In Trump’s America, we can find courage and refuge in poetry

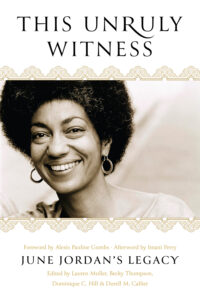

If we are to understand the complexities of the human experience, it is the poet who is best able to articulate, to bear witness — not only as archivists, but as social and creative provocateurs for the sake of society or a communal experience. In reading “This Unruly Witness: June Jordan’s Legacy,” an anthology of writing about poet, essayist, professor and activist June Jordan’s work edited by Lauren Muller, Becky Thompson, Dominique C. Hill and Durrell M. Callier that features literary luminaries like Angela Davis, Naomi Shihab Nye and E. Ethelbert Miller, I was reminded the poet is undefeated, as she sees everything that we as a society do not or refuse to acknowledge.

“This Unruly Witness: June Jordan’s Legacy” will be published on Nov. 11, 2025.

When June Jordan died in 2002, I was being reborn into the world of literature after a five-year prison stint inside the carceral state. I was reordering my life’s purpose. While studying in an MFA graduate program in Chicago, I read “Soldier: A Poet’s Childhood,” which in turn led me to “Poem About My Rights,” and its searing indictment on the violation of women and their bodies, not only domestically, but also abroad. I realized Jordan was a poet I could believe in, a poet truly of and for the people. “This Unruly Witness” is the book I wish I could have read after encountering “Poem About My Rights” to better understand the breadth and width of this amazingly unafraid poet, and to gain a better definition of what it means to embrace humanity.

With a foreword by Alexis Pauline Gumbs and an afterword by Imani Perry, the editors of this carefully curated collection weave a mosaic of narratives from those who studied with and were mentored by Jordan. Divided into three sections hinged together by a through-line of humanism, Elizabeth Alexander reminds the reader that Jordan “was a prolific poet whose lyrical voice linked political struggle with an ethic of love.”

Jordan understood the danger of a common identity versus free will, and how the barriers of a state-sanctioned identity are both disastrous and dangerous to humanity’s evolution.

Jordan understood the danger of a common identity versus free will, and how the barriers of a state-sanctioned identity are both disastrous and dangerous to humanity’s evolution. What we learn from the authors’ descriptive language is that Jordan’s idea and scope of humanity reaches beyond her birth country, as evidenced in her tireless interest in Nicaragua, Lebanon and Palestine; in those who suffered the ills of oppression and in what I would call the burdens of social structures that bind us to a way of living within the contours of racial identity and the body politic. Jordan believed poetry had the power to teach and educate, and she did not shy away from difficult word choices to appease the working class.

This ideology is explored in Maria Poblet’s essay “Puño en Alto! Libro Abierto!/ First Up! Book Open!: On Anti-Intellectualism, Literacy Brigades, and Revolutionary Consciousness.” Responding to a conversation between teacher and student in which Poblet thought poetry should be easy to read for members of the working class who had little to no education, Jordan offered, “Have you ever asked a working class teenager if she would rather be fed easier words or get an education that allows her to read any word she wants?” As a former student heavily influenced by Jordan, Poblet offers in reflection, “as we face the crisis of today, I am drawn to June Jordan’s wisdom, and her passion for deeply human critical consciousness.”

The section “We Are Lucky She Dared” includes “Some of Us Did Not Die,” a thoughtful essay by the poet E. Ethelbert Miller, a longtime friend of Jordan’s who sketches an intimate perspective. Critical to this section is how he separates the body of Jordan’s work into nine categories: The Middle East, Black studies and Black English, her fight against cancer, prison and police violence, international affairs, bisexuality, New York (Harlem and Brooklyn), love poems and humor.

Miller’s view is up close and personal, providing the reader with private antidotes while examining her poems and correlating them to geopolitical issues. In his analysis of “Moving Towards Home,” Miller highlights stanzas such as:

I was born a black woman

And now

I am become a Palestine

Against the relentless laughter of evil

Want more sharp takes on politics? Sign up for our free newsletter, Standing Room Only, written by Amanda Marcotte, now also a weekly show on YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

Many of Jordan’s former students highlighted in this anthology come from her famed course Poetry for the People, which she taught at the University of California, Berkeley. In the essay “Between the Knuckle of My Own Two Hands: Learning from June Jordan,” Sriram Shamasunder writes about taking this famed class toward the end of Jordan’s battle with cancer and how the experience impacted her. “The class,” Shamasunder writes, “made me feel like I had something to say.” She then retells the story of going to Jordan’s home after there had been rumblings of students criticizing Jordan on campus for not “sufficiently” standing up for the rights of Palestinians. Shamasunder provides the reader a glimpse of how this sentiment affected Jordan, in that these students were too young to understand the totality of the poet’s commitment to justice and the sacrifices she had to suffer — most notably, when she wrote “Apologies to the People of Lebanon” and was basically censured by the press and media for years.

In “The Awesome Difficult, Work of Love,” the anthology’s third and final section, a conversation between Angela Y. Davis, Prathiba Parma and Leigh Raiford places Jordan in even greater context. As Raiford, a professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, eloquently explains, the conversation is “an opportunity to learn together the depth of her radical commitments, the incisiveness of her pen, and the expansiveness of her vision of liberation.” As a poet, this conversation helped me understand Jordan in her full, complete humanity. The love for Jordan, and what she believed in, is not only on display in this conversation, but also throughout the book itself — through friends, confidants and admirers of her work.

In a time when this world needs more love, compassion, empathy and voices who will speak for the different, the other, the voiceless, we should look more at the career and life of June Jordan, who understood the assignment of being human. But more than that, Jordan was willing to fight for what she believed in, and damn the consequences — because right knows no wrong. “This Unruly Witness: June Jordan’s Legacy” is perfect for anyone looking for a way to embrace morality while calling out injustice.

This anthology left me humbled — and determined to double down on my commitment as a writer, a free thinker, a humanist. As a society, we often neglect and forget the way in which societal structures coexist within the idea of oppression itself — especially within the United States. Davis places this conviction in context when she writes, “in many ways, the world is catching up to June. And perhaps also catching up with an awareness of the relationship between one’s person and political life, one’s capacity to engage in self-care.”

I cannot have read “This Unruly Witness: June Jordan’s Legacy,” and fail to ask myself as poet, writer and human the following question during this current political climate: What would June do?

Read more

about this topic