Shooting hoops and K-dramas: The American dream of not being relegated to a subplot

“It just felt like magic. I was telling my wife at the time, ‘I’ve never felt so good about this country.’ It really still is the moment I felt the best about the political climate.”

No, author Matthew Salesses isn’t speaking about the election of Barack Obama as president, but rather an event that occurred in the middle of his two terms: Linsanity.

In the 2011-2012 season, point guard Jeremy Lin led the Knicks in a turnaround with a seven-game winning streak that became a cultural phenomenon known as Linsanity. For a while it seemed that goodwill for Lin united the nation. He wasn’t just recognized as this savior of the team, but also significantly as an Asian American man rising in a sport that had never seen the likes of him before. And then the streak ended, and eventually, the Knicks let Lin go.

“For those two weeks it felt so supportive and amazing. It felt like everybody was rooting for him, for this possibility to open up,” Salesses told Salon in a Zoom interview. “When that all fell apart, it was very disappointing. It felt really like a referendum, like a door closing right in our faces. Afterwards, it was clear people were holding back their criticism.”

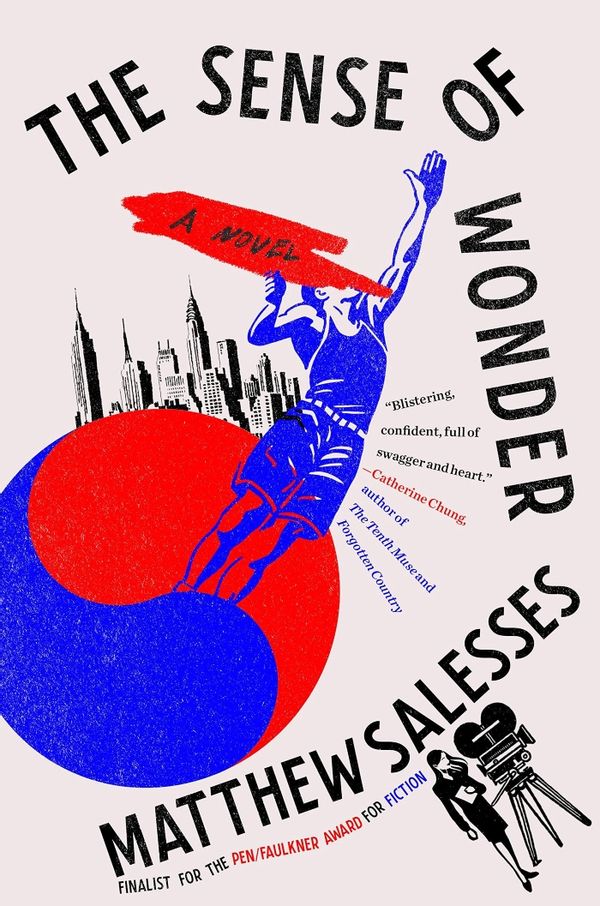

In the author’s new novel “The Sense of Wonder,” fourth-string point guard Won Lee gets off the bench to lead the Knicks in a similar winning streak that the media dubs the Wonder. As star teammate and captain Paul Burton – better known as Powerball! – continues to be sidelined with an injury, all eyes turn to Won as the Knicks’ only hope to make it to the playoffs.

The story for “The Sense of Wonder” came naturally to Salesses, who grew up dreaming of being in the NBA, but often felt limited in that dreaming as an Asian American.

“My friends and I, who all wanted to be NBA basketball players, we were always talking about who our game was like,” he said. “We had these kind of stars in mind, and it was always pretty hard for me to figure out who that was. The idea that somebody Asian American could make it in the league was really not something I was used to being told all the time and seeing all the time. And so [with Linsanity] it really felt that somebody was giving us a chance.”

It’s clear that even before Salesses became a storyteller, he felt subject to the power of the prevailing narrative – or lack of one – about Asian Americans playing basketball. In “The Sense of Wonder,” Won only gets his chance when Powerball! throws out his back. And reporter and fellow Korean American Robert Sung only covers the Knicks after losing his chance at achieving his own hoop dreams. (“In the story of his life, he was a subplot,” Salesses writes.)

The narrative of Asian Americans excelling in anything other than the expected sports – figure skating, martial arts, gymnastics, table tennis, etc. – is still framed as an oddity. In the new Disney+ movie “Chang Can Dunk,” sophomore Xiao Ming “Bernard” Chang (Bloom Li) worships Kobe Bryant’s work ethic and goes into rigorous training to prove in front of his entire high school that he has the ability to slam dunk.

“If I could dunk it would be proof that I could be more than who I am,” says Chang. For him and Won Lee, playing basketball is more than just access. It’s about being seen, about not being relegated to a subplot, even in one’s own mind.

The importance of centering narrative continues when “The Sense of Wonder” moves from sports to another facet of the Korean American pop culture identity. Won Lee’s girlfriend Carrie Kang is a producer of Korean dramas overseas, but her dream is to create a K-drama in America. “To be a minority in America is to guard what you love from other people’s scorn,” she observes.

As a Korean adoptee, Salesses didn’t grow up with K-dramas and only started watching them as an adult after visiting Korea and meeting his first wife. When she was diagnosed with Stage 4 stomach cancer, they turned to these shows for comfort. Today, Salesses equates the optimism – that sense of wonder – evoked from Linsanity with the feelings he gets watching K-dramas.

“I love where it’s gone now,” said Salesses about how K-dramas have become increasingly embraced, “but I think people are watching the wrong dramas.”

Check out the rest of my interview with Matthew Salesses for more about basketball, storytelling, puns and his favorite K-dramas.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Paint me a picture – just how devoted were you when it came Linsanity? Were you already a Jeremy Lin fan? Did you follow the Knicks?

I am not a Knicks fan. I actually just moved to New York. I grew up in Connecticut, but in the Boston side of Connecticut, so I grew up a Celtics fan. But I had been following Lin since his time in Harvard loosely and then a little bit more once he had that NCAA tournament breakout game. I had been watching his performance over the summer league. He had this big game against John Wall, the No. 1 pick in the draft, and then still wasn’t picked up. He had to go and get an un-guaranteed contract.

So when Linsanity happened, I already knew who he was. I had been hoping for a couple years that he would get a chance. But of course, I hadn’t expected what happened. It felt unreal or like a heightened reality. I was following it really closely, watching every game, watching all the news coverage, every single thing I could get my hands on. I’ve never felt so good about this country . . . and it’s just about basketball. Like, how ridiculous, you know?

Do you own any merch?

I have a Lin jersey.

You make Won Lee the Korean American version of Jeremy Lin in your book. There’s a famous headline regarding Lin that involves a racial slur. Since the media’s coverage of Won plays a big part in this book, did you want to mimic that with the Great Wall [of China] headline?

“When you aren’t allowed in a certain space, and then somebody just lets one of you in, they’re like, ‘You should be so grateful for being here at all.'”

Yeah, I used the Great Wall thing. I didn’t want to recreate the slur; we didn’t have to be re-traumatized by it. But I remember at the time [reading that headline] thinking maybe it was a mistake. It’s a common phrase. And maybe the editor will come out and apologize. Like, “I’m so sorry, I totally didn’t mean this.” But instead, he said, “Oh, I’ve never even heard this term before.” And that was like, “There’s no way you haven’t heard this before. So now you’re just telling on yourself.” It was disappointing.

Jeremy Lin #17 of the New York Knicks drives for a shot attempt in the first quarter against the Los Angeles Lakers at Madison Square Garden on February 10, 2012 in New York City (Chris Chambers/Getty Images)As with Jeremy Lin, Won Lee experiences backlash after the Wonder ends. There’s resentment, and he’s expected to take a backseat again. One line in particular resonated with me: “He had broken the rules of gratitude as an Asian.” Could you discuss that sentiment?

Jeremy Lin #17 of the New York Knicks drives for a shot attempt in the first quarter against the Los Angeles Lakers at Madison Square Garden on February 10, 2012 in New York City (Chris Chambers/Getty Images)As with Jeremy Lin, Won Lee experiences backlash after the Wonder ends. There’s resentment, and he’s expected to take a backseat again. One line in particular resonated with me: “He had broken the rules of gratitude as an Asian.” Could you discuss that sentiment?

The gratitude thing comes straight out of adoption for me. When I was growing up, everybody was always saying to me, “You must be so grateful. Your parents saved your life.” And every time somebody said that, it made me less grateful. It felt like gratitude then became a kind of weird weight around my neck and something I didn’t want to be grateful for. And that too, felt bad, right? So it’s this cycle of guilt and gratitude.

And I do think sometimes when you aren’t allowed in a certain space, and then somebody just lets one of you in, they’re like, “You should be so grateful for being here at all.” But you’re like, “I’m not really even there,” or “You haven’t even really let me in, and yet you’re asking me to be grateful.”

How much did you want Won Lee to mirror Jeremy Lin’s career trajectory?

At the time when I was really working on the book, Lin was still in the NBA. So he hadn’t gone to China yet to play there. And Won has the option to go to Houston, gets the same kind of contract, but instead goes to Korea. At first, I was going to have him follow the same trajectory: go to Houston and be shuffled around the NBA.

But I wanted to have a K-drama happy ending. And I still think, looking around, it doesn’t seem that’s possible here. And so where’s the place he would be accepted and have a real chance at playing in a way that would just be about that joy of playing basketball? For me, that seemed like the choice was to go to Korea, a place where people can see you as whatever you want to be. It was funny because Lin’s decision to go to China was after I’d made the decision to send Won to Korea; I thought maybe maybe he had the same feeling.

The character of Robert Sung is intriguing in that he’s also a Korean American who showed promise with basketball but suffered a career-ending injury. Now he’s a reporter who exclusively covers the Knicks and his former teammate Powerball! You’d think he’d be supportive of Won, but they’re almost like frenemies instead.

I was writing this story about this basketball player who has the skills and should be an insider in that game and on his team, yet he’s treated all the time like an outsider even when he becomes a star. I had Sung as this kind of foil to Won. For me, it was the second layer of being an outsider within a community. So Sung is adopted and he’s in this Asian American community and has all of these things in common with Won, but in the end, he’s still always kind of treated as somebody outside of things, at least by Won.

It’s probably not the same for everybody. I’ve often felt I’ve gained so much from the [Asian American] community, I’ve found so much love within the community and yet also there are times when it seems people are like, “You don’t belong. You’re not like a real Asian.” So I wanted to kind of get that in the book as like this extra layer of the same kind of phenomenon.

Robert Sung’s trajectory as a Korean adoptee is different from your own. What did you want to explore with him?

“I’ve found so much love within the [Asian American] community and yet also there are times when it seems people are like, ‘You don’t belong. You’re not like a real Asian.'”

I’ve written within Korean adoptee characters before as a Korean adoptee. But I wanted to see what it would be like to think about how people sometimes see us, from within the Asian American community. And since I had Won as the narrator, I wanted to see what he would think about Robert Sung. I give Sung some loose details of my own life: adoption and Catholicism. But really, most of it is pretty divergent.

The thing that really interests me about Lin’s story is we don’t know what it’s like on the inside. I’ve watched the docs and stuff, but I imagine it’s probably much harder and much more complex from inside that story. But all we see is this stuff from outside. And that’s the stuff that I was interested in, putting that pressure on Won. And then also having Won be a narrator and putting that pressure on somebody else. So we never really get Sung’s story the way that he would tell it; that was something I wanted to play with here. But then I wanted to throw other adoptees in the bunch just so that we don’t think this is the adoptee experience, because I don’t think that it is.

Your previous novel “Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear” gets a fun callback because it’s the title of a chapter in “The Sense of Wonder.” How does disappearance relate to Won?

We’re disappeared a lot, right? I think “Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear” is obsessed with: What does it mean to appear? And what does it mean to disappear? And if we’re going to be disappeared, is there a way to make that positive and not a terrible experience since it’s just a basic fact of life as a racialized minority?

So, the story of Won’s rise is a similar story. He’s appearing in a way; he’s all over the news. But it’s not really him. So it’s another kind of disappearance too. I just wanted to kind of acknowledge that but also put it in for fan service or as Easter eggs.

Did the name Won Lee come first or after the idea for his basketball winning streak known as “the Wonder”?

What came first was Won Lee’s name. I just thought it would be funny for a basketball player to have the name, like you win a game. Lots of things start as jokes for me in my head that will just be funny for me as I’m writing.

Powerball! with an exclamation point. I thought, “How fun would it be to change your name to something where every time a reporter had to write about you, they would have to write an exclamation point?” There’s this writing rule, people say you only get three exclamation points in your life. So that was like a way to force multiple exclamation points into the book.

“The Sense of Wonder” by Matthew Salesses (Little, Brown)Switching to K-dramas now – you develop a pretty detailed plot for the series that Won’s girlfriend Carrie Kang is shooting in Korea. It’s a romantic comedy between a man who can predict the future (thanks to a ghost) and a woman who can see ghosts. As an American writer, did you find it more challenging to create a K-drama story?

“The Sense of Wonder” by Matthew Salesses (Little, Brown)Switching to K-dramas now – you develop a pretty detailed plot for the series that Won’s girlfriend Carrie Kang is shooting in Korea. It’s a romantic comedy between a man who can predict the future (thanks to a ghost) and a woman who can see ghosts. As an American writer, did you find it more challenging to create a K-drama story?

I have these show ideas from a while back. One day, I want to write these shows. But of course, I can’t really speak Korean well enough to write a show in Korean. And I have no connections to the K-drama industry. So it seemed like a chance to get these things that I thought would be fun to write onto the page. Then as I was writing “For the Love of Your Future Self” –

Which is a fantastic title, by the way.

Thank you, it’s a really K-drama title. It’s very cheesy, but also punny.

So I was writing that and at a certain point, I thought I could just write the entire thing here. But actually, then it will seem like a singular show. And what I wanted to show was how they’re following certain marks and have certain kind of tropes that happen across different shows. That’s why I decided to have a different show for the second half of the K-drama [part of the book].

What sort of research did you do for the development and production side of K-dramas?

“In K-dramas it’s kind of interesting in that almost all the all the writers are women, but almost all the directors are male.”

There’s this great drama [“Worlds Within”], it’s older with Hyun Bin and Song Hye-kyo. They are [playing] producers of K-drama. So there’s a few shows where you can see the characters are working on K-dramas. Those helped a little bit. There are certain variety shows, too. You can see they interact more with the staff. And sometimes you’ll see like the staff get involved in the show, to see more of the behind-the-scenes too.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

You had to write from the point of view of a woman with Carrie’s chapters. So you also dig into her experiences of gender discrimination in production. What did you want to explore there?

It seems like from knowing people, there’s so much of that discrimination. And even the show with Song Hye-kyo deals with some of that as a woman in a male-dominated field. In K-dramas it’s kind of interesting in that almost all the all the writers are women, but almost all the directors are male. So I think that dynamic is pretty interesting.

Carrie is coming into the drama from the production side that’s very male, as a woman, but also as an American woman, as somebody’s completely outside of the country. And yet, you know, she’s Korean American, so she can speak Korean. And she has some understanding of what is going on there. Of course, she has her whole professional career, so it’s not like she has no experience.

A lot of the voice was thinking about how the various ways in which, like, I think sometimes for me voice is about like, the resistances that we come up against. And the ways in which we have learned to speak at or around those resistances. And so, for Won, there are very different kinds of places where society chafes against what he wants to say.

Lee Byung-hun as Eugene Choi and Kim Tae-ri as Go Ae-shin in “Mr. Sunshine,” a historical K-drama involving four nations, spies, revenge and romance (Netflix)While a lot of the world watches K-dramas, for some, they’ve only heard of “Squid Game” or maybe hear they’re romantic, but nothing more than that. I read that your first wife had introduced you to K-dramas. What was your awareness of them before that?

Lee Byung-hun as Eugene Choi and Kim Tae-ri as Go Ae-shin in “Mr. Sunshine,” a historical K-drama involving four nations, spies, revenge and romance (Netflix)While a lot of the world watches K-dramas, for some, they’ve only heard of “Squid Game” or maybe hear they’re romantic, but nothing more than that. I read that your first wife had introduced you to K-dramas. What was your awareness of them before that?

I had no awareness really of anything Korean growing up . . . When I went to Korea I was 23 and still had no idea about anything. I was afraid to eat the food because I had read this “Lonely Planet” guide on the plane over, and it was like, You could get diarrhea. I was going out and I don’t even know what this food is because I’ve never seen it before.

I met my wife pretty early on and actually would have left Korea and never gone back probably if I hadn’t met her. So in the process of teaching me how to eat . . . we also were watching Korean movies. Korea has all these rooms where you could go and do small-scale versions of the big thing. So we would go into a DVD bang and watch a movie in that private movie theater or watch dramas online.

I think the first one I watched was “You’re Beautiful,” which is one of the Hong sisters dramas. It’s Park Shin-hye in kind of her breakout role because she was a child actress before. There’s this popular boy band, and her twin brother is joining this boy band. And they’re identical twins, but he has gone to America to get some kind of plastic surgery, and the surgery has gone wrong. So he can’t join right away, but it’s a huge break for his career.

“K-dramas are very comforting to me. I need a lot of comfort.”

She’s trying to become a nun. [Laughs] And his manager comes and gets her and is like, “You have to do this for your brother.” So she steps into his role and pretends to be him and joins this boy band group. Of course, all the boys fall in love with her. Some of them know that she is a woman pretty early on, and some of them don’t. So it’s just a funny, “Who are we in love with?” thing. It’s pretty good.

I kind of wanted to hate it because it’s so cheesy, and I was a much younger man at the time and wasn’t comfortable being sentimental. But it was so compelling. It just kind of pulls you right through it. You have no time to hate it. K-dramas are very comforting to me. I need a lot of comfort.

Many K-dramas involve body swapping, souls of people taking over other bodies or like in Carrie’s show, a ghost attaching itself to people. Could you talk a bit a little bit about the K-drama concept where there is this thin line between supernatural and reality as we see it?

It’s about accepting the idea that the supernatural is all around us. That the things in Korean fairy tales or superstitions are actually just one half-step away from where we are already.

If you are in Korea, you see people accepting the fact that ghosts are real. It’s only a little bit farther to go from that to somebody can talk to ghosts. And they can do weird things in life, like a virgin ghost inhabiting the body of a woman who doesn’t like this guy [as in “Oh My Ghost.”] So you’re taking this already existent feeling that the supernatural exists, and just making it a little bit more tangible.

Then adding to that, my book talks about this a lot, there’s this different way of thinking about the world and what happens to us in the world [as Americans]. Whereas Korea is a country obsessed with birth. It’s like, you are who you are because you’re born that way. You’re Korean, because you’re born Korean; it’s so much blood, and you’re so much genetics. To me, if you start thinking critically about the cultural socioeconomic factors that make us who we are, all that stuff is pretty much determined at birth too, right? If you think what’s the number one determiner of your income level – it’s your parents’ income level, right? So those things all come together in K-drama.

Sometimes those are criticized. Dramas are making critiques like “Squid Game” about the ways in which you’re fated at birth, what is possible for you in life. And sometimes, it’s more like star-crossed lovers who might have were born once 1,000 years ago, and came to a bad end, and now they’ve been reborn and are trying to make it work this time.

So, yeah, it’s definitely a different way of thinking about the world. But I think I entered that world right away because it felt so real in a sense, of – what’s the driving factor behind a life? It seems like that to me is not so much like we get to make all these choices, and those things determine what happens to us. My life hasn’t been like that much. [Laughs]

Yeom Hye-ran as Kang Hyeon-nam and Song Hye-kyo as Moon Dong-eun in “The Glory” (Graphyoda/Netflix)You mention with Carrie’s character, when she gets angry she says, “I wanted to revenge all over the place.” Revenge is one of the themes I’ve noticed with a lot of K-dramas like “The Glory,” which also stars Song Hye-kyo. What are your observations about Korean revenge TV and movies?

Yeom Hye-ran as Kang Hyeon-nam and Song Hye-kyo as Moon Dong-eun in “The Glory” (Graphyoda/Netflix)You mention with Carrie’s character, when she gets angry she says, “I wanted to revenge all over the place.” Revenge is one of the themes I’ve noticed with a lot of K-dramas like “The Glory,” which also stars Song Hye-kyo. What are your observations about Korean revenge TV and movies?

I love it. I love it so much. “City Hunter.” Have you seen that one? It’s so good. I love all the Korean revenge dramas like all the Park Chan-wook series, that trilogy [“Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance,” “Oldboy” and “Lady Vengeance.”] I think it’s this Han thing, this desire for revenge. And I’m actually writing right now a revenge story novel, which is basically a K-drama – let’s be real. [Laughs]

Intriguing. What can you say about that story?

It’s about an Asian American revenge cult. So from the time the first official Korean Americans appeared in America, they’ve been taking revenge on people. And it’s a younger girl, 12 at the beginning of the book. She’s being bullied a lot in school; it’s my first time trying to set something in the area that I grew up in. And she finds out that her parents are part of this revenge cult, so she’s inspired to take revenge.

Read more

about this topic