Afghanistan’s Youngest Female Mayor Is Channeling Her Energy Into Activism

In 2018, Zarifa Ghafari became Afghanistan’s youngest female mayor. Below, read an exclusive excerpt from her book Zarifa: A Woman’s Battle in a Man’s World about her history-making mayoral appointment, fleeing Kabul after her father was assassinated in 2020, and returning earlier this year to a changed country.

When I arrived in Kabul in February of this year, my first emotion was gut-twisting fear, tinged with joy. Soon after our escape from Afghanistan, my family and I had been offered asylum in Germany, in the same small town my aunt lived in. We were settled in two clean and modern apartments, one for Bashir, my fiancé, and me, the other for my mother and siblings. I knew we were lucky to have been given a new home so quickly, but my mind and heart were still in Kabul. I followed each small development there on Facebook and Twitter, more engaged with the screen than with the world around me.

It was on Facebook that I learned about a woman in Ghazni province, south of Kabul, who was trying to sell her daughter. The girl, thirteen years old, was the youngest of four, and her mother was a widow. With the fall of the country to the Taliban, almost all the international aid organizations had pulled out their teams, and then crushing sanctions were slapped down, plunging the country into deeper poverty; however, since the Taliban’s return she had been unable to beg on the streets, much less go out to find work. She was asking for 2,000 euros for the girl. Instead of seeing all her children starve, the woman had decided it would be best to send one of them to another house, and bring in money to keep the rest of them alive. I asked a friend who was still in Afghanistan to track the woman down, and I began to collect donations for her. We were able to give 1,000 euros – enough to keep her daughter at home. Knowing that one girl had been saved gave me a brief buzz of happiness.

So I channeled my energy into activism, and started talking at events all over Europe, trying to keep the humanitarian and political crisis in Afghanistan on the international agenda, amplifying news of the Taliban’s crackdown on women’s rights activists who had remained in Kabul. With the money I earned from speaking and awards of cash prizes, I rebooted my humanitarian organization, Assistance and Promotion for Afghan Women (APAW). With the help of colleagues and my maternal uncle Haji Mama, I opened an educational and vocational training center and a maternity center in Kabul. I was now able to provide food packages to the very poorest women, mostly widows who had no income. Haji Mama sent regular updates, including photos that I would linger over, wondering what else I could do.

Most of all, I longed to go back.

At first, returning to Afghanistan was a vague wish. When a few airlines started resuming flights to Kabul my dreams sharpened into the beginnings of a plan with the assistance of the German foreign ministry.

I wanted assurance from the Taliban that I would not be arrested as soon as I arrived. I did not want to negotiate with them, nor meet with them in Kabul and be used by them as a photo opportunity to convince the world that they were treating women well. I knew that I was walking a thin line, and that many people would criticize my decision..

‘Afghanistan is your home and no one can take it away from you,’ said Zabihullah Mujahid, the Taliban’s spokesman, when I called him to tell him of my plan. ‘Whenever you want to come back, you have the right.’

The flight stopped over in Dubai, and as I waited there to board the Kam Air flight to Kabul, I studied the faces of my fellow passengers. In the air, I steeled myself for the reactions I might face on the ground. But when I first saw the mountains of Kabul through the window, the snow gleaming under the sun that I had yearned for during the dreary, dark months in Germany, I forgot all my fears. Whatever the politics, and whoever was in charge, Afghanistan would always be my home.

My first sight of the Taliban came as I put my bags through the scanner at the airport’s exit. When I picked them up on the other side, I came face to face with two men, sizing me up from behind a glass screen. I wondered whether the assurances I had been given were a lie; if I had walked into a trap, and was now going to be led directly into prison. The burlier of the two, dressed in camouflage and with a thick brown beard, locked his eyes onto me. After five long seconds, the Talib turned to his colleague and started chatting. I hadn’t realized, but I had been holding my breath.

The Afghan tricolors that had flown above the airport terminal had been replaced with the Taliban’s banner, a white flag inscribed with an Islamic incantation written in black Arabic script: There is no God but God. There were checkpoints everywhere; as spring approached, the new rulers were bracing for attacks. They had quashed the resistance quickly in August 2021, but the rival mujahideen factions were now regrouping, spurred on by opposition leaders outside the country who were calling for an armed uprising. Each night, the Taliban carried out security operations, going through Kabul district by district, searching every family home for weapons. The visa queue outside the Iranian embassy stretched hundreds of meters down the street, a line of people desperate to leave before the country descended into civil war yet again.

I found the real blowback of the past six months on the outskirts of the city, in Dasht-e Barchi, a poor district mostly inhabited by ethnic Hazara. Here, the snow had been cleared into pebbly heaps by the roadside and then blackened by the diesel fumes. Standing amid the grime were hundreds of people, offering up paltry wares: thin mattresses, rusted kettles, and bags of used clothes – mean household possessions they were trying to barter for a few hundred Afghani.

The sanctions and the end of aid operations were having an effect on the Afghan people that was far worse than the simple fact of Taliban rule. Poverty has always been searing in my country, but now an international freeze on Afghanistan’s assets meant that the new government could no longer afford to pay the wages of state workers. The little money left in the coffers was being creamed off by the Taliban and its supporters.

In Dasht-e Barchi, in a yard where chopped wood was stored under tarpaulin, a group of local women was waiting for me. I had asked the elders of the neighborhood to invite the poorest women, so that they might receive an aid handout of rice, flour, sugar, oil and tea that would keep a household sustained for a month. Before the distribution, I sat with them and asked about their lives.

As we talked, dozens of men gathered around the fringes, goggle-eyed. Now, one of them piped up.

‘Why is this aid only for women?’ he demanded. ‘Men need help, too. We have to work and support all the family. Why isn’t this aid coming to us? I have seven children!’

I have never backed down from debates like this. I thrive on them. I walked over to where the men were standing, and stood open-armed in front of all of them.

‘OK, so why did you have so many kids if you aren’t able to look after them?’ I asked the man. ‘And do you also allow your wife to work, to bring in some extra money?’

For a moment he was taken aback, not because he was ashamed of his choices, but because these were options he had never considered.

‘But women aren’t strong enough to work!’ he retorted.

I turned to the women, who were sitting patiently waiting for their packages. They had watched the whole scene with a bemused sense of despair.

‘What do you think, sisters? Are you strong enough to work?’ I asked them.

One of the oldest caught my eye, and raised her eyebrow. ‘That guy wouldn’t even be here if a woman hadn’t been strong enough to give birth to him,’ she sighed.

My maternal family never call me Zarifa – instead, they use my nickname, Krish, a shortened form of Krishma, which means affection. I had two personalities as a child: sweet one moment, and fiery the next, and over the decades my two names were the means by which my family came to accept my choices. The woman out there bossing men around? That’s Zarifa, with her armor of three tough syllables. The girl they know at home, soft and nurturing? That’s Krish.

My interview with 1TV, Afghanistan’s biggest private television channel, was recorded on my last evening in Kabul, to be broadcast as I was mid-air on the flight out. 1TV had been forced off air when the Taliban took control but it began broadcasting again on YouTube, from a new headquarters in Germany.

My interview would be my one chance to reveal what had been playing on my mind.

The 1TV interviewer asked me if I had any criticisms of the Taliban.

I did.

‘The Taliban,’ I began, ‘need to immediately release all female prisoners. Those who have fought for women’s rights, in the service of a better Afghanistan for everyone, should not be in a prison cell.’

I knew it was dangerous to say this. But to come back to Afghanistan and be so close to the women in jail, and not say anything about their nightmare? That was not just unthinkable to me – it was unacceptable. I would say my piece in the interview, weigh up the reaction from the safety of Germany, and decide later if another trip back to Afghanistan would be possible.

I spent my last night elated and proud at having had the courage to come back and look them in the eye.

My generation of Afghan women inherited nothing, and much of what we gained was taken from us. What we have left is now in the hands of a group we remember and fear. The rights that women still enjoy in Afghanistan – to go to school, to walk on the streets, to get a job – are bestowed on us by the Taliban, even as they lock up the women who have been fighting and striving for those things for years. We are allowed to have this much, but we must never threaten to ask for more.

The Taliban are a fact. No foreign army is coming to boot them out again, and the armed resistance is too weak to overthrow them. We know too that the Taliban are not inclined to treat women well, whatever mask they might momentarily wear. But if I can still find or create even the smallest space under the Taliban regime where women can learn, work, and give birth safely, if not freely, then I must continue to help.

Though some might say that what I am doing damages our cause, I ask, “Which war are Afghans really fighting?” To many Afghan activists outside the country, resistance means terror and guns. As women, we have suffered men’s slaughter for generations. My grandmother was a widow at twenty-seven; my mother was fatherless at three and a widow herself forty years later; I myself bear the weight of my father’s murder.

The Taliban say they are now more enlightened than they were in the 1990s. This is because they have been forced to be: for twenty years, my Afghan sisters and I have been devouring the opportunities presented to us to become doctors, supreme court judges, journalists – and mayors. Millions of us have learned to read and write, the first step to taking control over our lives. A young Kabul generation with no memory of the mujahideen’s civil war, we mingled in the coffee shops and accepted each other, Pashtun, Hazara and others alike. We helped to change our society in those two decades, and as a result the Taliban was compelled to reform.

I am prepared to speak with those I dislike and distrust, or whose ideas differ from mine, if it means that I carry on with my work. Better that than to shout from afar. I have the time and patience to continue this struggle, speaking with women one at a time, exchanging ideas and planting new seeds. Let official Afghan politics carry on without me. I am happy where I am, for now, and I am free.

I will keep reminding women that they have a voice, and can raise it. And that is why I fight on.

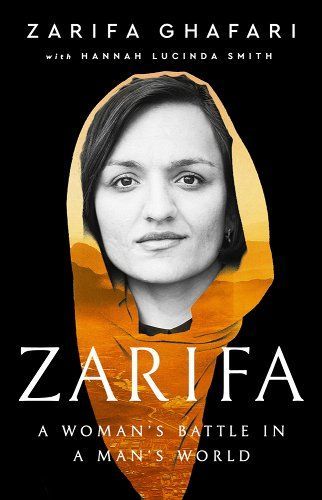

This article has been adapted from Zarifa: A Woman’s Battle in a Man’s World by Zarifa Ghafari with Hannah Lucinda Smith. Copyright © 2022. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group.