“The Last Unicorn” at 40 is a poignant prophecy and reflection of today’s eco-grief

World leaders are wrapping up their discussions on the fate of the climate at the COP27 conference in Egypt. Outside the hall, protestors are rattling the doors, railing at resolutions too meager to keep warming temperatures under 1.5°C. Newspapers are reporting that wildlife populations have plummeted by 69% since 1970. And I am sitting in my pajamas, filled with impotent worry, watching an animated movie to soothe my anxieties about our fragile place in this world.

Extinction haunts the film from its earliest moments.

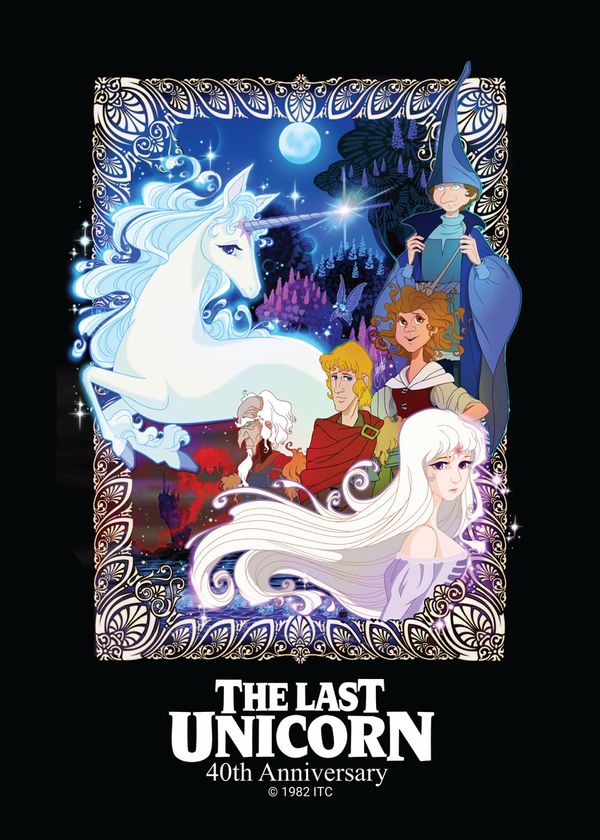

This month marks the 40th anniversary of “The Last Unicorn,” which was released in 1982. As a kid, I nearly wore through my VHS copy of the animated feature. It had everything: mythical beasts, witches, wizards, talking cats, buxom trees, drunk skeletons – and all of it underscored by the dulcet harmonies of ’70s light rock darlings, America.

It’s not strange to revisit the films you loved in your childhood. It’s not even that odd that I’ve seen the film close to a hundred times. Obsessive, maybe. What’s unusual about this movie is that, even though it’s 40 years old, it stares down the barrel of our immediate ecological concerns with more relevance than ever.

Directed and produced by animation duo Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass, the film is based on Peter S. Beagle’s 1968 unconventional fairy tale. While it was only a modest success at the box office, it has gained a dogged cult following in the decades since its release. In it, a unicorn discovers she is the last of her kind and seeks to discover the fate of her kin. She meets a ragtag group of compatriots who offer what aid they can as she navigates carnival prisons, fiery foes and the confusing fetters of the human form.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t relish the rewatches of my childhood favorites; if pressed, I could probably recite the dialogue of “Labyrinth” in its owl-flanked entirety. But as much as it galls me to admit it, these gems don’t always hold up to adult scrutiny. David Bowie’s vacuum-sealed pants are one thing, but a 300-year-old Goblin King chasing a 14-year-old Jennifer Connelly who is tripping under the influence of a roofie-packing peach? Feels pretty unsettling a couple decades down the road. Not to mention the riding crop.

But “The Last Unicorn” is different. Watching it as we endure year after year of record-setting temperatures, rising sea levels, and a growing list of extinctions, it feels nearly prophetic.

Extinction haunts the film from its earliest moments. When the titular unicorn first appears on her spindle legs, she tosses her delicate head and blue-white mane in haughty confusion. “Why would I be the last?” Mia Farrow’s breathy voice demands from her fellow woodland creatures.

The Last Unicorn (ITC)

The Last Unicorn (ITC)

“I’d read ‘Silent Spring’ when it came out, and the degradation of the environment was something discussed around my family’s dinner table,” said Peter S. Beagle, who adapted his own story for the screenplay. “But I have to admit that I didn’t hear the word ‘ecology’ for the next 10 years, and even then I didn’t know what it meant. I was just concerned about the chances of animal species going extinct. Trees and flowers were eternal – no matter what human beings did to or around them – weren’t they?”

Long before the publication of “The Last Unicorn,” the world had already mourned countless species, from the Stellar’s sea cow to the fabled passenger pigeon. In 1982, when the film was released, the International Union for Conservation of Nature finally signed the death certificate for the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger. A recorded sighting hadn’t taken place for nearly 50 years.

“It’s an important question to ask: who are we in the story?”

Since then, however, the rate of extinction has increased at such a clip that a whole new vocabulary has evolved to accommodate the loss. In the parlance of 2022, Farrow’s unicorn is an “endling”: the last of her kind. The concept has seeped so deeply into the bedrock of contemporary culture that there’s even a popular Nintendo Switch game called “Endling: Extinction is Forever.”

As significant to the film as the threat of extinction itself is the way in which the characters’ behaviors toward the unicorn mirror cultural responses to ecological crisis. One reaction is denial; most denizens of the unicorn’s world see only an ordinary white mare when they look at her. Those who recognize her for what she truly is yearn to help her – like Schmendrick (Alan Arkin), the amateur magician, and Molly Grue (Tammy Grimes), a maid several springs removed from her maidenhood – or seek to dominate and control her.

The Last Unicorn (ITC)

The Last Unicorn (ITC)

“It’s an important question to ask: who are we in the story?” posits Dolly Jørgensen, an environmental humanities scholar and professor at the University of Stavanger in Norway. Her book “Recovering Lost Species in the Modern Age: Histories of Longing and Belonging” delves into the cultural histories of animal extinctions. She, too, is a dyed in the wool fan of “The Last Unicorn” and references it in her lectures. “And I hate to tell you, but we’re generally not going to be Molly or Schmendrick. We’re certainly not the unicorn.”

Most characters the unicorn encounters reflect a problematic impulse to acquire rare creatures rather than fight for their survival. Mommy Fortuna, a wizened witch voiced by the late Angela Lansbury, cages the creature in a sideshow attraction to make a buck and secure her legacy in the memory of the deathless creatures she imprisons.

And then there’s King Haggard, the miserable monarch in his crumbling seaside castle whose only bid at happiness is hoarding all unicorns for himself. He’s become a trophy hunter of the world’s last remaining magic. Not to put too fine a point on it, but Haggard would fit in seamlessly with the 21st century’s space-race billionaires. And what better embodies the rising temperatures and ocean levels of climate chaos than Haggard’s fiery red bull that drives the enchanted creatures into the sea?

“Part of the mentality of ‘the last’ has been that, because they’re doomed anyway, you should collect them. You see that really explicitly in the Great Auk, where the last ones died because of collectors selling them to scientists,” Jørgensen explains. “In that sense, Haggard is not so foreign. We can’t assume, ‘Oh, we’re not like that. We don’t do that.’ Because, in fact, we do exactly that.”

The little girl in me who sat endlessly transfixed in front of a warped VHS recording is not pleased at this news. I don’t want to be a Haggard. The hits keep coming.

“In honesty, I don’t have a great deal of hope for this wondrous planet,” Beagle writes to me via email earlier this year. “Except on good days when I read a furious, demanding essay or article by some teenager somewhere. I feel more and more that the Earth knows exactly what’s wrong with it, and what needs to be done . . . and what could be done, if humans would just get out of the way.”

Let me tell you: nothing makes you need a stiff drink like the author of one of your formative childhood tales telling you he’s lost his faith in humanity.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

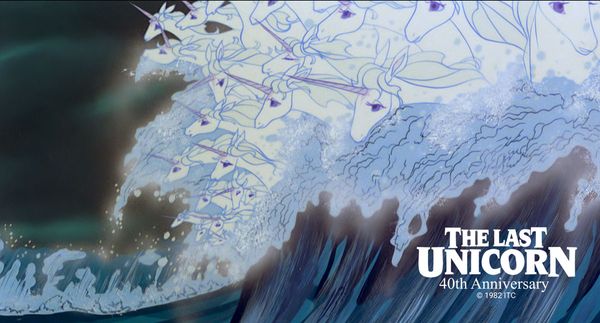

But Beagle himself penned a story over half a century ago in which a unicorn, nearly driven into the sea, must become briefly human to survive. This makes her unique among her kind: “Of all the unicorns,” Schmendrick explains, “she is the only one who knows what regret is – and love.” It’s this love that ultimately turns the tide of the story, giving the unicorn the strength to drive the bull into the ocean and free the rest of her species from the waves.

The Last Unicorn (ITC)

The Last Unicorn (ITC)

I wish I could say that the secret to solving the climate crisis could be found in a 1980s cartoon like a hidden Easter egg, but there are no easy answers here. And Jørgensen’s right: we’re not the unicorn. But by the end of the film, because of her brief transfiguration, we share something crucial with her.

When I’m consumed with regret over the environmental degradation I’ve witnessed and anxiety about where we might be headed, “The Last Unicorn” reminds me that it’s all part and parcel of maintaining an abiding love for our ailing world. And that if we can manage a happy ending – or at least avoid a tragic one – to our collective ecological narrative, it will be because of our giant, stupid, stubborn human hearts.

“The Last Unicorn” was honored for its 40th anniversary at the Academy Museum, for a show at New York Fashion Week and will be featured at a group art exhibition at the Corey Helford Gallery in Los Angeles from Dec. 17-Jan. 21.

Read more

about this topic