“Comics are not covered like other artists”: How Ali Siddiq changed the system to own his jokes

The concept of hitting the road as an undiscovered comic, grinding out shows and hopefully capturing the attention of some Netflix, HBO or Hulu executive along the way, is a pipe dream. Even so, a network special does not guarantee a comedian long-term success — if you define it like comedian Ali Siddiq does — owning your own work. “If somebody comes to me with $30 million, it is still going to be a conversation about ownership,” he said on “Salon Talks.”

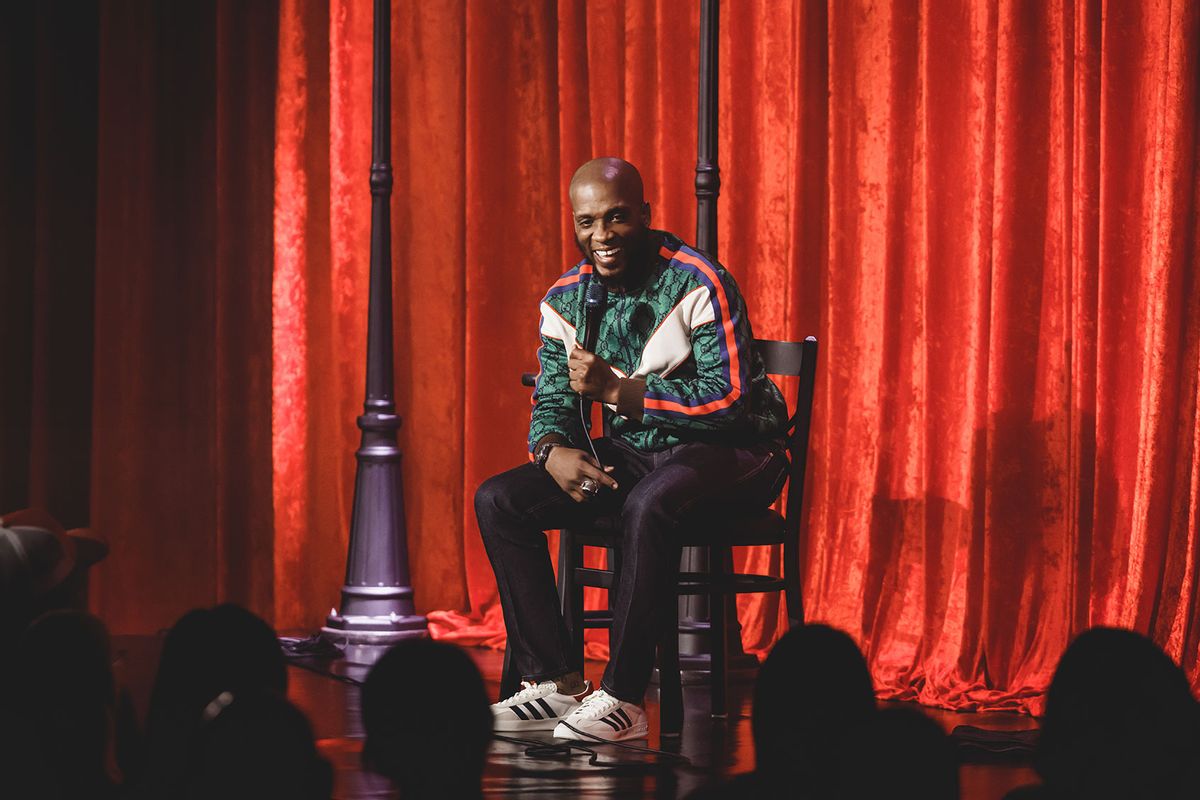

Many remember Siddiq from his appearances on HBO’s “Def Comedy Jam” and “Live From Gotham.” Those performances led him to be named Comedy Central’s No.1 Comic to Watch. Later, he recorded a one-hour special for Comedy Central in the Texas jail where he once served time called “Ali Siddiq: It’s Bigger Than These Bars.”

Siddiq explained to me during our conversation that he didn’t get his real breakthrough until he tried to promote “It’s Bigger Than These Bars” on his Instagram account by sharing a clip. Instagram removed the clip for copyright infringement, which means Siddiq wasn’t allowed to share a video of himself because he did not own that content. As a result, he went totally independent.

Siddiq financed his own stand-up, “The Domino Effect,” which received over 9 million views on YouTube. “The Domino Effect 2: Loss” is out now and projected to do more, with all of the proceeds going to Siddiq and his team. The networks are watching, but Siddiq can sit back and engage them when he is ready.

Watch my “Salon Talks” episode with Ali Siddiq here or read a Q&A of our conversation below to learn more about his business approach, how he developed his storytelling style of comedy and why he wants to be known for stand-up above all else.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

You are redefining the way comedians are putting their work out into the world with “The Domino Effect Part 1” and “Part 2: Loss.” You’re cutting the middleman out, and everybody comes straight to you. Why did you decide to release it on YouTube?

I always wished that these were very complex things, [like] it was a bunch of real thought into it. With me, I posted a clip of me on Comedy Central on Instagram and I got flagged for copyright infringement. I was like, “Wait a minute, I can’t promote that I have this special on your network, I can’t do that?” Then with Instagram you don’t have nobody that you can call and say, “Hey yo, this is me.” With Facebook it’s not a phone call, which is irritating, that you just can’t say, “Yo, this is actually my work, this is who I am.”

It’s like going to the tow truck place where they tow your car and you walk in there like, “Hey do you all have a burgundy Lexus in here?” “How do we know that’s you?” Who be going around just going to random places asking for a burgundy Lexus with all my stuff inside of it? “I need your ID.” “For what?” Who else came here and said, “Hey, do you all have a burgundy Lexus with my backpack in it?”

The ID and the title and all that in the glove box.

In the glove box. With that, I said man, I have to be able to own my own stuff. That’s a lot. That’s giving a lot of power. Plus I was doing albums first. When everybody else was doing DVDs, I was doing albums. I was owning everything in my album. Then this lawsuit comes out to where a lot of our album sales and spins are getting cut from Spotify and XM Radio and all this because of a lawsuit that doesn’t serve comics well in the end, or they owe you this money for writing and producing. I think that I should get two checks if I’m the executive producer and the artist.

I don’t really need it for writing because of this. Then if I do that, then that gives you leeway to do a cover. I don’t want nobody telling my jokes and saying, “Well I tribute to Ali. I’m just doing the cover of his. I’m doing cover jokes. I’m doing cover jokes. It was 1983. Even though I wasn’t born, it was 1983.” That’s crazy to think about it. I just wanted to own my own stuff.

It sounds wild when you say that, but with the internet, somebody actually will try to cover your work and get a little following off of it. It could actually happen.

I get a clip right of this white lady on a truck mimicking — my joke is playing in the back, and she’s acting it out. It’s my Father’s Day joke. It’s all type of things that I do on the internet that people use in the background, and they just word it out and they getting followers from it. People are covering my work. Should I get paid for when they play that? I should get paid for it.

I’m always going to say yeah.

Yeah, for when they do that, but it’s like comics are not covered like other artists. But we are copyright infringed if you put out something with a network. Because of the success of “Domino Effect,” the first one, I shot the special with Comedy Central, “Bigger Than these Bars.” That’s in 2018 when it came out. It got less than a million something views because they showed it at 12:00 at night. 11:59 is the actual time that you put my special on in the middle of the night.

“I’ve always wanted to be judged on comedy content, not anything outside of the craft.”

I’m confused on the fact that you showed it once, you showed it twice. How am I supposed to get some type of burn off of that and then I can’t even promote that it’s there, for you, for people to go on your website or whatever to watch it? We asked to buy it back from them because Comedy Central is no more. They sold everything to Paramount. We asked to buy our content back. They dropped it on the internet. They dropped it on YouTube because of the success of “Domino Effect,” the first one. He hot, let’s drop his special on there now. Then when they dropped it, it got more views. It has more views now than it had when it was on the network. Netflix, HBO, their viewership versus what I can produce on my own, I beat everybody. In 2022, I beat every last one of them.

With YouTube, you can get it right to the people, no subscription needed.

You don’t make money off of the special. They pay you to do a special, then they shoot it X, Y, and Z. Your special is to push ticket sales for people to come see you and then seal your legacy in the game that you were solidified as a comic. If you got the bread, why not just do that yourself and send it straight to the people, and then still, the goal is for people to come see you. With “Domino Effect,” we got 9 million. With this new one, we on the verge of going up towards 10 million with that one, hopefully. We had 1.5 now in two weeks, so we think that the momentum will come in. More people just saw it coming to the shows because of the messaging with “Domino Effect.”

I think that I’ve reached a level now that I’m cementing what I want to be in this game. I’ve always wanted to be judged on comedy content, not anything outside of the craft. I don’t want people to say that I’m a good comic or a great comic or this type of comic because I was in a movie or because I was on a sitcom or I was on some other show that has nothing to do with stand-up. I want to be known for comedy, not anything outside of that, for somebody to say I’m a great comic because of comedy.

If an executive was to knock on your door and say, “Look man, I want you to do a special with us, I’m going to cut you a check for $30 million,” would you do it or would you not go away from what you have been doing?

“Netflix, HBO, their viewership versus what I can produce on my own, I beat everybody.”

If somebody comes to me with $30 million, it is still going to be a conversation about ownership. Because you giving me $30 million with the hope that you make $200 million. I don’t think that you giving me that $30 million with the whole thing we going to make $28 million, or we going to make $35 million. You not splitting your power with me like that. What is your end goal, and where does the material lie? Who does it rest with at the end of the day? I think that that’s why I’m so big on the legacy of my particular family and the ownership of having my children be able to license my work over somebody else owning it.

Some people can’t tell their own story because they got to go through all of these things. You ever watched a documentary, you see “courtesy of” this person? That’s because somebody had to go through a bunch of hoops in order to tell this story. I think if somebody gave me $30 million, you all would probably never see me do stand-up again because it’s going to be hard to motivated. “Hey man, hey Ali, you want to come to a set?” Man, you couldn’t pry me out my house with your cold, dead hands.

Man, I think being rich — I’m straight now. I’m not 30 million straight, but I’m telling you it’ll be hard. You would have to kidnap my children and hold them for ransom. “Hey man, come do a set in Cincinnati. We got your son. We going to release your son after your set.” I come on the stage with attitude. “Twice a year they kidnap my son for me to come do a show. This is some bulls**t. How much longer do I have?”

They like, “Yo, what’s that noise?” “That’s my helicopter that’s on top of this building waiting to take me to my jet if I can go home.” That’s the only way you going to get me.

One thing I appreciate about your style is that it’s you have the ability to speak a universal language. You’re from Texas. I’m from East Baltimore. I got friends who love your work from the Bay Area. We all know stories like the ones you tell in your stand-up. How do feel like you developed that universal language?

I’m very grounded because I talk to everybody that’s grounded. I think the universal language comes from my friends. I have close friends in Baltimore, just like I have close friends in Oakland, Philly. It’s like when we talk, we all have the same discussions. I could call my boys in Baltimore right now, any one of them and start an argument about who got the best crab cakes. This is 40 minutes of somebody naming another spot, another spot, then hanging up and calling back like, “I just thought about it. Such and such got the best . . .” That’s the thing. I live in Houston. I always argue, “Why do Baltimore think that they got the lock on crab when I live in the ocean, I live right here on the Gulf?” I’m like, “Do you all not think that the Gulf of Mexico has crab? I live in the seafood town.”

Not the blue ones.

We do have blue crab. That’s all I grew up on.

They’re not popular though.

This is the thing, and this is what Baltimore do. It’s like you going to say the same exact thing that everybody from Baltimore that I’ve ever heard.

Where they at? I want to see them. Bring them out. Where they at?

It’s like people from Baltimore, “Blue crab only exist in Baltimore.” They like “They don’t never migrate nowhere else.” It’s the ocean. If we was in Baltimore, I will move through Baltimore with you like I’m from Baltimore.

You did Comedy Factory and all that?

Yeah, I’ve always been in these places. Even when I was in the streets, I was always in these places. My man Reggie Carroll from Baltimore. This is one of the most insane people I know, the most insane people. He’s one of the craziest people I know is Reggie Carroll. They was like, “Where you from?” “Baltimore.” But then my man, Gary Monroe, one of the nicest people I know in this world from Baltimore. He was a federal agent. What made him even get into being a cop, his uncle was the dude who “The Wire” was based on.

Little Melvin.

Yeah. When I go somewhere, I’m engulfed in it. When I’m in Philly, I’m always in Germantown. I’m in the Badlands. I’m still grounded with the people that I grew up with because I think that that story is what made us and gave us the tenacity that we have. I’m still talking from that space. I’m still in that space.

“People are like, ‘Well where you get this mindset from?’ My neighborhood.”

I go to the same barbershop that I’ve always gone to, and my ear is to the words that’s always being said and sometimes I’m the only one that can say it in the space. I take that ownership of constantly speaking the same terms that I grew up with, because it’s the layman’s terms, man. People can understand what I’m saying and where I’m coming from when I’m talking about anything because I’m talking from a human aspect in whatever.

I think people are like, “Well where you get this mindset from?” My neighborhood. I said, “These are the ideologies of my neighborhood. This is not just me. This is other people that’s in my neighborhood.” When I say loss, when I’m talking about the fact that we never talk about these losses in nobody’s neighborhood, is somebody running around talking about when they lost something.

Absolutely. “All I do is win, win, win, win, win.”

Win. But the reality is, we’ve lost a lot in the just trying to get that one win, we’ve lost a lot. I don’t know any men that haven’t felt the pain of losing a girlfriend that they really was into. I don’t know the guys who never felt the pain of losing a loved one or losing a job too early. I don’t know these people that haven’t experienced that. My man right now is still, every blue moon he’ll bring up, ah man, remember I had them Cartier glasses? I lost them motherf**kers.

That hurt though. That hurt though.

That hurt. He lost them glasses 11 years ago and he still . . . I had these Carrera shades. I’m in the Bahamas, and this lady hat blew and I reached to grab her hat and when I reached to grab it, I bent down and my goddamn shades fell in the ocean. I always remember, I said, “Goddamn.”

$320 in the ocean. Even though I’ve had better shades, I still bring up, “Man, remember that day I was trying to help that lady with that damn hat and lost my damn shades?” Because those are the shades that fit me the best, and I still haven’t found nothing better than that.

That made me think of that part of the special where you said you fell in the pool and you never took a swimming lesson.

“I just try to do my best to relate to the stories that I know that’s most common in our life.”

No, I ain’t fall in the pool. Pushed me in pool. I was out that water because I wasn’t even supposed to be over the fence in order to even get pushed. This is the thing. I’m at this factory, and my mom told me not to be at this factory with the other little boys. I fall at the factory. We outside playing. It’s the weekend. This factory is closed. My mother said, “Hey don’t go over there to that factory. For one, you don’t work there, and it’s closed.”

We go over there still. I fall and break my leg. I’m not concerned that my leg is broken. I just need to get to the park. That’s the only thing. I don’t give a damn about this leg, because my leg can be broke, it just can’t be broke here. I got to get to neutral ground. When I tell this story, everybody knows a time that they went somewhere that you got hurt and you like, man, I don’t care nothing about this, I got to get to where I’m supposed to be and then I can deal with my pain once I get there. I don’t know nobody who doesn’t know this story about being somewhere that they don’t supposed to be. I just try to do my best to relate to the stories that I know that’s most common in our life.

Watch more

“Salon Talks” with D. Watkins and comedians