WTF happened to “Defund the police”? Author Alex Vitale on Ted Cruz and his “McCarthy moment”

In all likelihood, the U.S. Senate will confirm Ketanji Brown Jackson this week as an associate justice of the Supreme Court. She will be the first black woman and only the third black person to serve on our nation’s highest court in the history of that institution.

Unlike other recently nominated justices, Jackson is eminently qualified for the position and its great responsibilities. Instead of affording her the dignity and respect she has earned, Senate Republicans are expected to vote almost unanimously against her confirmation. This is wholly predictable, which in no way makes it less perfidious: Today’s Republican Party is the world’s largest white supremacist and sexist political organization. Jackson’s success is anathema to its apartheid plans for America.

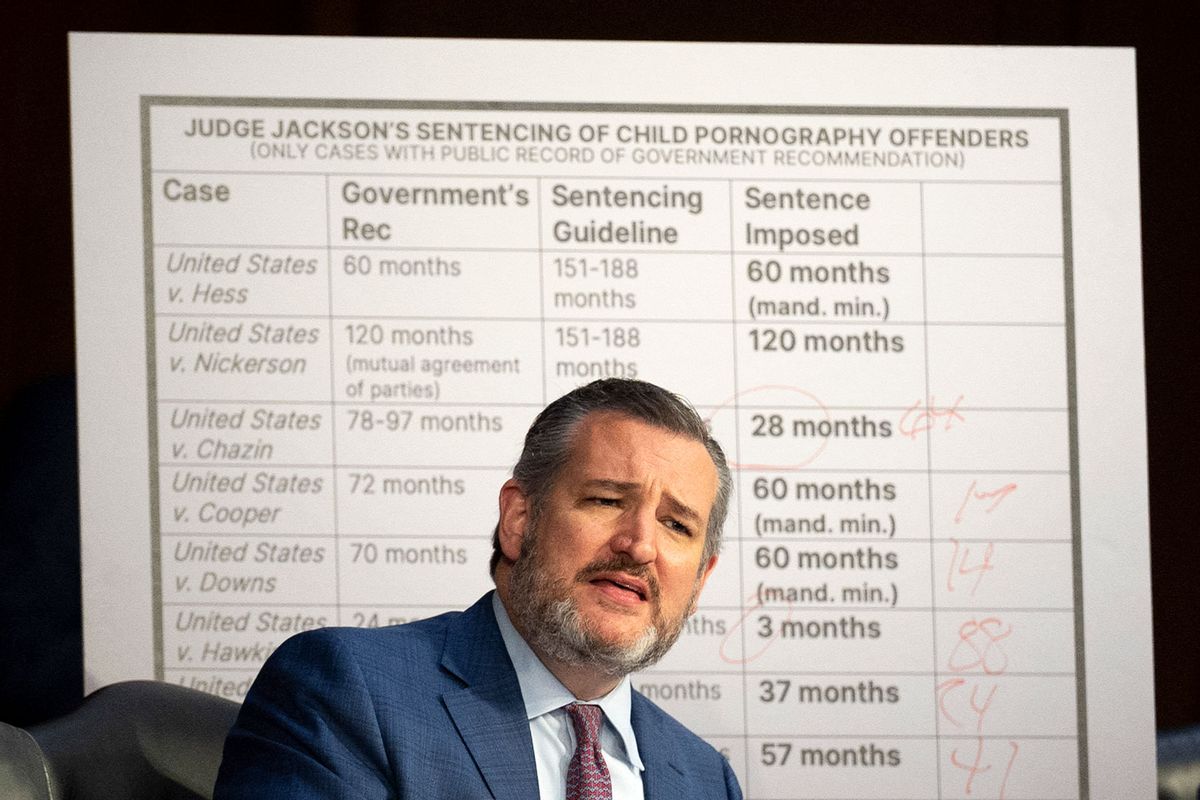

In their attacks on Jackson, Sen. Ted Cruz and other leading Republicans offered a disgraceful display of racism, sexism, anti-LGBTQ bigotry, conspiracy theories, anti-intellectualism and other antisocial attitudes. Their voters and supporters ate it up.

RELATED: Ted Cruz earns his “whiteness”: The Republican attack on Ketanji Brown Jackson

At New York magazine, Ed Kilgore described Cruz’s behavior as “the most disgraceful display of thuggish senatorial behavior I’ve personally seen in my many years of watching the upper chamber.” On MSNBC’s “The Sunday Show,” Tara Setmeyer described Republican rationalizations for their refusal to support Jackson as “asinine,” saying, “You’re just getting the musings of mediocre white men threatened by the excellence of this Black woman about to make history on the Supreme Court and they just cannot bring themselves to support her and support history.”

At one of the lowest crescendos in this disgraceful political theater, Cruz summoned up the specter of Joe McCarthy, holding up various books and denouncing them and their authors as un-American, “anti-white,” demonic promoters of “critical race theory,” products of the “family-hating” left and otherwise the enemy of good white patriotic Americans everywhere. One book Cruz chose to brandish, like an inquisitor presiding over a witch trial, was “The End of Policing” by sociologist Alex Vitale, a professor at Brooklyn College, where he is also the coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project.

In an essay at The Nation, Vitale responded to Cruz’s dishonest use of his book, joking that he “was honored to be included” in the senator’s list of so-called “critical race theory” texts, but that his book is not part of that “specific school of legal scholarship,” and the “intentional confusion is actually a dangerous attack on the movements to advance racial justice in America”:

Cruz hopes both to suppress ideas critical of core American institutions and to gin up a white nationalist backlash — one that can not only be used to rally the GOP base at the polls but also be deployed against calls to end mass incarceration, reduce our reliance on policing, and invest in the schools, communities, and families that have suffered generations of discrimination, abuse, and defunding.

Cruz and his fellow travelers are committed to the myth of color-blindness, in which race is reduced to a discredited ideology of the past. According to this view, we don’t have active racism in the United States, and anyone who complains of it is mobilizing a form of “racial essentialism” that not only discriminates against white Americans but also relegitimizes race as a real thing.

That is not, Vitale added, how racism works in the real world.

I recently spoke with him about that moment and what it reveals about white backlash politics and white supremacy, the “defund the police” movement, and America’s broken system of policing and law enforcement. Vitale explains what “defund the police” really means and why Democrats remain beholden to “law and order” politics despite the societal harm and human destruction it causes.

Vitale further discusses how “copaganda” distorts the average American’s understanding of policing, crime, and public safety in America. He warns that America’s police and law enforcement have long been agents of right-wing authoritarianism and other forms of reactionary and regressive politics. Vitale also reflects on what the police murder of George Floyd and the months of protests it caused have meant for the larger movement to fix American policing and address the larger system of mass incarceration that Michelle Alexander has famously described as “the new Jim Crow.”

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

How did it feel to see “The End of Policing” being held up by Ted Cruz during Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation hearings? It was like your own 21st-century McCarthy moment?

I saw it as a badge of honor. My book was included in a list of really amazing books that have been banned or otherwise used to by the right to wage racist, closed-minded attacks on reality and the truth.

Cruz was using your book as a prop in a larger performance of political theater. What was he trying to accomplish?

My book “The End of Policing” is not part of the tradition of legal scholarship referred to as critical race theory. In a way, Cruz was tipping his hand to that fact by saying that what he and they are really opposed to is anyone talking about racism in a serious way in America at all. What they are really trying to do with these attacks is to shut down any substantive conversation about the real history and true nature of American racism.

Do you believe that Ted Cruz’s overall performance and use of your book was effective for his audience?

Cruz was playing to his base. I don’t think his performance got more of those people to read my book or to think critically about these ideas.

What is the actual thesis of “The End of Policing”? And how do we reconcile the actual evidence with Cruz’s fear-mongering and this moment of white backlash more generally?

Ted Cruz was certainly making the link between American society’s uncritical reliance on policing and the toxic politics of racism in this society. We cannot really understand the institution of policing here in the United States independent of conversations about the legacy and ongoing practices of racism in this country.

What does “defund the police” actually mean? What does it look like in practice? And how do you explain the resistance to the idea, even among people who live in poor and underserved Black and brown communities?

People in underserved communities have been told the only resource available to deal with neighborhood problems is the police. When the media says, “Defund the police,” all it means to those people is that their only resource will be taken away.

For too long, people who live in underserved communities have been told that the only resource that’s available to them to deal with neighborhood problems are the police. When the mainstream news media says, “Defund the police,” all it means to people in those communities is that we’re going to take your police away. Of course, that does not sound very appealing. When we’re out there doing actual face-to-face organizing at the community level about how to make these communities safer, the “defund the police” efforts tend to be much more successful. We have to get beyond trying to win this battle in an abstract national public conversation and instead we need to double down on face-to-face neighborhood organizing.

I don’t have any particular allegiance to that three-word phrase, “defund the police.” The data shows us that when people are asked a clear question about whether they think much of what police now do could be accomplished better in other ways, there is a lot of support for that idea. Black and brown communities know they need better community centers and better health care services and better jobs for their young people, but they have always been told they can’t have those things.

Beyond your book, what other resources would you suggest for people who want to learn more about the “defund the police” movement?

They should read Derecka Purnell’s book “Becoming Abolitionists.” They should read “Abolition. Feminism. Now.” People should also take a look at the Defund the Police website to learn about the various campaigns underway all across the country.

RELATED: Who will keep us safe in a world without police? We will

During Biden’s State of the Union speech, he explicitly attacked the idea of defunding the police and received great applause from both Democrats and Republicans. Why are the Democrats unable to quit “law and order” politics?

Biden’s political career has been very consistent. There’s nothing new with those comments. Biden has consistently relied on policing to paper over the consequences of terrible economic and social policies. Biden has been part of a generation of politicians in both parties that have systematically defunded poor communities and communities of color in terms of their schools, mental health services, jobs and other areas. In response, the police are used as a way to cover over the problems of mass homelessness, underemployment, untreated mental health and substance abuse problems. Asking Biden and politicians in both parties to give up the politics of austerity is a radical demand, and predictably they are resisting it.

Why does the lie persist that America’s police are somehow underfunded?

It is reflection of the “war on cops” mentality that has been perpetuated by the active misinformation campaigns coming from right-wing think tanks such as the Manhattan Institute that are funded by billionaires and hedge fund managers. Their goal is to turn the systemic problems of this society into problems of individual moral failure that in turn are to be fixed by policing. They will make up whatever narrative fits their larger goal of absolving themselves of any responsibility for the country’s problems.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

There is a predictable narrative that plays out whenever a police officer is held responsible for murdering or otherwise committing crimes against the public. Some politician or other public voice announces that “the system works” and that this time the legal system and the courts “got it right.” If a jury is involved, then on cue some talking head will praise the integrity of the average American. It is all so tedious. The vast majority of police and other law enforcement are never held responsible for their crimes. How do you explain that narrative?

When police injure people on the job, the political and legal systems view that as an unavoidable cost of doing business. Nothing changes when those officers are incarcerated. It makes no difference.

When police injure or kill people on the job, the political and legal systems view that as an unavoidable cost of doing business. They protect police officers who engage in such violence because political leaders have told the police to wage a war on crime and a war on drugs and a war on terror and a war on gangs and a war on the poor, and that means there will be violence and death. If politicians and other policymakers want the police to wage these wars, they have to then protect the police from any consequences of that brutality. The only exception are those cases that are so egregious and so visible that they threaten the fundamental legitimacy of the police as an institution. That explains what happened in the George Floyd case, where the police department turned against the officers involved to save the department. Nothing changes when these officers are incarcerated. It makes no difference to how policing is done in these communities.

What has happened in the almost two years since the George Floyd protests? Much has been written in the media about the lack of change in terms of policing and mass incarceration since those nationwide protests. Many people had high expectations and wanted to see immediate positive change. Largely, that has not taken place.

The movement was alive and well before the George Floyd protests. It was taking place in hundreds of communities at the grassroots level in the form of community meetings and people showing up at budget hearings for example. For the most part, that work is continuing. The movement is winning substantive victories. Dozens of cities have eliminated their school police. Dozens of cities are putting in place non-police crisis response teams. Dozens of cities are spending more money on community-based anti-violence initiatives. On the local level, despite resistance from mayors and others, the movement is still winning victories.

What does the police murder of George Floyd represent or exemplify, in terms of American policing and the culture of law enforcement in this country?

After the police killed Mike Brown, Amir Rice, Eric Garner and so many others in that period, about six or seven years ago, we were told not to worry. Policing was going to get fixed. We’re going to reform the police, right? All these experts trotted out all these police reforms, but the officers involved in the killing of George Floyd, including the four who stood there and watched it happen, all had this new training. They’d had implicit bias training and de-escalation training and mindfulness training and they were subjected to new oversights. Those police were wearing body cameras. They were operating under a new, more restrictive “use of force” policy. They were operating under a policy that required that officers intervene if they see misconduct by a fellow officer. None of it made any difference.

George Floyd’s life did not matter to those police officers. We have to give up this idea that we’re going to create “Officer Friendly” with a few training programs. Instead we’ve got to get rid of the war on drugs, the war on gangs, the war on terror, the war on immigrants and the war on our own children in their own schools, and start solving our social problems in ways that try to repair harms and lift people up instead of endlessly criminalizing and brutalizing them.

What do America’s law enforcement and other policing practices reveal about this society?

We have turned so much over to the police that they are now a massive presence in our society. As a function of that, policing as an institution serves as a kind of lens for understanding a whole set of social dynamics, whether it’s the rise of right-wing extremism, the criminalization of poverty or the failures of our public health systems. Policing is a thread that runs through all those important societal dynamics.

How are America’s police linked to the rise of Trumpism and other neofascist and authoritarian forces?

In broad terms, there is a great deal of sympathy for very conservative politics among law enforcement. We also know that is part of a long history of such behavior. The police have historically been heavily represented in extremist, nationalist and white supremacist organizations, including the John Birch Society, the KKK and various other right-wing movements going back at least 100 years. We also know that there are a number of police officers who are active members of current right-wing extremist organizations. We know the FBI has uncovered a number of instances of this. It should be of concern to us that policing in America is so heavily associated with these extremist movements.

Who wants to become a police officer? What do we know about them as a group?

It is somewhat difficult to draw broad conclusions, for a few reasons. One is the lack of data in general. Police departments remain very opaque and resistant to sharing data with the public. For example, we still don’t know how many people the police kill every year in the United States. Policing is also incredibly decentralized. There are somewhere between 18,000 and 20,000 police departments in the United States. We don’t even know how many, no one can tell you definitively how many police departments there are in the United States. And there are obvious differences between a rural sheriff’s department and a big-city police department in terms of the profile of recruits, what the career trajectory looks like, and the nature of the training they undertake.

My experience is focused more on the big city departments, which have become much more diverse. The membership of these police departments is mostly made up of young people looking for secure, well-paid employment that requires very low academic credentials. In many cases, only two years of military service or two years of community college are required to become a police officer, and in some cases even less than that. A police officer can quickly make a six-figure salary and retire after 25 years. Becoming a police officer is a kind of “poverty draft” that is quite similar to what is used to entice young people from low-income backgrounds to join the military. They are offered large salaries with low thresholds for entry and early retirement.

Being a police officer in America is one of the few jobs where someone with a high school education can get a gun and have the permission to basically kill without accountability and also make good money.

The vast majority of police officers never fire their weapons. Shooting and killing someone is even more rare. But of course the consequences for those killings are almost nonexistent. We’ve created a situation here in America where an ever-growing list of social problems are turned into problems to be managed by policing. We’ve redefined problems of poverty, inadequate health care, failed schools and struggling families into problems of crime and disorder to be managed by “violence workers,” because that’s really what distinguishes police from other government workers, that capacity and authorization to use violence.

America is in the midst of a perverse situation where our cities are now filled with violence workers micromanaging the affairs of the poorest and most vulnerable people in our society. Those are the origins of a great deal of the racialized violence and killings that we see with American policing today.

What are some of the most prominent myths about American policing?

We have a lot more information about the deaths of police officers than the other way around. We know that policing is not without danger, but it is on par with other kinds of blue-collar professions such as construction, farming and industrial work. In fact, those professions often have higher levels of on-the-job deaths than policing does. Many of the deaths of police involve accidents, mostly from traffic and high-speed police chases.

Talk about the American cultural myth of “Officer Friendly” and the inherently good and noble heroic cop?

One of the most important myths about policing is that police exist primarily to manage problems of violence and that police are doing what you see on television, which is chasing bank robbers and finding hidden serial killers. In reality, that has very little to do with what police actually do on a day-to-day basis. Patrol officers aren’t even generally involved in law enforcement. They’re involved in managing problems of disorder. Most police officers make about one felony arrest a year — that’s it. If you watch “Law & Order” and “Blue Bloods” and other such police-themed TV shows, one would think that every week the average police officer is making four or five felony arrests. Such depictions create the idea that the world is much more dangerous than it actually is.

The other distortion of reality is that police are much more effective than they really are. In total, we as a society overestimate the effectiveness of policing, we fail to calculate the real costs of policing and we’re largely ignorant of the alternatives to policing.

How does the myth-making propaganda machine known as “copaganda” work in practice?

It takes different forms. The most extreme examples are the shows that have historically been essentially co-produced by police departments. This goes back to shows like “Dragnet” in the 1950s and “Adam 12” in the 1960s and ’70s. More recent examples are shows like “Cops” and “Live PD” that work directly with local police departments who also have veto authority over the content. These shows have been essential to producing certain kinds of narratives about the heroic nature of policing and the unquestionable need for policing in all its many forms.

The other distortion is a function of how the entertainment industry works more broadly. There the problem is more an issue of the need to produce weekly shows that are filled with action, adventure and mystery. That formula only works if there are lots of horrible, evil people out there for police to find every week. This distorts reality and creates a narrative where, “Oh my God, the world is so dangerous, and the police are out there catching all the bad guys and also bending and breaking the rules to do it.” If they have to rough some people up, if they have to intimidate people in interrogations, if they violate people’s Fourth Amendment rights, well, that’s just a cost of producing safety.

Local news has been particularly terrible in terms of crime coverage and exaggerating what is really happening in the community. Local media treats the police as unassailable and the font of all truth. By the time the real facts come out, the media has moved on to the next set of horrors.

There is of course the news industry and the whole problem of “If it bleeds, it leads.” Local news has been particularly terrible in terms of crime coverage and exaggerating what is really happening in the community. National crime stories came to dominate local news, because they want some horrific crime to cover and there just weren’t any in their local coverage. Finally, the local news media treats the police as completely unassailable and as the font of all truth. By the time the real facts have come out, the media have moved on to the next set of horrors to cover and the public rarely gets the full story.

How do we deconstruct the political work being done by language such as “Blue lives matter” and the “Thin blue line”?

“Blue lives matter” is a deeply conservative ideology that is being used by political forces, and not just the police, to advance extremist authoritarian politics. As we saw on Jan. 6, 2021, the actual lives of police officers are irrelevant. These authoritarians and their followers will happily throw police officers under the bus if it serves the larger authoritarian objectives.

RELATED: Conservatives go after Capitol police officers who testified before Jan. 6 commission

At root, the “thin blue line” narrative is a Manichean worldview that divides the world up into the good people and bad people and imagines that police are the force that separates those two. That narrative ultimately decides what type of person goes on which side of the line and then crosses out the people deemed to be “dangerous.” That is an incredibly superficial understanding of the real dynamics of human nature. People are not all good or all bad. Good people do bad things. When we apply the “thin blue line” logic, it deems that entire segments of the population are essentially disposable, and that’s the root of the ideology behind mass incarceration. It’s the root of the ideology about putting police in our schools. It’s the root of an ideology that says that homeless people and people with mental health and substance abuse problems need aggressive policing, not medical care, housing and income support.

Ultimately, it is the logic of saying that the world’s problems are not the result of market failures or government inaction. Instead, at their core these problems are caused by individual and group moral failures that will only respond to intensive, invasive and violent interventions. That is the battle we as a society are having right now: Are we going to start treating people as human beings who can be worked with, helped and lifted up, or as less than human to be disposed of, warehoused and executed?

What do we actually know about American police and the violence and other harm they commit against Black and brown people in this country?

Police kill Black and brown people disproportionately more than white and Asian people. In fact, the population that’s most disproportionately impacted by police violence are Native American communities. Police defenders will say something like, “Well, if we look at the race of violent criminals, then the levels of police violence appear more consistent.” The problem is who decides what a violent crime is and how policing in America deems certain people to more likely be “violent criminals” than others. For example, when we extensively surveil and police Black and brown communities, their involvement in violence is going to be highlighted and brought to police attention in a different way than violence that may happen in a white suburb.

I have an acquaintance who’s been both a prosecutor and a criminal defense attorney. He often jokes that if the police treated white neighborhoods and suburbia the same way they do poor Black and brown neighborhoods, there would be a lot more white folks in jail.

No one is running “buy and bust” operations on Wall Street to find people with cocaine and heroin and other hard drugs in their system. We also know that the use of hard drugs is widespread among that group. We know that drug use is widespread in America, but the drug war is something that is only played out in poor communities.