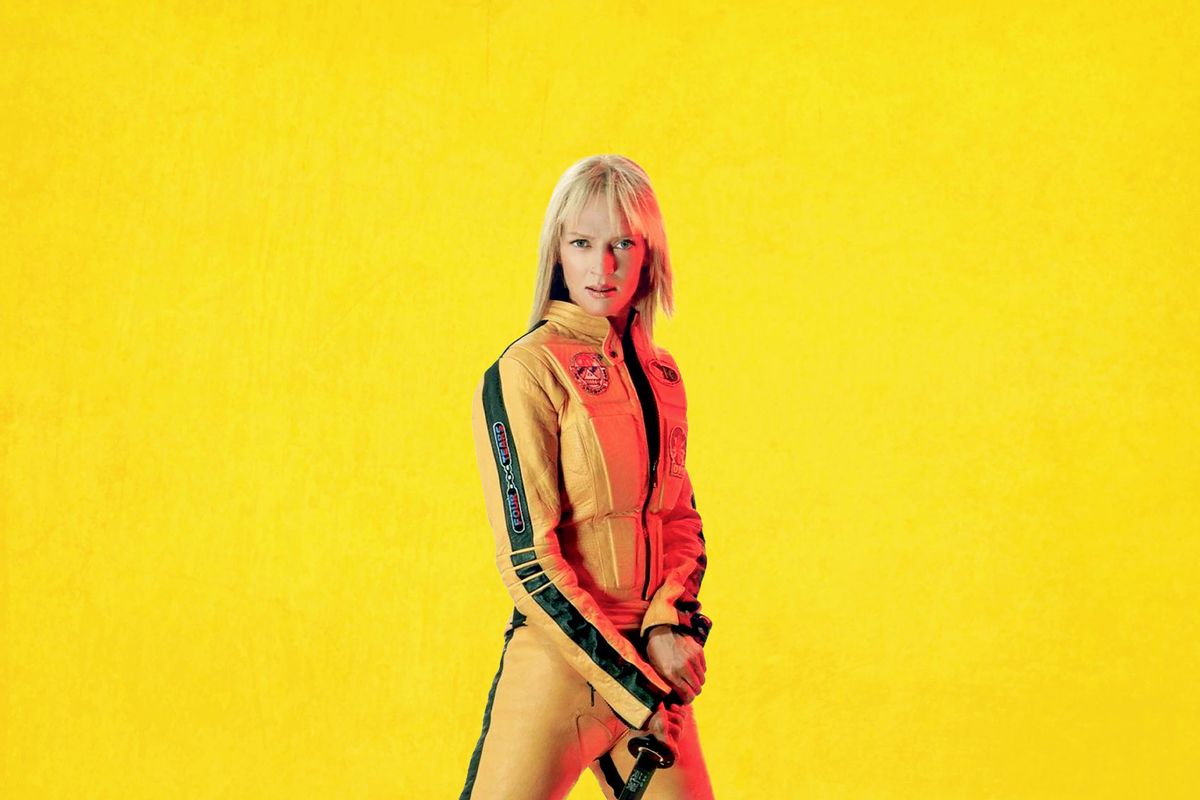

Twenty years after “Kill Bill” came out, The Bride’s bloody rampage cuts differently

Twenty years ago, if you had asked me whether “Kill Bill: Volume 1” would become a go-to rewatch, I would have rolled my eyes violently enough to cause a headache. Nearly everything about it screamed macho indulgence of a stripe now codified as “Tarantinoesque,” beginning with a runtime that was, in its day, excessive at 111 minutes.

A movie you watch when all you want to do is cut a B, but recognize that stewing on your couch in the comfort of home is better than catching a case.

Much of that consisted of a parade of ‘70s and ‘80s midnight movie tributes and Hong Kong action flick legends including Sonny Chiba and Gordon Liu, interrupted by an anime flashback that never . . . seemed . . . to end. As a fan of all these genres, I should have immediately taken to the adventures of Beatrix Kiddo, initially only known as The Bride – a creation credited to Q & U, or Quentin Tarantino and Uma Thurman, its star.

For an array of reasons anyone worn out by culturally overcompensating hipsters probably understand, it took a while. About as long, I’d say, as it took for fanboys to realize that their ability to cite all the cinematic references that made “Kill Bill” the ultimate movie homage to movies was neither impressive nor the stuff of scintillating small talk.

That was less of a factor than the natural progression of life, the shuddering inevitability of sustaining betrayal, humiliating loss or chilly loneliness. Whatever that turn of events was, The Bride’s defiant drive to roar, rampage and get bloody satisfaction became a go-to release valve. A movie you watch when all you want to do is cut a B, but recognize that stewing on your couch in the comfort of home is better than catching a case.

Everyone has one of those, and if they tell you they don’t, they’re either lying or lacking a list of worthwhile viewing suggestions; either way, if they don’t, they should.

“Kill Bill: Volume 1” has less value in the long run as a cinematic scrapbook than for the naked emotional honesty Thurman brings to The Bride – first as a survivor of rape and assault, then as a mother whose child was taken from her along with four years of her life. She was betrayed by her chosen family, the people she trusted the most, who also robbed her of a new circle that was caring and supportive . . . as far as one can tell before the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad murdered them all.

It wasn’t merely that Bill, the man she used to love and left (revealed to be David Carradine in the second movie), took out his rage on these innocent strangers. The women who participated in the group jump out – Vernita Green, aka Copperhead (Vivica A. Fox); O-Ren Ishii, aka Cottonmouth (Lucy Liu) and Elle Driver, California Mountain Snake (Daryl Hannah) – joined in gleefully, and their sinister grins as she blacked out are in some ways a worse affront than Bill’s deadly malice.

Mix all of it with Thurman’s performance, and the whole four hours and eight minutes becomes a stellar exercise in female catharsis. Just not a perfectly defensible one – not anymore.

If you think of some movies as old friends, then it follows that like most friendships between people, our bonds aren’t always unconditional. They may serve us for a season, and then we outgrow them. Conversely, some transform as we change, enabling fresh interpretations to emerge and shading our perspective in new ways.

It occurred to me recently that I hadn’t watched “Kill Bill: Vol. 1 and 2: since 2018, when Uma Thurman finally opened up to the New York Times’ Maureen Dowd about the abuses she endured on her way to making what many consider to be Tarantino’s opus – and during its production. In this profile Thurman revealed herself to be one of Harvey Weinstein’s victims and admitted to feeling bad about all the women who were attacked after she was.

“I am one of the reasons that a young girl would walk into his room alone, the way I did,” Thurman said. “Quentin used Harvey as the executive producer of ‘Kill Bill,’ a movie that symbolizes female empowerment. And all these lambs walked into slaughter because they were convinced nobody rises to such a position who would do something illegal to you, but they do.”

Dowd’s profile also breaks a heretofore never-revealed account about a sequence where The Bride is shown driving what turned out to be a mechanically unsound Karmann Ghia on her way to fulfill the title’s promise. She asked Tarantino to use a stunt double, expressing her concern that the car wouldn’t drive correctly, and he bullied her into getting behind the wheel anyway. It crashed, and the footage of that moment is bone-chilling.

She and Tarantino fought for years afterward, and though he finally handed over the raw footage of the incident to her 15 years later, that was long after she says Miramax and Weinstein swept it under the rug. In an Instagram post that Thurman released after the story ran, she said that Tarantino is “deeply regretful and remains remorseful about this sorry event,” later adding, “. . . THE COVER UP after the fact is UNFORGIVABLE. for this i hold [film producers] Lawrence Bender, E. Bennett Walsh, and the notorious Harvey Weinstein solely responsible.”

Several shattering pop cultural events have demanded that we reevaluate our relationship with works of art woven into our lives and, more than this, our identities.

For many years after its release, “Kill Bill” and Thurman’s Beatrix Kiddo were held up as symbols of female empowerment, much in the way Buffy Summers, Sydney Bristow, and Xena were. Generation X’s Third Wave feminists treasured those characters for fulfilling our view of what a woman’s physical power and prowess can look like. They still do, albeit with caveats – starting with the fact that all these characters were created by men. Thurman collaborated on The Bride, but the film itself is as Tarantino as his oeuvre gets.

Putting aside the debate about how feminist a character can be when her existence, personality and quest are all informed by a man, what altered my esteem for “Kill Bill” are the circumstances behind what is otherwise a benign driving shot.

Thurman collaborated on The Bride, but the film itself is as Tarantino as his oeuvre gets.

Once I knew about that, I couldn’t refrain from viewing another “Volume 1” scene differently, the one where The Bride is being strangled by a chain. Thurman’s face visibly reddens as the blood flow is cut off, letting us know that her discomfort is real.

And Tarantino was pulling that chain, a flourish to which Thurman consented, as she did in a “Volume 2” scene where Madsen’s Budd spits on The Bride. My mind travels back to those self-satisfied film obsessives marveling at male genius, and how they would have praised both Tarantino for his commitment to artistic realism and Thurman for gamely playing along.

Another way of describing that is . . . compromise.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

It is not for me to presume whether Thurman would agree with the stinging disempowerment implied by that term. It’s not her place to tell me or any other viewer to refrain from interpreting the context thusly. But that thought angers me on her behalf, with empathy for what she went through.

At some point I’ll watch “Kill Bill: Vol. 1 & Vol. 2” again, with a new understanding of what went into making this classic along with additional respect for Thurman, and an appreciation of the wisdom she gained from her healing process.

“Personally, it has taken me 47 years to stop calling people who are mean to you ‘in love’ with you,” she told Dowd. “It took a long time because I think that as little girls we are conditioned to believe that cruelty and love somehow have a connection and that is like the sort of era that we need to evolve out of.”

Yes, this – along with evolving our concept of what a strong, determined woman of action looks like onscreen. Every woman lead of an act produced after “Kill Bill” – Zoe Saldana, Charlize Theron, Angelina Jolie, and others – owes a debt to Thurman’s elegant, focused screen rampage.

And every woman who takes a vicarious thrill in this now 20-year-old cultural legend should also appreciate the fortitude it required for its star to swallow her own rage for many years, so as not to assassinate the fantasy of every inspiration its fans saw in it and everything they needed it to be.

Read more

about this topic