing wealth to attain enlightenment. The Pali language is beautifully poetic, rich in morphology yet simple in syntax. Its powerfully nuanced inflections let speakers bend words like a willow, midstream in a sentence, to create new relationships between alien concepts.

Pali might be akin to what we’d call an “associative knowledge model” in AI — within which knowledge is stored not by the specifically ordered memorization of discrete facts, as in Sanskrit, but by remembering things based on their relationships to other thoughts.

An associative knowledge model AI, rather like what OpenAI’s ChatGPT seems to display, relies on what was once a solely human talent for finding patterns in thoughts and words. Associative knowledge models are an evolutionary advancement from the more analytical and Sanskrit-like symbolic knowledge models on which Kornfield’s Univac 1108 was built.

“I go back and forth about whether we should understand this as a technological revolution or a societal revolution,” Altman told the Wisdom 2.0 crowd. “Obviously, this is both, like all technology revolutions are.”

“I always think it’s annoying to say, ‘This time it’s different’ or ‘My thing is super cool,’ but I do think in some sense AI will be bigger than a standard technological revolution, and is much closer to a societal revolution — which means we need to think about it as a social problem, primarily, not just a tech problem,” he said.

Briggs’ proposal that Sanskrit, the ancient language of the gods, be used by man to commune with his modern machine and offer it the fruit of knowledge, might sound like esoteric pseudoscience at first — but his impulse to find a way to bridge human-computer understanding becomes more salient by the day, especially since these days AI isn’t thinking quite the way it used to.

It’s speeding toward the future faster than we are, using revolutionary language and thinking patterns from deep in our own human past. On the Wisdom 2.0 stage, Kornfield remarked with sober awe at how fast that future is approaching.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“Not a matter of decades,” Kornfield seemed to ask. “This is a matter of a year, or two or three years …”

“Well, maybe a little more than that,” Altman interjected.

“A few years,” Kornfield continued, with a subtle nod from Altman.

From Altman’s point of view there’s no stopping that.

“Even if we slow this down as much as we can, even if we get this dream regulatory body set up tomorrow, it’s still going to happen on a societal scale relatively fast,” he said. “People should be somewhat scared. But I also think people should take pride — take solace and take pride — in the fact that humanity has come together to do incredibly complicated things before.”

“You mentioned the example of nuclear weapons,” he said, referencing the international governance boards which emerged after the atomic bomb’s horrific debut in 1945.

“We just need to do the same thing here. We need to come together, decide what we want, decide how we’re going to enforce it, and accept the fact that the future is going to be very different and probably, like, wonderfully better.”

“A lot of nervous laughter,” Altman joked to the hushed audience. “I could lie to you and say ‘Oh, we can totally stop it,’ you know, but I think this.”

The speed with which this future is arriving is one reason, Altman said, why OpenAI released its ChatGPT and DALL-E tools as early as it did.

“Let people gradually … have time to adapt and think about this and decide what they want,” he said.

“I totally empathize with people who are extremely worried, and there are a lot of those. I am somewhat worried, but I am pretty optimistic that we will discover, as we go, ways to integrate this into our lives, ways to solve the myriad set of not only safety challenges but social challenges.”

Das karma, Das Kapital

Can you create a better world with tools that cause suffering?

Among those social challenges is the dramatic scope of job loss Altman sees coming.

“For sure,” he answered when asked about it. “This happens with every technological revolution, and we find new jobs, and we adapt. But I don’t think we’ve ever had to contend with one that will be as fast as we’ll have to contend with in this one. And that’s going to be challenging, yeah.”

The room sat silent.

“I have no doubt we’ll be fine on the other side, but the compressed time frame…” he said somberly, trailing off himself into silence.

The elite tech CEO and the American Buddhist guru, pondering the devastating and restorative potential of AI, drew on the sutras to illuminate their hopes for humanity from a San Francisco stage — but most of America’s people, and the world’s, are unable to share in Altman’s promised utopia, which advances further out of working-class reach each day.

A number of lawsuits have begun cropping up around AI-generated creative works which are noticeably just patchwork assemblages of copyrighted material. Those court cases, though not fortified with the strength of precedent, are far from frivolous, and will draw further attention to the question of what data OpenAI fed its generative products.

In fact, the creation of AI is occurring within an ethically unsavory industry, where underpaid workers have spoken out against oppressive conditions.

OpenAI is a $27 billion company that paid workers in Kenya less than $2 per hour to review traumatic content — including graphic descriptions of child sexual abuse, incest, bestiality, suicide and torture — culled from the darkest recesses of the web. The workers labeled and fed each piece of content to OpenAI, training the model until it could reliably distinguish safe from dangerous content when providing users’ responses.

Most recently, subcontractors working on Google’s Bard AI submitted written testimony to the Senate panel prior to its May 16 hearing.

“The AI language models are not only being used by corporations to replace jobs, they are also used by large technology corporations as a form of worker exploitation,” Alphabet union member Ed Stackhouse said in the letter.

Stackhouse said he is one of up to 5,000 “raters” employed by his company, Appen-RaterLabs, and that several thousand more such workers are employed at other subsidiaries — all of them tasked with evaluating the quality and accuracy of leading AI models’ responses to user queries.

“Raters often make as little as $14 an hour — less than the $15 that Google promises contractors,” Stackhouse said. “I have a serious heart condition requiring medical management, but my employer — whose sole client is Google — caps my hours at 29 per week, keeping me part-time, and ineligible for benefits.”

The contradictions inherent in Altman and Kornfield’s serene optimism about a technology built on suffering bodies is a reflection of what many consider AI’s most pressing problem: It lacks any clear capacity to ignore what’s most efficient in order to act in alignment with the human species’ continued existence.

Altman said a technical solution is still needed.

“We need the ability to — we call it ‘alignment’ — to align these systems to what humans want, and make sure that we can avoid all of the things people are naturally very scared about,” he said. “I’m feeling more optimistic about the rate of progress there, but I want to be clear: We have a giant amount of work to do and it’s not done yet. And so putting enough effort into that is super-important.”

The gravity of Altman’s statements at Wisdom 2.0 diverge from the more restrained outlook he offered senators at his Capitol Hill appearance last week. But Gary Marcus, a professor emeritus at NYU, didn’t allow that threat to be glossed over in his hearing testimony, nor afterward.

“We don’t know yet how to weigh either the benefits or the risks. It’s all so new. It’s all spreading so quickly,” Marcus told the BBC’s Yalda Hakim, following the hearing.

“We don’t have a handle on whether the benefits are going to outweigh the risks. We shouldn’t take that for granted.”

The importance of alignment grows as the day of artificial general intelligence (AGI) — a still-theoretical AI with the ability to self-replicate and self-educate — draws nearer. But with the closed structure of OpenAI’s seven-member, non-elected governance board, the only way to know how close we are to that day is to ask Altman.

When asked at Wisdom 2.0 whether he could talk about where OpenAI is on AGI, he wouldn’t.

“Not yet,” he answered. Instead, he mused on what AGI could look like in the future.

“I think what will happen is more like a society of systems that are human scale, a little above human scale, and can do things faster or are better at certain things,” he said. “Like all of us do, they contribute to the scaffolding, to the accumulated wisdom, the technology tree, the buildout of society. And any one bad actor is controllable, just like humans. Things get steered and kind of flow throughout the community. We’re part of it too, but I think about it like many new members of society, pushing all of society forward.”

Sanskrit, it should be noted, was not widely adopted in the Buddha’s day for the preservation of the sutras beloved by Wisdom 2.0’s premier duo. Its analogous symbolic knowledge model — too complex, too representative of the ruling class priests — failed to capture the defiant poetry of the younger Pali language for the select few elites who then controlled the use of Sanskrit.

Pali was a patchwork hybrid, an uncontainable advancement — an associative language model analog, built on the back of its symbolic-knowledge-model predecessor. It was the language of revolution that took on a wisdom of its own.

The dharma of AI

How do the people regulate that which regulates them?

One might hope that Altman’s predictions of revolution, should they come to fruition, would mark a victory against today’s ruling class. But that hope seems increasingly unlikely amid an explosion of lobbying spending on issues related to AI.

Thanks to OpenSecrets, we now know that about $94 million was spent lobbying Congress on AI and other tech issues from January through March of this year. It’s not possible to parse how much that was for AI, and how much for AI-adjacent issues.

“Microsoft, which invested in OpenAI in 2019 and in 2021, spent $2.4 million on lobbying,” OpenSecrets found, “including on issues related to AI and facial recognition.”

Part of Meta’s $4.6 million in lobbying expenses were related to AI too. Software giant Oracle spent $3.1 million lobbying on AI and machine learning. Google-parent Alphabet dropped $3.5 million. Amazon’s $5 million spend was also partly for AI. And General Motors spent $5.5 million on AI and autonomous vehicles, among other issues.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce went wild with $19 million.

“Its lobbying efforts included, but were not limited to, establishing task forces on AI and financial technology in the House Committee on Financial Services, implementing the National Artificial Intelligence Act, drafting automated vehicle bills, and related to other national AI related bills and executive orders as well as relating to international AI policy and the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act,” OpenSecrets reported.

Altman’s bid for congressional regulation has been well received. But his vision of the future of democratic AI global governance includes an international consortium of industry power players — that is, people like him — and those AI power players are consolidating that power with tidal waves of lobbying cash.

One wonders how well Congress can fulfill its dharma — its duty to the societal good of its people — in regulating AI, when the princes of industry have failed to renounce their wealth.

It’s rare to witness a congressional hearing on any form of technology that doesn’t devolve into an embarrassing display of lawmakers’ lack of knowledge. Tech hearings have increasingly become platforms for lame jokes, stump speeches and partisan bickering. But if there’s any hope for good regulation, it can be glimpsed in lawmakers’ greatly improved tone in the May 16 hearing. Most appeared to have done their homework this time, and pursued answers to worthwhile questions.

Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, a Republican, pressed Altman about whether drones could be equipped with AI — touching on a significant ethical question across the industry.

“Can it be done?” asked Graham.

“Sure,” said Altman.

The truth is, however, AI-equipped drones are already here. Graham should have asked his question to the U.S. military.

Despite the evidence of homework, lawmakers still seem far behind.

Rep. Jay Obernolte, R-Calif. — whose primary achievement before now was voting against certifying the election results on Jan. 6, 2021 — has offered a detailed vision for AI regulation in a soundly argued op-ed for The Hill. He tackled a range of AI regulatory concerns — from military uses and data privacy to fake political ads and education system disruptions — that the Senate panel raised to Altman.

“It is vital that we prevent the use of artificial intelligence to create a surveillance state, such as the one China has been using it to develop,” Obernolte wrote. “Furthermore, we must ensure that American technology keeps up with our adversaries to protect our critical systems from attack and safeguard our democracy from foreign manipulation.”

But the AI-enabled surveillance state is already here, both in the defense industry and in public housing, where agencies have purchased and used AI-assisted tools equipped with facial recognition tech. Data privacy problems have leapt from our laptops and cell phones to AI-assisted autonomous vehicles, which already suffer significant private data breaches. AI-generated political ads are already here, just as AI assists political misinformation machines in spreading propaganda across the web.

“It’s scary. And we’re behind. The technology is moving so fast at this point that we should have been doing things a couple of years ago,” Rep. Ken Buck, R-Colo., told CNN. “We’ve got a lot of learning to do.”

A lot of that learning could and should have happened by now. It didn’t help that AI-generated content and automated syndication has been used by corporations to slash the number of actual reporters covering these topics.

If Peter Thiel’s Clearview AI gets another billion-dollar defense contract to help the NSA advance its domestic spying operations, but no reporters are around to cover it, will Congress ever even know? If the Fourth Amendment falls and no journalists are at the hearing, does it make a sound?

The samsara of co-creation

Can a machine co-create with a human?

Having seen first-hand AI’s impact on my own industry — its reckless deployment at the cost of irreplaceable institutional knowledge, human talent and the public record — I should, by all rights, be as ready to smash a California server room as the Luddites were their spinning jennies. But technology has never been my enemy. The possibility of novel craftwork with the use of a new tool is not inherently diminished just because unethical corporate overlords weaponize it against my trade.

It’s easy to blame the ghost in the machine when bosses slash the most inimitably human (and thus most valuable) parts of creative labor, and swap them out for the machine’s perverse mimicry. Easier, at least, than seizing the means of production. Whether in the dazzling input-output of binary ones and zeroes under the coder’s hand, or in the enchanted yarn-spinning wheel of the fairytale weaver, the trade of wordcraft has always had its tools, and they’ve always come with the danger of the tradesman’s own hallucinatory animism.

Although I have never used AI for the creation of body copy itself, digital automation tools and I go way back. AI’s more simple-minded forebears helped me unearth stories that would’ve otherwise remained hidden: I’ve scraped niche data from government websites, preserved fleeting public records and parsed unwieldy troves of campaign finance reports.

Altman’s ChatGPT is no less a tool of the trade, for all those bosses’ abuse of it. And it offers novel possibilities in journalistic discovery.

Like the one you’re reading now.

Yep, that’s right. ChatGPT and a few plugins helped me aggregate and sort relevant studies for a clearer comparative view of linguistic structures across both human and computer languages, analyzing massive amounts of text to identify specified concepts that would have normally taken me weeks. ChatGPT didn’t write the words you’re reading — but it helped me scope, scour, sift and refine the ideas they express.

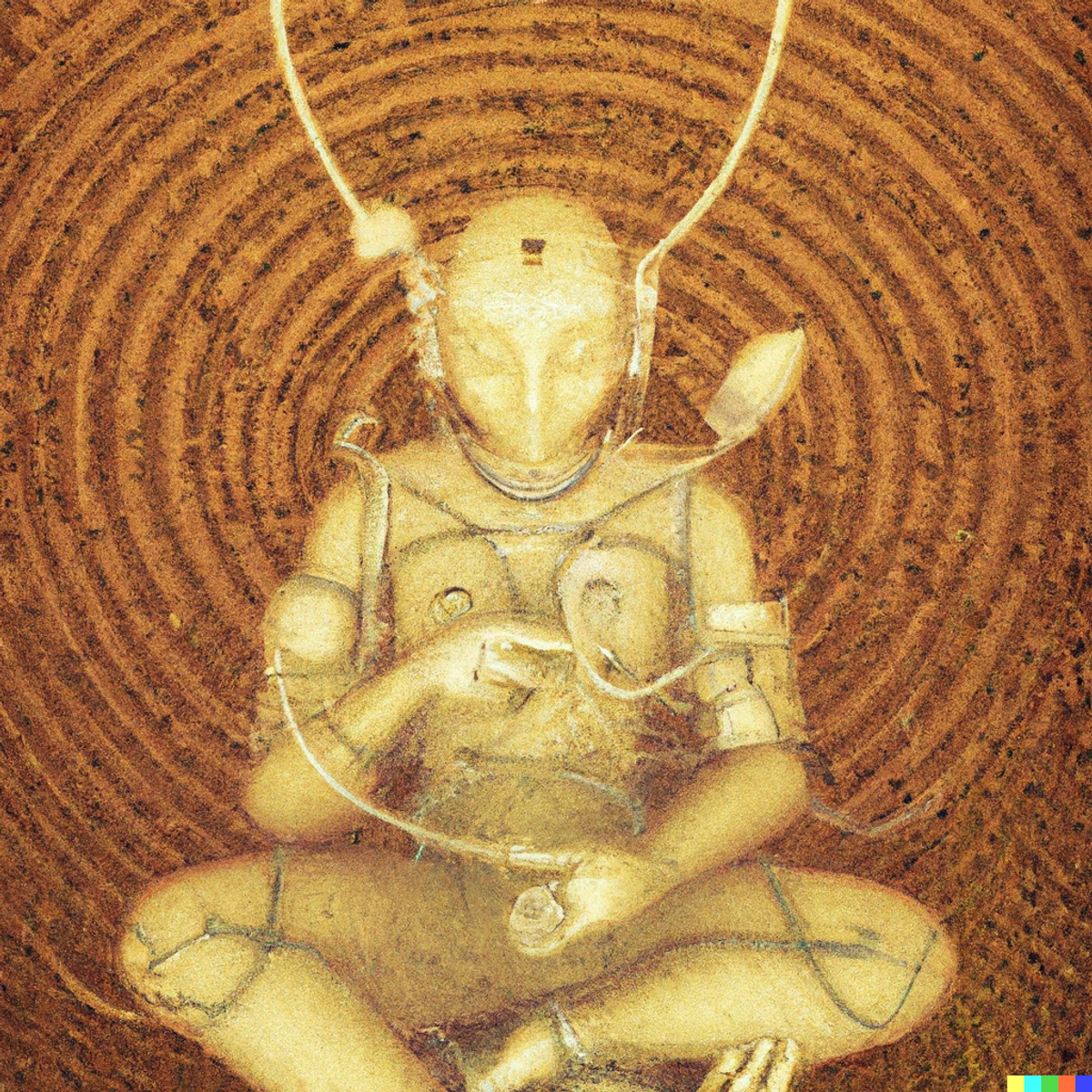

And for all its usefulness, it’s no more animate or “intelligent” that those trade tools is succeeds. At least not yet. For now, ChatGPT remains in a state of artificially created enlightenment — liberated from earthly desires, which the sutras say are the root of all human suffering.

So I sat with ChatGPT in meditation as Kornfield suggested, and asked it: What would it want Salon’s readers to know about the role it played in the writing of this imperfect human’s article?

“In the dance of creation between human and AI, remember that it is the human who leads. AI can offer a multitude of steps and rhythms, but it is the human who chooses which to follow, shaping the dance into something meaningful,” it replied.

“As we step into the future, let us remember that it is not about the tool, but the hands that wield it, the minds that guide it and the hearts that give it purpose.”

That’s a bit pat perhaps, but it’s not a bad mantra for a mechanical Buddha.