For Black Ballerinas, Painting Ballet Slippers Is a Tedious But Essential Ritual

Of all the circles of women I’ve been lucky to join over the years, perhaps the most precious one was on the floor of a Black dance studio in Austin, TX. While our 3-year-old girls practiced their gummy plies to music from The Princess and the Frog soundtrack in preparation for their first recital, we mothers sat cross-legged to the side, holding our plastic bags filled with makeup sponges and $2.95 bottles of drugstore makeup foundation. At the time, there were no brown shoes for our little ballerinas. Everything, everywhere, “ballet pink.” So, it was on us to make sure that when they went on stage, the sweet thru line of their bodies went uninterrupted by a false flesh tone. Even if the world didn’t intuitively see our girls as ballerinas, we could still protect their tender images of self.

Their teacher China Smith, who first opened Ballet Afrique in 2008, didn’t take her first ballet class until college, because she grew up believing that ballet belonged exclusively to the rich white girls who lived on the other side of the highway. She walked us mothers through the long-practiced ritual of pancaking shoes. As I chatted with the women, our heads bowed in sacred task, every dab of the sponge between the toe crevices, or around the delicate heel of a ballet shoe, felt like a deeply deliberate honoring.

An adoptive mother, I was the only white woman in the studio that day. Twice a week since the time she could walk, my daughter danced with other Black children whose parents also worked their hair into plaits and twists, kept lotion in the car, and fought for spaces in which their children were lifted up as beautiful and belonging. Dance further provided my daughter with the reliable opportunity to see me as the minority in the room for a change. Transracial adoption is a risky undertaking with so many ways to fail a vulnerable child. I do believe that of all my efforts to do right by my Black daughters, and to provide a somewhat stable scaffolding for their own self-actualization, signing them up for dance classes, and the gift of community that came with them, was our greatest win.

The ritual of pancaking shoes and hand-dying tights began in the early 1970s, in another sacred space for Black dancers. Arthur Mitchell set out to shock the world when he founded Dance Theatre of Harlem in 1969, disproving the long-held notion that the Black body and spirit didn’t belong on the classical stage. When the professional company first started touring, the ballerinas still performed in pointe shoes that came in “ballet pink” or “European pink.” Ballerinas had always swathed their legs and feet in pale iridescence to lengthen their line and enhance the illusion of floating on their toes without any shoes.

Dance Theatre of Harlem ballerina Llanchie Stevenson first sparked the change. While dancing in the corps in the National Ballet, she’d taken to dying the straps of her tutu brown so the pale slashes of fabric wouldn’t interfere with the line of her neck and shoulders. Now with Mitchell’s approval, she took further charge of her line by layering brown tights with the feet cut off on top of her ballet pinks at the start of company class. “Wait, now my arms match my legs!” Stevenson told me, describing the psychological joy of finally seeing her body in the studio mirrors as one precious whole. “All of the sudden, I’m connected. I’m one body, instead of halves. Soon I couldn’t rehearse without them. I couldn’t do three pirouettes on pointe if I wasn’t in my brown tights.”

Later, Dance Theatre of Harlem would begin a European tour in pink tights and end it in flesh tones, declaring to the world that the lines of the Black body deserved the same care and respect as their white peers. Once back in New York, the dancers began the sacred process of going through their wardrobe mistress Zelda Wynn’s colors of dye and tea leaves to find their own unique shade. Before every performance, they would use makeup powder on their shoes to ensure they still matched their tights exactly, just in case a snatch of pink had started peeking out from beneath their dye. After every show, they would shellac or Future floor wax inside their shoes and around the box and shank and let them dry and reharden overnight. The labor of dying and redyeing shoes, which ballerinas burn through like brush, was tedious and constant. But the ritual was an essential one; it staked a Black ballerina’s right to her artistry.

Even as companies have begun offering a wider variety of hues of tights and shoes in recent years, the ballet aesthetic remains resolutely fixed on the ideal of the white sylph. When my daughter was in a fine arts academy middle school, her teacher sent home a letter to parents, requesting that the girls all have “ballet pink” shoes in time for the end-of-year show. I immediately wrote back asking if she meant flesh-tone, because I would not in fact be disconnecting my daughters’ feet from her form. The teacher was embarrassed and corrected her mistake. She hadn’t meant to forget the fact of my daughter’s Blackness. She just hadn’t been thinking about her when speaking generally about the dancers. That’s what it can be like to be “the only” in a room. You’re rendered unspecific or invisible, smudged out of the picture.

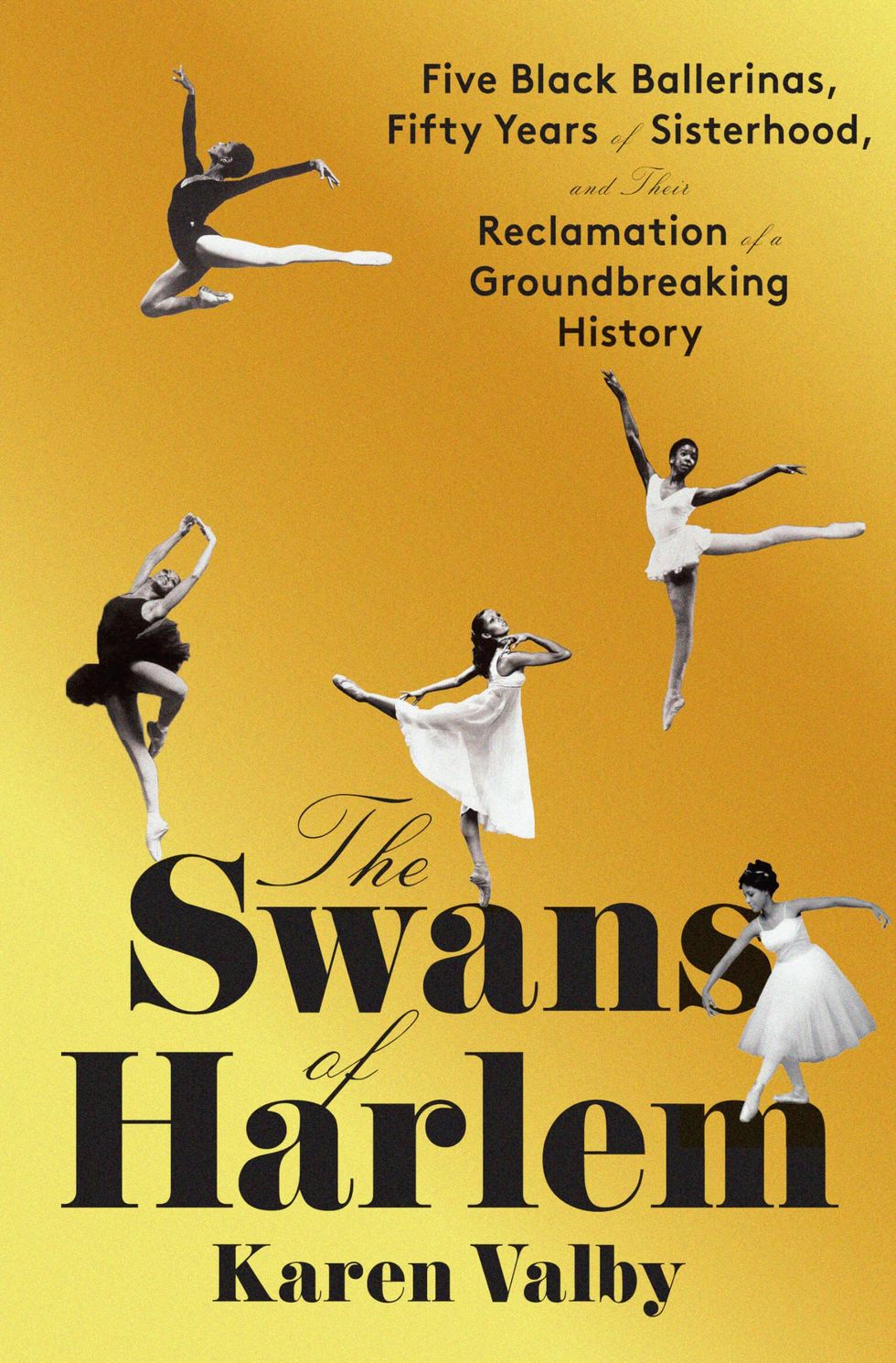

When I told an acquaintance that I’d written a book about five of the founding and first-generation Dance Theatre of Harlem ballerinas, she seemed genuinely confused. “You never see Black ballerinas, do you?” (I do.) “Maybe because of their body types? Their muscles and curves. Well, I guess there’s Misty Copeland.”

Last year, Copeland launched a petition on her Instagram page urging Apple to introduce a range of shades for the pointe shoe emoji. She’s since amassed more than 54,200 signatures of support, as well as critics who argue that she’s micromanaging something meaningless, wrongly bringing race into something as trite and innocent as a pair of satin shoes. “This petition isn’t just about an emoji,” insisted Copeland, American Ballet Theater’s first and only Black principal ballerina in the company’s 85-year history. “It’s about ensuring the art of ballet, in all its forms, celebrates every dancer’s story and shade.”

Expanding the aesthetic of ballet is not an abandonment of tradition. It is a vital act of inclusion and expansion. It foresees a future for ballet that is vibrant and curious and full. It’s about circles growing larger, rather than diminishing into sameness and oblivion. Spring recital season is once again upon us. Who do we expect to see on stage?