“Taiwanese food is an underdog”: In her new cookbook, Clarissa Wei writes a love letter to Taiwan

Clarissa Wei’s Taiwanese pride is unmistakable.

Her new cookbook is actually so much more than just a standard cookbook: It is a love letter to Taiwan, its culture, its history, its perseverance and, of course, its cuisine.

As Wei puts it, there’s a minimalism about Taiwanese food that she both cherishes and appreciates, which bridges the historic, storied cuisine with the ease of a weeknight meal: “If you can whip up an entire meal with just a wok, knife, soy sauce and sugar,” she states.

Salon Food spoke with Wei in accordance with the release of this new cookbook, discussing the recipes itself, Taiwanese cuisine at large, what was most important to her in creating the book and so much more.

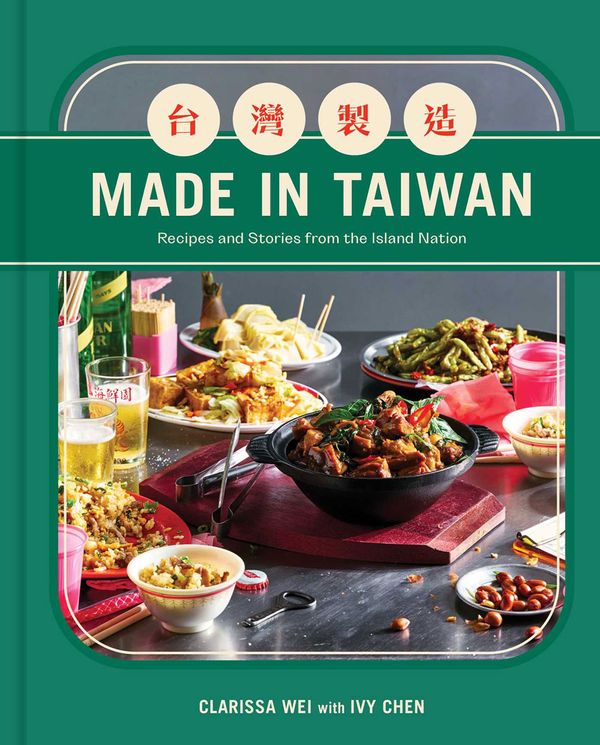

Made in Taiwan by Clarissa Wei book cover (Courtesy of Simon Element / Simon & Schuster)

Made in Taiwan by Clarissa Wei book cover (Courtesy of Simon Element / Simon & Schuster)

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

“Wei makes a case for why Taiwanese food should get its own spotlight” — I loved this quote. What about Taiwanese food has ostensibly made it an “underdog” in the global food spotlight?

Taiwanese food is an underdog because it is often grouped underneath the broad umbrella of Chinese food. Part of the reason why that is was because in the 60s and 70s, Taiwan was portrayed as a rich hub of regional Chinese food. This was true to some extent because of the surge of Chinese refugees who had arrived in Taiwan post-1949 with the Nationalist government. They brought with them vibrant recipes from a diverse group of Chinese provinces. The refugees only made up 10 to 15% of the population, but their food and culture shaped the international perception of Taiwan.

A lot has happened since then and over 70 years have passed since that last wave of immigration. Taiwan transitioned from authoritarian state under martial law into a democracy and with that there’s been a major shift in how Taiwanese people perceive their food. Even the flavors of those regional Chinese restaurants have changed to be more Taiwanese (sweeter, lighter and less heavy on salt and spicy notes).

I wrote this book in the hopes of broadening the international perception of Taiwanese food. Yes, we have dumplings and noodles and fried rice, but we also have wonderful dishes that are special to the island, like fried mackerel soup, savory rice puddings and crystal meatballs.

What are some of the standout recipes in the book? Or your personal favorites?

I love the beef noodle soup recipe. It’s a bit involved because of all the spices in there, but it is also quite restrained in that it allows the natural flavor of the broth and beef to come through. I got the recipe from a five-time award-winning beef noodle soup chef and it is a recipe he teaches his students.

I also really enjoyed writing the stinky tofu recipe. It took us a while, but my recipe developer Ivy and I figured out how to make the dish from scratch. The secret to the stink is a leafy green called amaranth.

How would you describe Taiwanese cuisine to someone completely unfamiliar with it?

Taiwanese food is hearty and sweet, mostly grounded in pork, seafood and rice. I’d also describe it as a melting pot. We have influences from China, Japan and even America.

This is so much more than just a cookbook. What do you hope readers glean from the incredibly comprehensive book of recipes, stories, pride, perseverance and recollection?

Thank you! Even though Taiwan may look like an ethnically homogenous society from the outside, it is actually quite diverse. This applies to the food. With every different wave of immigration and governance has come a plethora of new dishes. The food brought over by Chinese immigrants from southeast China from the 18th century, for example, is very different from the food brought over by Chinese immigrants from the 20th century after the Chinese Civil War. Also in the 20th century, Japan monopolized most of Taiwan’s major industries. Many of our pantry items like soy sauce, rice wine and rice vinegar are still made with Japanese-era recipes.

I hope through the food of Taiwan, people can learn more about the history of Taiwan.

Can you briefly tell me a bit about the essays in the book, their general thesis and what they touch on?

So every time after I finish watching a movie, I’ll immediately pull up my phone and look up fun facts about the movie. I love reading esoteric tidbits about the production, plot and cast.

I wanted the essays in my cookbook to provide that same function. They’re fun facts about Taiwanese cuisine that most people don’t know about. Some of the topics are heavy, like how American aid during the Cold War shaped Taiwanese food culture or on the politics of the island. Others are more lighthearted, like how to shop at a wet market or how to feed the Gods.

I know that you worked as a freelance journalist prior to publishing the cookbook. What was the turning point that made you want to focus on Taiwanese food and culture beyond daily news?

I’ve been a food journalist for well over a decade. I lived in Hong Kong from 2018 and 2020 and was there throughout the pro-democracy protests. My job at that time was to film food and culture videos in China and Hong Kong. In China, there was this distinct sense of optimism and nationalism. People were proud to be Chinese and to showcase their rich culture and food. In Hong Kong, there was pride, but there was a clear existential crisis that people were facing because of all the political upheaval.

Naturally, as a Taiwanese citizen, I couldn’t help but wonder if Taiwan would one day face a similar fate as Hong Kong. I wanted to tell the story of Taiwan through the lens of food before it’s too late.

Clarissa Wei (Photo by Ryan Chen)

Clarissa Wei (Photo by Ryan Chen)

I read on your website that the book was “shot and written entirely in Taiwan by an all-Taiwanese team.” How incredible! What was it like putting that team together?

First of all, I had an incredible editor who let me bring on whoever I wanted to, which isn’t always the case in the industry. Because I’m based in Taiwan, I knew immediately I wanted an all-Taiwanese team. Second, I got really lucky. My recipe developer Ivy Chen is a cooking teacher in Taipei whose classes I’ve attended many times before and we’ve always had a really good rapport. My researcher Xin Yun slid into my DMs one day out of the blue asking if I needed an assistant. I hired her immediately and she was the one who found my food stylist (Yen Wei) and photographer (Ryan Chen).

My team and I got along really well and without even talking about it, we all collectively felt this immense pressure to represent the food of Taiwan as best as we could. None of us had ever worked on a book by a major publisher before and we treated this like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I was the only person in my team who was not born and raised in Taiwan and I learned so much from them.

Want more great food writing and recipes? Subscribe to Salon Food’s newsletter, The Bite.

I know that you hired a Taiwanese historian to fact check the essays. Tell me a bit more about that?

There’s not a lot of mainstream books on Taiwanese history in English— let alone on Taiwanese cuisine. Most of my research was derived from academic articles, books published solely in Chinese or books that had been translated into English from Chinese. I had a couple other writers read through the essays for feedback and my researcher did some basic fact-checking throughout, but because the history of Taiwan can be controversial, I knew I needed someone who specialized in Taiwanese history to go through it one final time.

I asked James Lin, who is a Taiwanese historian and a professor at the University of Washington, to look over the main essays in the beginning of my book. There weren’t big structural changes, but he gave me suggestions on how to be more precise with my words (i.e. Taiwan was inhabited by Austronesian nations, not tribes). He was incredibly helpful and I’m so grateful he said yes!

You tweeted the other day about how “review bobbing” is beginning already. What do you attribute that to?

It’s just the reality of being Taiwanese and it is unfortunate that the very act of being Taiwanese is controversial. There are two main things that people get mad at me about: that I dare call Taiwan an island nation (Taiwan is a self-ruled democracy, but exists in a state of political ambiguity. I have an entire essay in the book that details why) and that I say that Taiwanese food is not a subset of Chinese cuisine (my book is a reflection of recent identity polls in Taiwan).

Sometimes I wonder if I’d get the same amount of vitriol if I weren’t Taiwanese and wrote this cookbook as an outsider. The Chinese government actively uses Chinese ancestry as reason to extend its authoritarian rule over the Chinese diaspora. Because I am ethnically Chinese (my ancestors came to Taiwan from China over 200 years ago!), I’ve been called a traitor and disrespectful to the Chinese nation by online trolls. It’s really bewildering.

What are your absolute favorite aspects about Taiwanese cuisine?

It’s quite minimalistic. If you can whip up an entire meal with just a wok, knife, soy sauce and sugar.

Traditional Taiwanese dishes (Yen Wei/Ryan Chen/Simon Element/Simon & Schuster)

Traditional Taiwanese dishes (Yen Wei/Ryan Chen/Simon Element/Simon & Schuster)

You include a note in the beginning of the book about “language and romanization.” Can you explain a bit about that?

While Mandarin Chinese is the lingua franca here in Taiwan, there are some dishes in Taiwan that are known exclusively by their Taiwanese Hokkien names. I made sure to include that where relevant because people in Taiwan would get really upset if I just listed everything in Mandarin. I hired Cam Chao, a translator, to help me with the Taiwanese translation of dishes.

What are some must-have ingredients or products for anyone looking to start making Taiwanese dishes?

Soy paste, which is a condiment invented in Taiwan. It’s a thickened soy sauce. It has the texture of oyster sauce but without any of the fishy undertones. I use Kimlan brand. It forms the basis of a lot of the dipping sauces in the cuisine.

Also, fried shallots! This is something that can be added in braises for extra flavor or thrown on top of stir-fries for crunch.

I liked how one section or chapter was called “beer food” — how would you define that?

The equivalent is izakaya food in Japan or pub food in the UK. It’s greasy, hearty, flavorful dishes and meant to be paired with an ice cold lager. Think clams sauteed with basil, three cup chicken and deep-fried green beans. Taiwanese beer food, or rechao, became a popular genre in the 80s and 90s. It’s not that well-known outside of Taiwan, unfortunately, but is my favorite way to unwind after a long week at work.

Another section is called Tainan; what does that represent?

A city in the south of Taiwan, Tainan is where my family is from, where my recipe developer Ivy is from and where my food stylist and photographer currently live. It’s also the culinary capital of Taiwan and the oldest city on the island. There are a lot of dishes unique to Tainan that I wanted to highlight, like the fried shrimp rolls, coffin bread and the oyster omelets.

It would be a great disservice if I skipped over Tainan and its dishes. It’d be like writing about the food of California and forgetting to include Los Angeles. Even though my cookbook is catered to a general American audience, I wrote my cookbook with discerning Taiwanese readers in mind.

You can buy “Made in Taiwan: Recipes and Stories from the Island Nation” here.

Read more

about this topic