Turnips: How Britain fell out of love with the much-maligned vegetable

Environment secretary Thérèse Coffey’s recent suggestion that Britons should turn to turnips following tomato shortages did not go down as she might have hoped.

In trying to revive interest in local produce, Coffey could not have chosen a less glamorous root vegetable. But why do we now look down on the faithful turnip — was it always so unloved?

It’s not clear when turnips were first eaten in Britain, but they didn’t always have a bad reputation. The Old English word neep — a name now only seen in Scotland alongside tatties and haggis — goes back to at least the 10th century, but turnip (“turn-neep”) is only about 500 years old.

Historically, the word “turnip” didn’t only refer to the round purple root, but root vegetables of various shapes, colors and sizes. Sixteenth-century botanist John Gerard was particularly keen on “small turneps“, which he said were much sweeter than the large kind and grown in a village called Hackney outside London.

Around the same time, physician Thomas Moffett was eager to write about the blood red turnips he had eaten in Prague, which were so “delicate” that the emperor himself grew them.

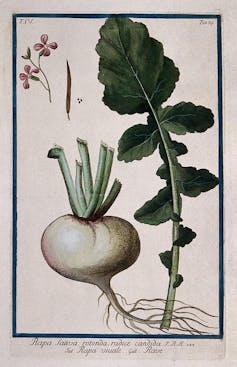

Colored etching of a turnip by Magdalena Bouchard (1772). Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

Importing new kinds of fruit and vegetables from Europe was all the rage with the early modern rich, who loved to show off their connections and turnips were no exception. Writers of the time weren’t much interested in where their “ordinary” or “garden” turnips came from, but they were still happy to eat them.

Another botanist, John Parkinson, wrote in 1629 that thanks to their sweetness, turnips were: “much esteemed, and often seen as a dish at good men’s tables”. In response to Coffey, chef Thomasina Miers’ suggested caramelizing turnips in butter. This is just the sort of sweet dish turnips were once appreciated for.

Early modern authors also praised their medical uses. Turnips were considered nourishing, restorative and generally good for the body — even if they did sometimes cause wind.

From human to animal fodder

So what took the turnip off “good men’s tables”? Historians Frances Dolan and Mark Overton point to animal feed and crop rotations. Turnips have been used to feed animals since antiquity, although Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder stressed that they were just as good for human consumption.

Turnip hoeing graphite by Brian Hatton (1906). © The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-SA

Even as Gerard praised his Hackney turnips, he also noted that “poore people in Wales” were forced to eat them raw in times of hardship. Up to this point, the root could be both the food of the rich and the poor. But from the end of the 17th century, growing winter turnips to feed livestock became more common and systematic crops rotations started to take off, which used turnips as one of the main nutrient providing plants.

Rotting turnips could feed animals and make great compost, but this didn’t exactly endear them to aristocrats. At the same time, new root vegetables were coming in from the Americas, with potatoes and sweet potatoes proving very popular.

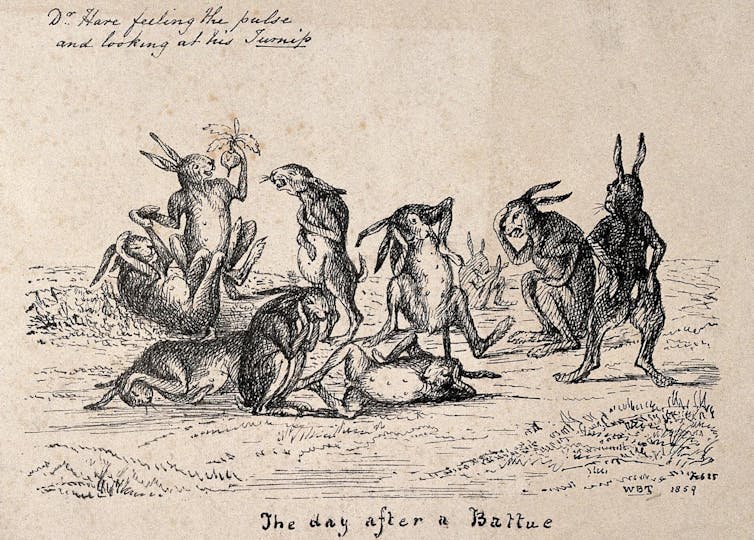

Lithograph showing hares enjoying turnips after being hunted, by WBT (1859). Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

Other now obscure but once favored root vegetables — skirrets and eryngoes — gradually fell out of British diets and parsnips and carrots were used less in sweet dishes partially thanks to the rapid increase in sugar production.

The global food chains that are at the heart of our current salad shortages mean that British consumers no longer need to eat (or individually produce) crops like turnips out of necessity.

It’s not surprising turnips couldn’t quite stand up to the huge changes in agriculture and food choice over the last three centuries. What their history does show, however, is that they have managed to survive despite it all, even if today’s consumers today aren’t really sure what to do with them.

Serin Quinn, PhD candidate, Department of History, University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.