UK’s nuclear fusion site ends experiments after 40 years

“It felt brilliant. One thing is to work on a design, another thing is to operate it.”

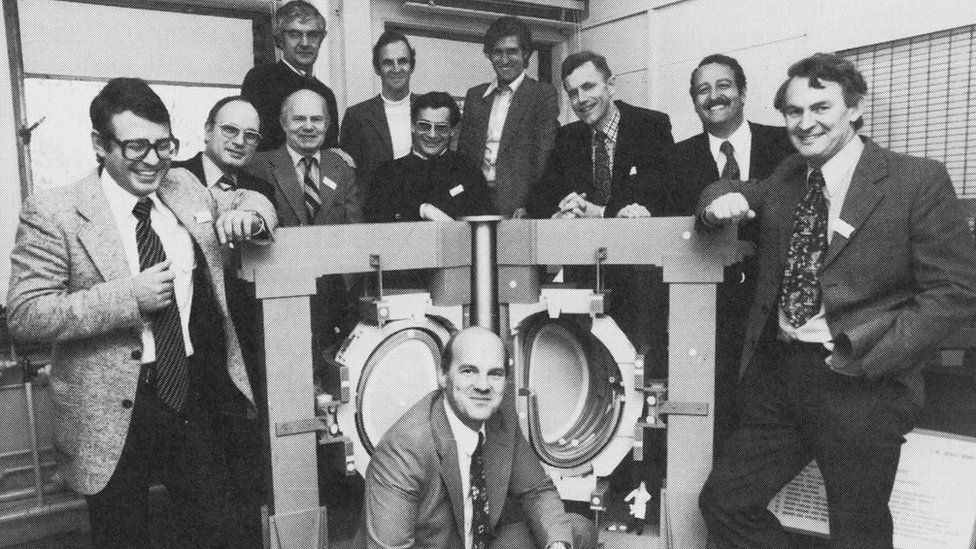

Professor Barry Green recounts the moment in June 1983 when the JET fusion laboratory in Oxford undertook its first experiment.

For the next four decades, the European project pursued nuclear fusion and the promise of near-limitless clean energy.

But on Saturday the world’s most successful reactor will end its last test.

Nuclear fusion was “discovered” in the 1920s and the subsequent years of research focused on developing fusion for nuclear weapons.

In 1958, when the United States’ war research on fusion was declassified, it sent Russia, UK, Europe, Japan and the US on a race to develop fusion reactions for energy provision.

Fusion is considered the holy grail of energy production as it releases a lot of energy without any greenhouse gas emissions.

It is the process that powers the Sun and other stars. It works by taking pairs of light atoms and forcing them together – the opposite of nuclear fission, where heavy atoms are split apart.

The UK and the Europeans decided to pair up and from that the Joint European Torus (JET) site was born. Scientists were brought in from across the continent to Culham in Oxfordshire; Professor Green was one of them.

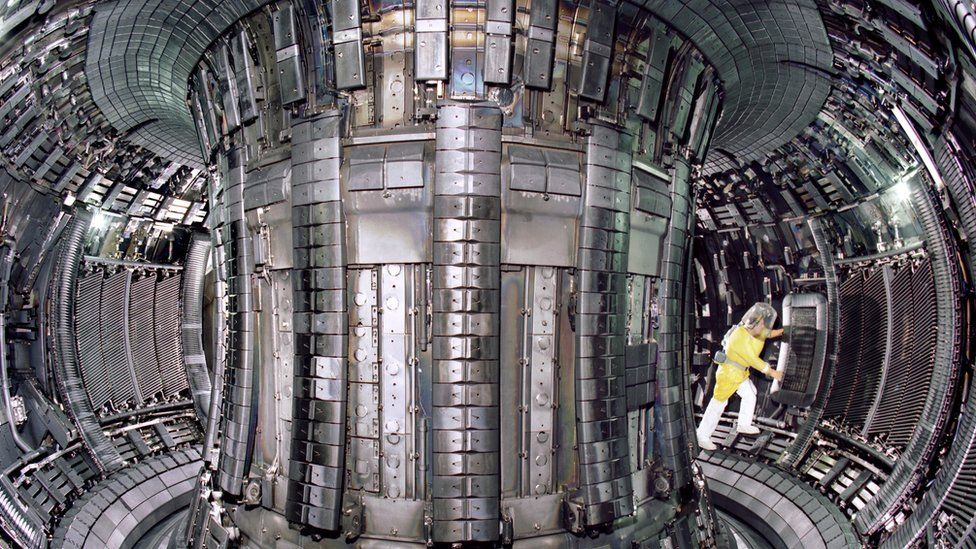

An Australian working on plasma physics in Germany, he became lead engineer at the site, overseeing its design and construction. The chosen model was tokamak, which uses magnetic fields to confine the plasma – a hot, ionised gas – inside a vessel. This plasma allows the light elements to fuse and yield energy.

It was also designed to work with a mix of deuterium-tritium – radioactive elements of hydrogen – rather than just one, which proved a crucial decision. It has been identified as the most efficient reaction for fusion reactors.

The first experiment in the world with this fuel mix took place at JET in 1991. Subsequent experiments have achieved higher energy yields, and the site holds the world record for the most energy produced from a fusion experiment – 59 megajoules (MJ) during a five-second pulse.

Despite the records, the JET site faced many difficulties and delays, with experiments suspended for nearly a decade in the mid-2000s while the internal structure was replaced, according to Fernanda Rimini, JET senior exploitation manager.

And the hope of producing enough energy to power homes remains a long way off – 59 MJ is only enough to boil about 60 kettles’ worth of water.

Joelle Mailloux is the JET science programme leader overseeing the third round of deuterium-tritium experiments which end on Saturday.

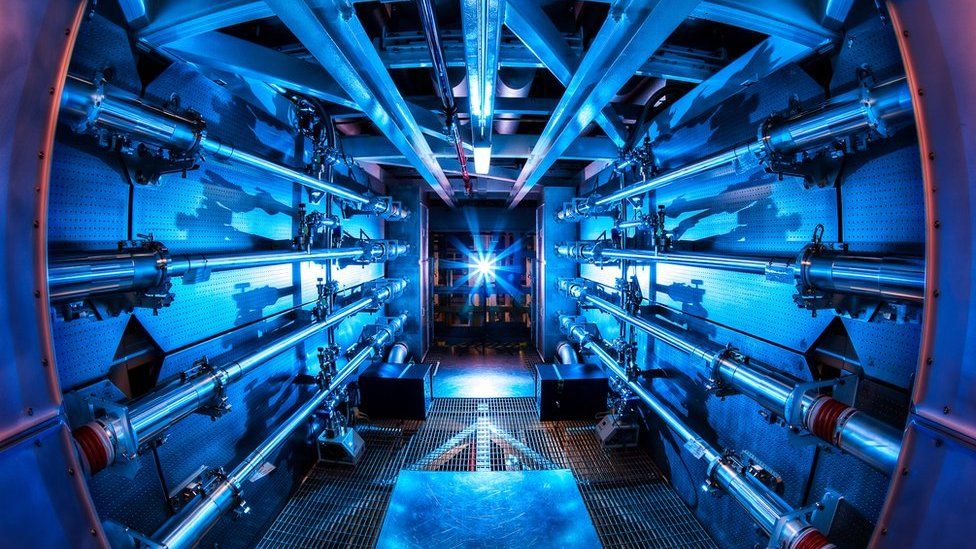

She says the key challenges they are focusing on are making the plasma more stable, spreading the power load and looking at improving materials in the reactor to withstand the conditions.

Once the experiments end, scientists will still have a lot to learn from JET.

“The decommissioning will look at analysing what has happened to the [reactor] materials and how they have changed. This will help better maintain other fusion sites,” Ms Rimini said.

One of the site’s benefiting from JET’s research will be the new Iter reactor in southern France. It is the world’s largest fusion project and is a consortium of many countries including the EU, Russia, the US and China – but a few weeks ago the UK government confirmed the UK would not play a role.

“In line with the preferences of the UK fusion sector, the UK has decided to pursue a domestic fusion energy strategy instead of associating with the EU’s Euratom programme,” the government said.

The UK government has committed to spending £650m on an alternative UK fusion programme between now and 2027. This includes a new prototype fusion energy plant in Nottinghamshire called STEP.

Paul Methven, STEP programme director at the UK Atomic Energy Agency, told the BBC: “On endeavours like this, you need to be simultaneously really ambitious and also realistic.

“We are driving pretty hard towards our first operations to be in the early 2040s.”

Related Topics

-

-

6 October 2022

-

-

-

9 February 2022

-

-

-

13 December 2022

-