Won’t somebody think of Stephen King? Antitrust law and the publishing world’s mega-deal

Antitrust is having a moment. From both the left and the right, politicians clamor for new tools and enforcement to maintain a spirit of competition in the U.S. economy. While many focus on Big Tech, one of the Biden administration’s first big swings in a more aggressive antitrust enforcement regime took aim at a decidedly un-techy industry: book publishing. In a sealed ruling issued on Oct. 31, a federal judge sided with the government and blocked the merger of Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster. While the country’s attention was focused on the midterm elections, Judge Florence Pan unsealed her full opinion. In it, she sided with the federal government’s persuasive and creative legal thinking, which focused on harms to an unusual victim: highly paid authors. Faced with this setback, the merger officially collapsed this week when Simon & Schuster’s owner decided not to appeal.

It’s worth focusing on how the government achieved this victory. The fact that it felt compelled to make such an atypical argument shows how the current legal regime forces regulators to hide the ball in terms of whom they’re really advocating for in the courtroom. This trend isn’t limited to publishing; it also arises in one of the biggest of Big Tech suits — the case against Google.

If you’ve watched the animated Netflix series “Bojack Horseman,” you may remember the recurring gag of the omnipresent mega corporation AOL-Time Warner-Pepsico-Viacom-Halliburton-Skynet-Toyota-Trader Joe’s (which adds Philip Morris-Disney-Fox-AT&T to the front of its name by the end of the show’s run). While it’s unclear whether anyone in the Biden administration is a fan of this gone-too-soon comedy, there’s no doubt that the administration is taking a hostile approach to the type of corporate consolidation embodied in that joke. Biden has empowered a new wave of antitrust enforcers to give teeth to his view that “[c]apitalism without competition isn’t capitalism; it’s exploitation.” Accordingly, Merrick Garland’s Justice Department is fighting mergers and acquisitions across the board, in industries ranging from hearing aids to airlines to virtual reality.

Whether or not the Biden administration and the Justice Department are fans of “Bojack Horseman,” they seem to be taking on that show’s fictional mega-corporation and fighting mergers and acquisitions across the board.

That fight came to book publishing when a real life mega-corporation, Paramount Global — parent company of CBS, MTV, Nickelodeon, Showtime, BET, Comedy Central, Paramount+ and more — sold one of its many subsidiaries. In a $2.2 billion deal, Simon & Schuster was acquired by Penguin Random House (itself the result of a massive 2013 merger). The resulting company would have controlled nearly 50% of the market for “anticipated top-selling books.” Or so the government said.

That qualification was key. Analyzing how much of a market a potential company would control begins with establishing the bounds of which types of transactions count and which don’t. This exercise in “market definition” is a key part of almost all antitrust lawsuits.

It might seem as if defining the market here would be simple. After all, the publishing industry orbits around a “Big Five” made up of Simon & Schuster, Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hachette Book Group and Macmillan. But defining the relevant market proved to be an area of high contention throughout the three-week trial.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Before getting into the government’s creative market definition, we’ll need a crash course in publishing. Publishers promote themselves as one-stop shops for authors looking to get their books onto shelves. They edit authors’ manuscripts, produce the physical books, design ads and book covers, handle publicity and marketing and much more. At the start of this process, publishers typically compensate authors for their work in the form of a lump-sum advance. As part of signing with a publisher, authors and their agents agree to a (typically standard) royalty rate for each book sale (e.g., if a book sells for $20 and the author’s royalty rate is 10%, they earn $2 per sale).

Authors will not earn any income beyond the advance, however, until the amount generated in royalties exceeds the advance the author was paid up front by the publisher. Think of this as repaying a loan: Only once the publisher has recouped the advance (a phenomenon called “earning out”) will the author receive any further payment for that book. If the book earns out, then the author is compensated with royalty payments which reflect a percentage of future sales. But that’s a big if — most published books don’t earn out, which means that for most authors, the advance is the only compensation they’ll see out of their book.

Worried about the publishers’ bottom line in all this? Don’t be. They start making profits far before a book earns out.

The Department of Justice argued that properly evaluating the negative effects of the merger required defining the affected market as author advances over $250,000; it was that section of the market, constituting the type of books that may get custom merch rollouts on debut, that the government alleged Penguin Random House Simon & Schuster (or whatever the Frankensteined creation would call itself) would dominate. Conversely, the publishers insisted that the DOJ had invented this category exclusively to prove its point. Wisely, Judge Pan found that the publishers displayed “excessive concern” with where the government wanted to set its threshold (i.e., the government set it either too high or too low), as opposed to fighting against the concept of anticipated top-selling books itself.

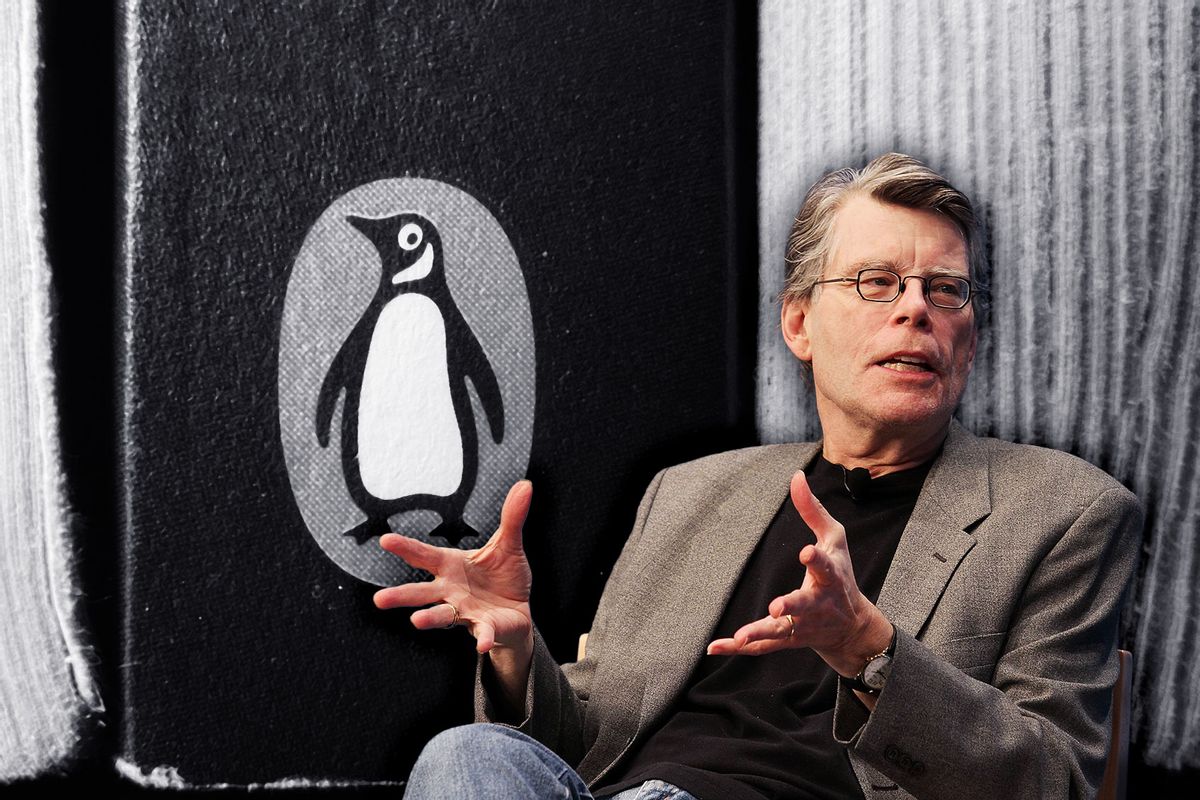

In focusing on highly paid authors, the DOJ bucked a typical antitrust trend. Many merger cases focus on resulting harms to consumers — typically higher prices. But experts believed that this merger would have been unlikely to raise the already high price of books. Focusing on author compensation allowed the DOJ to circumvent this problem. The government argued that authors would pocket smaller advances with only four publishers bidding on highly sought-after books instead of five. To prove its point, the DOJ had none other than Stephen King testify on its behalf (and, because he’s Stephen King, the publishers declined to cross-examine him, with one lawyer suggesting maybe they could instead grab coffee sometime).

Despite the courtroom drama and the clever lawyering, there’s something odd about the DOJ’s position — Stephen King, and other authors of his caliber, aren’t exactly helpless. The publishers seized on this weakness, arguing that these authors are “the elite of the elite” and the “least in need of protection by the antitrust laws.” In fact, at trial the publishers advanced their own narrative in which they themselves could be the victims of larger economic forces. The publishers touted their fears that blocking this merger might lead Paramount Global to sell Simon & Schuster to the financial bogeyman: private equity. Such an acquisition, they warned, could well result in Simon & Schuster being loaded with debt and gutted. Keeping her eyes on the ball, Judge Pan noted that such considerations were beyond the case immediately in front of her.

The government’s focus on highly paid authors is what sets this case apart from previous cases. As Judge Pan wrote in her opinion, much of the government’s case “sounds in ‘monopsony,’ a market condition where a buyer with too much market power can lower prices or otherwise harm sellers.” While less common, monopsony cases aren’t new to antitrust. Neither are cases focused on luxury markets. But what is new is a monopsony case focused on the highest-paid sellers. The closest analogue available for Judge Pan to cite was a case about two regional California movie theater chains, in which one chain amassed market power for “industry anticipated top-grossing films.” While the parallel between that market and a market of publisher-anticipated top-selling books is clear, the dynamic of whom would be harmed in the government’s publishing theory (i.e., rich authors, as opposed to the other movie chain) is novel.

Monopsony cases — where a buyer has too much market power — aren’t new to antitrust law. Neither are cases focused on luxury markets. But what is new is a monopsony case focused on the highest-paid sellers, such as Stephen King.

There’s a parallel between this strategy and the strategy pursued by a coalition of state attorneys general (AGs) in their antitrust suit against Google. In that case, the state AGs alleged that Google uses its monopoly power in the online advertising market to extract higher fees from both the sellers of ads and the sellers of advertising space. (Feel free to melt your brain attempting to understand the byzantine system of ad tech that Texas maps out in its complaint.) But the crux of the argument isn’t so hard to follow — because it faces virtually no competition, Google is able to wring more money out of both advertisers and the companies that receive money from those advertisers to display their ads.

Like highly-paid authors, large publications like ESPN.com and large advertisers like Ford are not the most sympathetic victims. Things are even worse when the victims are ad exchange companies with names unknown to the public. Aware of these potential limits to public and judicial empathy, both lawsuits connect the harms alleged here to consumer welfare. The DOJ alleges that a smaller publishing world would lead to fewer and less diverse titles available for the reading public to consume. Similarly, the state AGs allege that Google’s siphoning of advertising money leads to fewer profitable online outlets and less relevant ads to consumers.

But reading the legal materials, it’s hard not to feel that these arguments are afterthoughts; consumer welfare occupied two out of 160 pages of the DOJ’s brief and three out of 130 pages of the state AGs’ brief. And in truth, they are afterthoughts. What’s really going on here is a fight against consolidation. The government believes that consumers will benefit if it wins this fight, but not in a way that legal analysis is well-suited to evaluate. This tension leaked into every aspect of the publishing trial. On the witness stand, Stephen King testified that the average full-time writer in 2018 earned an income below the federal poverty line. From the point of view of a trial about authors getting paid advances over $250,000, this statement is irrelevant. Yet it reveals why the government and King are in the courtroom at all.

President Biden has said he wants to prevent “bad mergers that lead to mass layoffs, higher prices, [and] fewer options for workers and consumers alike.” Mergers are often followed by layoffs, which often disproportionately affect people of color. Experts worried that the merger of Simon & Schuster and Penguin Random House would lead to fewer writers, agents and editors of color working — in an industry that’s already 76% white. Their fears are rooted in the existing disparity in author advances for white authors and authors of color, and the notion that having fewer decisionmakers will result in fewer non-white authors being published.

Yet the dominance of economic analysis in the antitrust legal system means that the government’s best approach to fighting this merger was to focus on Stephen King’s bottom line. To the extent that this is what the law demands, the government can and must continue to advance these clever arguments. While Penguin Random House had the appetite to appeal, Paramount did not. The conglomerate’s decision to abandon the deal demonstrates how the government can turn these massive mergers into a massive headache when it has the legal tools to win. As reformers consider what types of changes we can make to live in a society further from AOL-Time Warner-Pepsico-Viacom-Halliburton-Skynet-Toyota-Trader Joe’s than closer to it, they must take their cues from Judge Pan. Even as her opinion swelled with data from economic models and simulations, it never lost sight of the bigger picture: Economic analysis is an analytical tool, not the ultimate referee of the antitrust world.

Read more

about law, books and money