Ashley Biden’s diary, Project Veritas, the Trump campaign and the New York Times

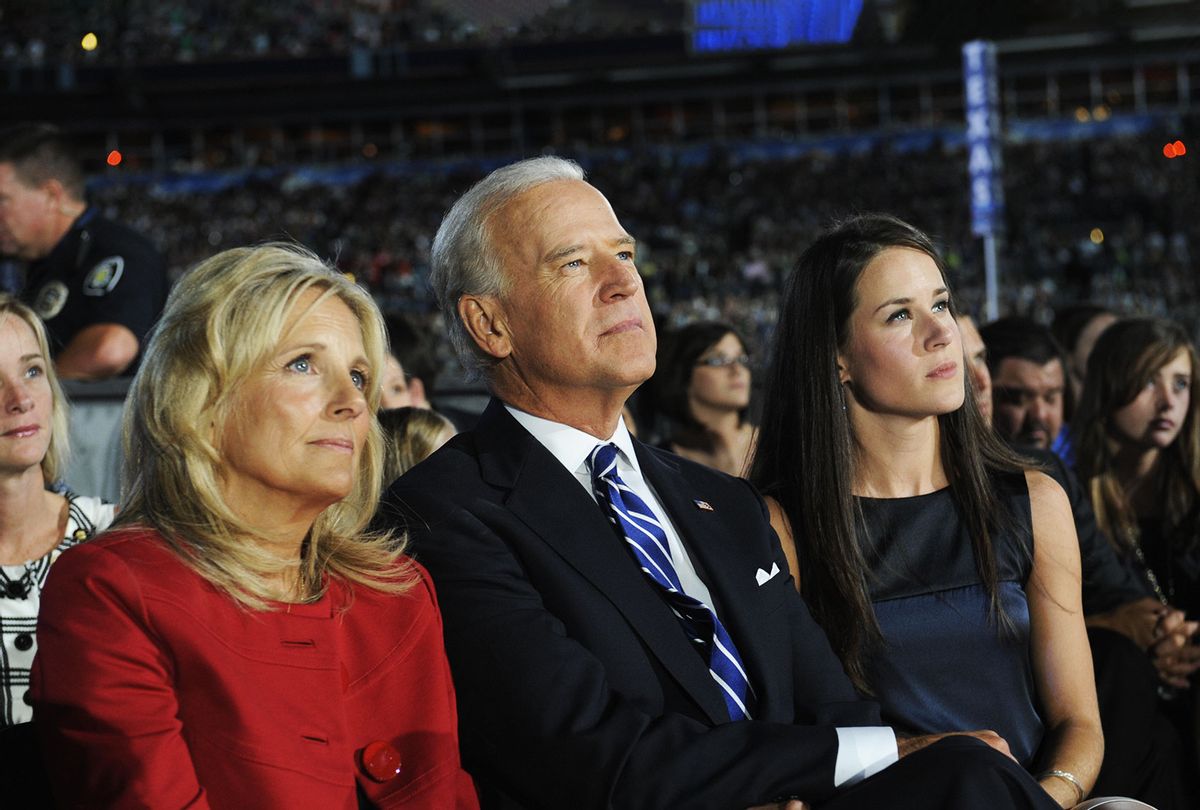

A Florida woman tried to shop around the diary of Ashley Biden, President Biden’s daughter, during a 2020 Trump campaign fundraiser attended by Donald Trump Jr. before it was obtained by the conservative group Project Veritas, according to The New York Times.

The FBI in November raided the homes of several current and former Project Veritas members while investigating the theft of Ashley Biden’s diary, the contents of which were published on a different right-wing website shortly before of the 2020 election. Project Veritas denied that it had illegally obtained the diary and said it had “no involvement” with the two individuals that acquired it.

Project Veritas founder James O’Keefe, a Trump ally, claimed that he learned of the diary from “tipsters” and said the group made an “ethical” decision not to publish it because they could not authenticate it. The group, which regularly conducts undercover stings intended to embarrass liberal groups and journalists, has insisted in court filings that it is protected under the First Amendment as a news publisher. The Times report suggests the group may have tried to “trick” Ashley Biden while trying to authenticate the diary. In response to Project Veritas’ argument, prosecutors accused the group of making statements that are “false or misleading and are directly contradicted by the evidence.”

The diary was found at a Florida home where Ashley Biden, who was recovering from addiction, had previously stayed, according to the Times report. (When she moved away, Ashley Biden reportedly agreed to store some personal belongings with the owner.) The diary was later shown around a Trump fundraiser in Florida at the home of a donor who was later nominated by then-President Donald Trump to a federal position. Shortly after that, Project Veritas obtained the diary and asked the couple who had originally acquired it to retrieve more items from the home where Ashley Biden had stayed to verify that it was hers, according to the report. A caller from Project Veritas’ headquarters in New York later tried to “trick” Ashley Biden into confirming its authenticity, using a fake identity in a phone call offering to return it, according to the Times. That apparent effort could complicate the group’s claims that its activities were protected under the First Amendment.

RELATED: FBI raids homes of Project Veritas associates as part of probe into theft of Ashley Biden’s diary

In July 2020, a woman named Aimee Harris moved into the home of an ex-boyfriend in Delray Beach, Florida, amid a custody dispute. She learned Ashley Biden, a friend of the ex-boyfriend, had stayed there during the pandemic, according to the report. Ashley Biden had left several bags of her belongings, including the diary, at the house after moving back to the Philadelphia area, saying she planned to retrieve them later. In August, Harris, who supported Trump, reached out to another friend, Robert Kurlander, a Biden critic who served 40 months in prison for fraud in the 1990s, and hatched a plan to sell the diary to help pay for lawyers in her custody battle, according to the Times.

Kurlander then contacted Trump donor Elizabeth Fago, who hosted the fundraiser that was attended by Donald Trump Jr. and was later nominated by President Trump to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Harris and Kurlander attended the fundraiser at Fago’s home three days later where they showed it to others and sought to find out whether Trump’s campaign “might be interested in it,” according to the Times.

It’s unclear whether Donald Trump Jr. or anyone affiliated with Trump’s campaign saw the diary. Mark Paoletta, a former lawyer for ex-Vice President Mike Pence who was hired by Project Veritas to lobby congressional Republicans to push back against an FBI probe into the group, initially told the lawmakers that Trump Jr. had “showed no interest” and said it should be reported to the FBI, according to the report. Paoletta called the lawmakers back later, however, to say he was “unsure whether the account about Donald Trump Jr.’s reaction was accurate.”

Project Veritas then sought to acquire the diary after learning about it in September, according to the Times. Harris and Kurlander flew to New York to meet with members of the group and began negotiating a $40,000 deal to sell the diary. The two sides failed to reach an agreement and Harris and Kurlander went back to Florida. Project Veritas also sent Spencer Meads, one of O’Keefe’s top lieutenants, to do more digging in the state.

Project Veritas later said in court filings that it had obtained items belonging to Ashley Biden that its “sources” described as “abandoned.”

“The sources arranged to meet the Project Veritas journalist in Florida soon thereafter to give the journalist additional abandoned items,” the group said in a court filing.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

That somewhat conflicts with Harris and Kurlander’s statements to others told others that someone from Project Veritas directly asked them to retrieve more items belonging to Biden, according to the Times.

Project Veritas lawyers had repeatedly instructed the group not to encourage sources to steal evidence. In a 2017 memo obtained by the Times, one of the group’s lawyers noted that Project Veritas “enjoys substantial legal protections to report and disclose material that may have been illegally obtained provided it played no part in obtaining it.”

Federal prosecutors say the group played a key role in obtaining the evidence. “Put simply, even members of the news media ‘may not with impunity break and enter an office or dwelling to gather news,'” prosecutors said in a court filing, disputing the group’s “repeated claim that they had ‘no involvement’ in how the victim’s property was ‘acquired.'”

In October 2020, a caller who did not identify himself as a member of Project Veritas and used a fake name offered to return the diary to Ashley Biden in an effort to authenticate it. Members who heard recordings of the call said they believed that Ashley Biden had said “more than enough to confirm that it was hers,” according to the report.

On Oct. 12, O’Keefe sent an email to his team saying he had decided not to publish a story about the diary despite having “no doubt the document is real,” Project Veritas told a federal judge. O’Keefe said in the email that the story would be “characterized as a cheap shot.”

But four days after that email, a top lawyer for the group told Joe Biden’s campaign that it had the diary and wanted to interview the candidate about it, according to the Times. Less than a week later, Project Veritas wired $40,000 to Kurlander and Harris and signaled that they planned to publish the story after all.

That never happened. Instead, an obscure right-wing site called National File published handwritten pages from the diary that it said it had obtained from a Project Veritas whistleblower. O’Keefe was “furious” that one of his own operatives may have leaked it out of frustration with their refusal to publish it, according to the Times.

A lawyer for Project Veritas flew to Florida and turned over the diary and other items belonging to Ashley Biden to the Delray Beach Police Department, saying that the items were “possibly stolen.” The department informed the FBI, which sent an agent to retrieve the items.

The FBI interviewed Kurlander and Harris nearly a year later and raided the homes of O’Keefe, Meads and another Project Veritas operative named Eric Cochran two weeks later.

O’Keefe did not comment on the Times report but criticized the paper for publishing it. “Imagine writing so thoroughly divergent from reality and so mendacious with innuendo that there is literally no utterance that won’t make it worse,” he said in an email.

O’Keefe has repeatedly denied that Project Veritas has ever done anything illegal. “We never break the law,” he said in a YouTube video last year after coming under FBI scrutiny. “In fact, one of our ethical rules is to act as if there are 12 jurors on our shoulders all the time.”

Project Veritas, which has been backed by former Blackwater founder Erik Prince and was trained by a former MI6 officer, has often come under criticism for its “stings,” which typically involve getting journalists or liberal political figures to say something embarrassing on hidden video, often under false pretenses. Some efforts have been more daring. In 2018, the group launched an operation to set up Tinder dates with employees at the Justice Department and other federal agencies and then record them secretly, in hopes of finding evidence of an anti-Trump “deep state.” The group’s lawyer in a memo warned that the effort could risk violating the Espionage Act, according to the Times.

Journalists say the undercover nature of the group’s work may not be illegal but is highly problematic.

“It opens you up to the charge that you’ve been intentionally deceptive and you lose your moral standing,” Bill Grueskin, a professor at Columbia Journalism School and former editor at Bloomberg and Wall Street Journal, told the Times. “Every newsroom I’ve ever worked in has basically said undercover journalism was unacceptable. I’ve never had a reporter tell me he wanted to pose as somebody they were not.”

New York Times reporter Jonathan Weisman agreed that the group “uses deceptions that no reputable news organization would use.”

Project Veritas, which has dealt with a range of legal issues, last year asked a judge to block the New York Times from publishing an article that included excerpts of memos prepared by one of the group’s lawyers. A judge granted the motion but a New York State appeals court temporarily lifted the prior restraint order last month to allow the outlet to publish certain documents.

Ted Boutrous, one of the most prominent First Amendment attorneys in the country, called out Project Veritas for seeking to block news stories about itself while demanding broad First Amendment protections for “illegal activity” which “the First Amendment would not protect.”

“Project Veritas cannot hide behind the First Amendment when it wants to speak out,” Boutrous tweeted, “and then trash the First Amendment when it wants to shield itself from scrutiny simply by self-styling itself as a news organization.”

Read more: