Pinball is of the body: Why modern tech can’t recreate the world under glass

If you pull back the plunger of a pinball machine ever so slowly, your wrist can feel the delicious tension building in each coil of the metal spring, one after the next, as the kinesis of anticipation moves from the machine into your body. And if you pause for the span of a single breath, plunger strained to apogee, and hover at the precipice of launch in that moment-between-moments — your field of vision narrows, your eyes dilate in delight.

And everything else in the room — in the world, in your mind — disappears behind the sharp clack of the plunger’s release.

For many, laying a hand on a pinball machine marked the first time we touched a piece of electronic entertainment tech in public. Once, the frenetic thwacking of flippers was the peak of manic childhood glee. Now, most of us wonder why our little pocket computers — with their nagging buzz of notifications about Candy Crush or Wordle scores — never quite hit the spot. Somehow, after playing with them, you almost feel worse.

Regardless of whether you grew up with pinball, if you’ve ever been stirred to even a passing smile by the sight of a faded old Bally machine flickering alone in the corner of a dim bar, do me one favor. Put four quarters in your wallet. And the next time you spot a pinball machine in a bar, forget about how others may turn their heads at its sound. Forget about how well you play. Just get up, walk over to that clattering carnival in its magic cabinet and pull the plunger.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

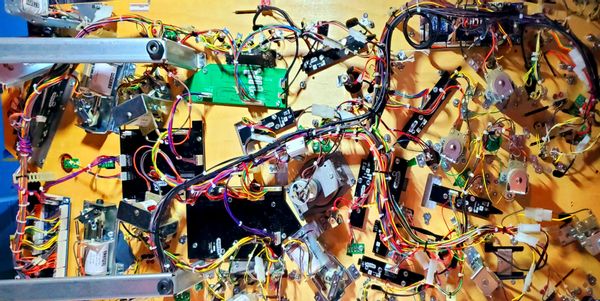

The underside of a pinball playfield reveals the seeming chaos of its careful

The underside of a pinball playfield reveals the seeming chaos of its careful

electrical structure. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

The machinery of physical joy

What most people don’t know about pinball is that the word itself was coined by Kentucky journalists. Louisville newspaper reporters dubbed them pin-and-ball games. Then, during a gambling trial, one of our circuit court judges reportedly used the term to classify the new type of games that had never appeared before in legal literature. Pin-and-ball then quickly became pinball.

After dominating the scores of a weekly pinball tournament in June, Kalyn Smith sits outside Louisville’s most treasured bar-cade, Zanzabar, in the cooling evening.

“I’ll be tired at the end of the night sometimes after a tournament. I’ll go home and sleep well from all the jumping around and shifting, and nudging the machine,” she tells me.

Jeffrey Bilbro once wrote that “the starkest contrast between an industrial economy and a sustainable one lies in the way each deals with death.”

“It’s like mixing a video game with taking a really good hike. You get to the very end of that hike and you feel really good for doing it. But then also, the entire time, it was like a theme park ride where they’re throwing sounds and lights and noises at you.”

The physicality of pinball, like that of all arcade games, is the tech’s blessing on shared social spaces. Its glorious heft unapologetically loud and bright, a cabinet demands due accommodation for spacious human joy and creativity.

As Smith says, it’s a “meshing of physics, bringing it into technology, using it to tell stories and bring them into a physical space.”

A competitive player, builder and part-time technician of pinball machines, Kalyn Smith edges

A competitive player, builder and part-time technician of pinball machines, Kalyn Smith edges

toward 150,000,000 points on Stern’s 2021 “Mandalorian” during a June 15, 2023

tournament. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

The decision of which bodies can occupy those public spaces — and whose stories are told — is never without political dynamic. Pinball parlors have long been dominated by the bodies of men, their stories painted lurid on the back glass of machines in corny, sexualized images of cartoonishly buxom women. Times are changing, though.

“For for a while there, especially when I first started doing tournaments, it was pretty much all older cis males. But luckily it seems like it’s definitely getting more diverse,” Smith says.

In Smith’s state, the current top-ranked player is Elizabeth Gieske, whose sudden rise began with a 2018 tournament win. Smith, however, has been clamoring in front of pinball machines since she was a baby.

“My parents were in bowling leagues so multiple nights a week we’d be at the bowling alley and my parents would bring the crib and put me in there. And basically from the point I was able to stand, they’d push a little chair up to the machine and I’d play it. My dad would kind of stand up behind me to do my hands.”

Pinball’s rich public physicality, though, is its greatest vulnerability. Zack Kamerer is the former owner and CEO of Retrocade, previously in nearby New Albany, Indiana. After six years tending his pinball machines, the COVID pandemic brought an end to Retrocade.

“In 2020, I had to shut my business down during COVID to survive,” Kamerer tells me. He had to sell all his machines.

“It’s exhausting but, yes, I want to get that going again,” he says. “The love for the game has never died.”

Players take to the machines to compete for a cash prize at a local pinball tournament

Players take to the machines to compete for a cash prize at a local pinball tournament

on June 15, 2023. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

Pinball’s latter-year resurgence in popularity has ratcheted entry prices. But the satisfaction of their care is worth it to most.

“Keeping a game, older than you are, running? That’s something special,” Chris DeWitt tells me between rounds.

DeWitt and his son are a regular sight at the arcade. They’re restoring two pinball machines together in their garage, with a new one on its way. A head and a half shorter than his tournament competitors (and still growing into his mustache) DeWitt’s son drums the body of a pinball cabinet with uncanny skill.

“When we first started playing, I would kick his butt in every game,” his dad tells me. “Then he slowly started getting up there, and now he’s way above me.”

A playfield illustration by Kevin O’Connor, from Bally’s 1981 “Medusa” (Photo by Rae Hodge)

A playfield illustration by Kevin O’Connor, from Bally’s 1981 “Medusa” (Photo by Rae Hodge)

A planned obsolescence of the body

Author Jeffrey Bilbro once wrote that “the starkest contrast between an industrial economy and a sustainable one lies in the way each deals with death.”

Bilbro was talking about the writing of Wendell Berry at the time — Kentucky’s beloved farmer-poet, its most famously anti-computer cultural critic and perhaps the greatest living agrarian essayist of the English language. Still, Berry’s conservationism holds as true for the death of electronic tech as it does for lumber harvesting.

In his 1989 journal article “Feminism, the Body, and the Machine,” Berry lambasts the era’s burgeoning tech revolution with jarring prescience:

“This revolution has been successful in putting unheard-of quantities of consumer goods and services within the reach of ordinary people. But the technical means of this popular ‘affluence’ has at the same time made possible the gathering of property and real power of the country into fewer and fewer hands.”

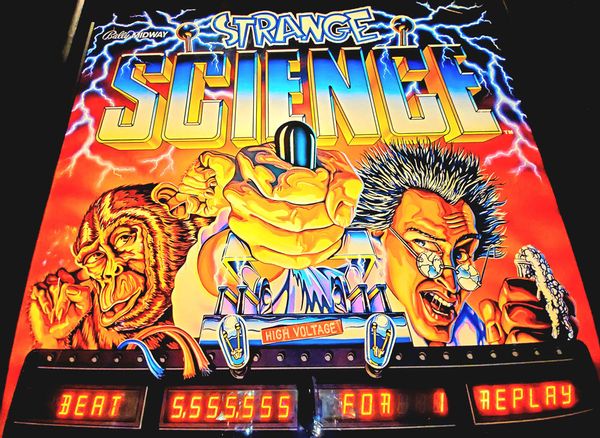

Back glass artwork of Bally Midway’s 1986 pinball machine “Strange Science.”

Back glass artwork of Bally Midway’s 1986 pinball machine “Strange Science.”

Game design by Dan Langlois, art by Greg Freres. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

More than 20 years later, the production of a single iPhone 13 generates 141 pounds of carbon emissions, according to Apple. More than 80 percent of those emissions are created even before transporting the product to the store. While manufacturing millions of iPhones yearly, Apple was hit with a $500 million lawsuit in 2020 over deliberately slowing down its luxury-priced devises as they aged. Apple was accused of the same so-called planned obsolescence in 2022, and again in 2023.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Millennials, meanwhile, play mobile video games at a rate higher than any other generation — yes, even more than Gen Z. Yet the cell phone play-devices are already so inescapable in our working lives that the phrase “social media detox” has become the only polite way to excuse oneself from the repeated physical stress responses the phones deliver. Triggered intentionally by distraction-app peddlers, the physical distress arrives via non-physical triggers on your screen.

The point of which is, of course, to keep you physically immobile, device in hand. Engagement, as it’s called. No need for pinball machines — it’s all on your phone. All the while, the specter of VR threatens to further unwind physical embodiment in both work and creative play.

The playfield of “Strange Science” (Photo by Rae Hodge)

The playfield of “Strange Science” (Photo by Rae Hodge)

“This hatred of the body and of the body’s life in the natural world, always inherent in the technical revolution (and sometimes explicitly and vengefully so), is of concern to an artist,” Berry wrote. “To reduce or shortcut the intimacy of the body’s involvement in the making of a work of art (that is, of any artifice, anything made by art) inevitably risks reducing the work of art and the art itself.”

Berry warns that when companies sell society chintzy techno-frippery disguised as physical or creative convenience, it’s actually human physical craft and creative spirit which that company designs into obsolescence. And he’s mostly right.

The facade of the Pinball Museum of Corbin, Ky. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

The facade of the Pinball Museum of Corbin, Ky. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

The defiant dignity of historical tech-craft

Right-to-repair laws, as they’re called, are hard won victories against the threat of obsolescence (that of both human skill and mechanical quality). They prevent tech giants, like Apple, from withholding critically necessary device schematics from independent repair shops. Microsoft has similarly withheld spare parts from Xbox owners, forcing gamers to navigate an obstacle course of warranty voids.

Ultimately, right-to-repair laws are about nothing so explicitly as creating a sustainable economy of death among machines — an economy that can only exist by hewing to nature’s own cyclical economy of use, repair and the enriching decay of repurposed materials. A purist as far as these things go, Berry would likely say I’m wrong to equate his ecological principles to the cultural conservation of aging media tech.

“A computer destroys the sense of historical succession, just as do other forms of mechanization,” Berry wrote in the same essay. “The well-crafted table or cabinet embodies the memory of (because it embodies respect for) the tree it was made of and the forest in which the tree stood … All good human work remembers its history.”

The thing is, a well-crafted pinball cabinet embodies the memory of, and respect for, its internal computers and tech-craft. Any decent arcade repairman could tell you as much.

A pinball repair technician lifts the playfield of Argosy, the last four-player electromechanical

A pinball repair technician lifts the playfield of Argosy, the last four-player electromechanical

manufactured by Williams, to demonstrate the technical assembly tucked

beneath. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

Though he’s one of the most highly skilled and sought-after pinball technicians in the region, Heath Ashley still humbly calls himself “an eight-year rookie” in the repair world. With a waiting list that runs six to eight weeks long, Ashley works six days a week catering to Louisville’s growing collection of arcade games.

He began tooling with pinball machines as a hobby in 2015 in South Carolina, where he would go on to win the 2016 state pinball championship. By 2019, though, Ashley’s prodigious technical talent became so widely known that he’d run out of machines to fix. He’d effectively repaired himself out of a job.

“On purpose,” he added. “Because there’s so much work. I ran out of work in South Carolina, so I moved here, but I try to do that for everybody. As far as the customer goes, I should only see them once every 5 to 8 years.”

At equal ease with both vintage electromechanical and the latest solid state machines, Ashley’s nuanced knowledge of pinball’s technical history seems at times encyclopedic. Some owners may not find their own broken machines worth repairing, but Ashley said he’s yet to encounter one that can’t be brought back to life.

Among the older Bally machines from the late 1970s, for instance, repair can be fairly easy for a skilled tradesman. Many need only comparatively simple fixes, and the more popular models were produced in large volume in their heyday.

“Electronically speaking, the majority of the parts you can get, but you have to have some skill to install the parts to make it work again. And it’s so much easier to diagnose those games because it’s going to be one of a handful of things,” Ashley said.

Part of Bally’s longevity in that run of machines was also seeded in the economy of their modular design.

“They had the same motherboard communication system with the driver board, and with the lightboard and the soundboard. So they were somewhat interchangeable,” Ashley said.

Renown pinball and arcade technician Heath Ashley explains the nuanced detail of a

Renown pinball and arcade technician Heath Ashley explains the nuanced detail of a

pinball game’s circuitry schematics. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

Smith is a part-time repair technician herself, and is building her own machine.

“We’re encouraged more and more to just throw things out when we’re done with it. And it may not be able to do everything anymore, but there are still roles for everything. I have an old Macintosh from the 80s that I still use like a sequencer,” she said.

Smith sees the planned obsolescence of modern consumer tech — and tech companies’ fight against right-to-repair — as anathema to the legacy of pinball.

“We’re encouraged more and more to just throw things out when we’re done with it. But there are still roles for everything.”

“Most of these pinball machines wouldn’t exist anymore if people weren’t allowed to fix them,” she said.

“You go to some of the sketchy bars where they just don’t take care of their machines. They get a brand new machine in their place. Great. Two weeks later? If people aren’t taking care of these things, they just don’t exist.”

In a pinball machine’s use-and-fix life cycle, the fix isn’t the only thing keeping it alive; the use itself is just as important. Its internal electromagnetic coils, when heated and engaged, are what bring to life the kinetic delights of the flashing playfield.

“You’ve got to keep the coils hot a little,” Smith said. “If they stay too cold for too long, they can kind of get a little more brittle, and not be as strong.”

The game’s own physical lifespan, then, is directly lengthened by the joy it brings you. A pinball machine can only stay alive if you play with it. And if you don’t, it slowly starts to die inside.

Detail of Argosy playfield. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

Detail of Argosy playfield. (Photo by Rae Hodge)

“A lot of people look at a pinball machine and they just see the lights and the bells and sounds. But it’s more, especially since around the early 90s, once they started getting advanced,” Smith said.

She tells me it’s called a “world under glass.”

“The whole game is a metaphor, where the ball is. In each game, the metaphor can be a metaphor for a different thing. Like in ‘Godzilla,’ the ball is a metaphor for Godzilla. You’re going around the city, you’re destroying stuff. In ‘Led Zeppelin,’ the ball represents the band, and you’re going around your tour, playing the shows, playing the songs.”

Maybe it’s true. As you twitch anxiously in the baleful light of a disposable phone, trading away your rich embodiment of joy and toil for the oily promise of more time saved, which you use only to stare blankly in dissociative haze, maybe you’re the obsolete technology.

But there is no doubt — in the world under glass, when the urgent plunger springs to life from your sweaty grasp and you hammer fingers down on the flipper buttons with ecstatic abandon — the pinball is you.

Read more

about tech culture