Whisky makers are turning their backs on peat

Mc’Nean

Mc’NeanNc’nean distillery sits above the sea, looking across to the coloured houses of Tobermory on the Isle of Mull.

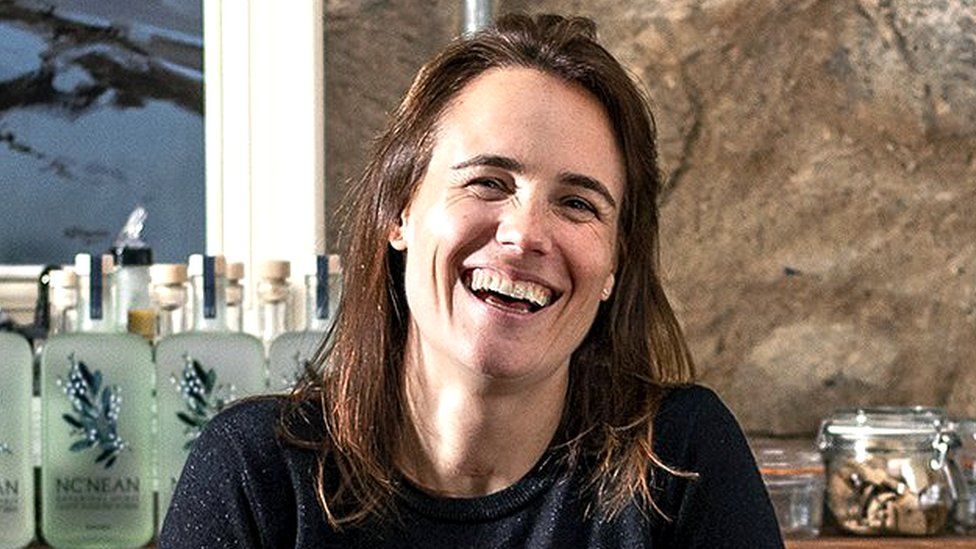

“We want to change the way the world thinks about Scottish whisky,” says founder Annabel Thomas, “to create delicious spirits that exist in harmony with nature – putting planet, people and profit on an equal footing.”

Ms Thomas, set up Nc’nean on her parents’ farm on the west coast of Scotland in 2017 and launched her first whisky in 2020. She never considered using peat. Traditionally, peat fires were used to dry malted barley.

“Extracting peat to burn is not sustainable. Peatlands are created over a very long time. They are a great carbon sink and house enormous biodiversity,” she says. “When cut and burned, it impacts both the biodiversity of the peat bog and releases carbon back into the atmosphere.”

However, Ms Thomas agrees using peat does make a big difference to the taste of whisky – but it’s not to everyone’s liking.

“You can taste it immediately,” she says. “It tastes smoky, some say like TCP!”

Ms Thomas prefers her whiskies un-peated, so it was not a difficult decision for her to cut it out of the process entirely.

“There is a misconception that all Scotch is peated but there are many unpeated whiskies from Scotland,” she says.

Whisky – made from fermented, often malted, grain such as rye, wheat, corn or barley – has been distilled in Scotland for hundreds of years.

In peated whiskies, malt grain is spread out over a perforated floor and underneath peat is burned, producing wafts of flavoursome smoke.

Whisky is made all over the world, and it’s not just in Scotland that peat is considered a vital component.

Belgrove, named after owner Peter Bignell’s family farm, is a small distillery on the north east coast of Tasmania.

The distillery, converted from an old cobbled stable in 2010, is a little noisier than most distilleries.

“Because of the chip oil burner,” says Mr Bignell. “I love being creative. It’s what drives my experimentation in the distillery.”

Belgrove uses biofuel made from waste chip shop cooking oil. They grow their own grain and, at the end of the process, the spent mash is fed to the sheep.

Using peat from the family farm, Mr Bignell employs several unusual peating techniques in a bid to get more out of this precious resource.

“Much of the smoking is done in a modified industrial clothes dryer,” he says. “I malt the grain in it, then smoke the green malt without moving it to another vessel.”

The wet grain tumbles through the smoke, he explains, and to increase the smoke level he often re-wets it.

“Re-wetting the grain part way through the process produces much more smoke,” he says.

Mr Bignell also crushes dry malted grain and dampens it. Smoke is then passed up through the damp grain bed.

“Crushing the grain first means it absorbs a lot more smoke from the same amount of peat.”

Another technique Mr Bignell uses is to smoke the inside of a barrel before filling it with spirit.

“A lot of smoke is lost during fermentation and distillation. By smoking a wet barrel, I found much more is retained than when you pass it through a still. Though, it results in a very different taste profile,” he comments.

Mr Bignell has also found a way to eliminate the use of peat completely – by burning sheep dung readily available on his farm.

Peatlands are naturally wet ecosystems.

In these water-saturated soils, there is little oxygen available for the microbes that breakdown organic materials, so decomposition happens very slowly. Remarkably well-preserved bodies have been recovered from peat bogs thousands of years after they were buried.

This lack of decomposition means that the carbon contained in all the plant and animal matter that makes up the peat, can’t escape back into the atmosphere.

Peatlands cover just 3% of land across the globe but store at least twice as much carbon as all the world’s forests.

They also play a vital role in filtering water. In Ireland and the UK, peatlands are responsible for around 85% of drinking water.

In addition, peatlands are home to an array of highly adapted species – many rare, threatened and in decline.

So, the environmental impact of damaged peatlands is multi-fold.

Angela Gallego-Sala is a professor of ecosystems and biogeochemical cycles at the University of Exeter. She studies peatlands across the world.

She says: “Globally, the whisky industry uses a tiny amount of peat – but the issue goes beyond carbon.”

To extract peat bricks, explains Prof Gallego-Sala, you have to drain the whole peatland.

“You affect not just the area of extraction but the whole peatland,” she says. “You break the ecosystem. You lose the biodiversity, the water cycling, the carbon cycling.”

Prof Gallego-Sala says we have a choice to make. “Maybe we love whisky so much that it is worth doing, but we need to make an informed decision.”

Fettercairn, a distillery in the Scottish Highlands, was founded 175 years ago. In recent years, they have been experimenting with flavours from wood charring, with whisky aged in barrels made from locally sourced oaks.

Nikki Cumming, Whyte and Mackay’s global brand manager, says: “Peat is a fundamental aspect of the whisky making industry. Each distillery has a history and for many distilleries that history involves peat.”

However, she sees whisky drinkers becoming increasingly open-minded to new flavours.

“At Fettercairn, peat has never been the focus, as we have a tropical style of flavour,” she says. “We’re building towards the future with local oak and grain so, hopefully, we’ll still be doing it hundreds of years from now.”

So, can whisky lovers learn to live without peat? Should they?

Prof Gallego-Sala adds: “These ecosystems are resilient. They can bounce back, but we don’t have much time to act. Protecting peatlands is one of the easier ways to make sure we reach net zero.”

Back in west Scotland, Ms Thomas sees an evolving whisky industry – and is optimistic.

“I hope the whisky industry will move quickly to more sustainable practices – replacing fossil fuels to power the distilleries, and addressing unsustainable agricultural practices.”