Watchdog warns monitoring not keeping up with surveillance tech

Monitoring of high-tech surveillance systems is not keeping up with technology, a watchdog has told BBC News.

Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner Prof Fraser Sampson also warned of an urgent need to wake up to an “explosion” of devices such as dashcams, drones and body-worn video.

Planned legal changes would remove a key code and oversight, he said.

BBC News has asked the Home Office and the police for comment.

Oversight gaps

Prof Sampson was announcing the publication of his latest and probably last annual report.

If the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill becomes law, Prof Sampson’s role will cease, shifting some of his responsibilities to other regulators.

It would also end the Surveillance Camera Code, which governs police and local authorities in England and Wales, he warned.

“It simply abolishes what we already have,” Prof Sampson told BBC News.

“In which case, those rules that we currently have will be gone and then there is no clear indication of what might replace them and who might be responsible for overseeing that.”

There are already gaps in oversight and a need for greater regulation in some areas, Prof Sampson suggests.

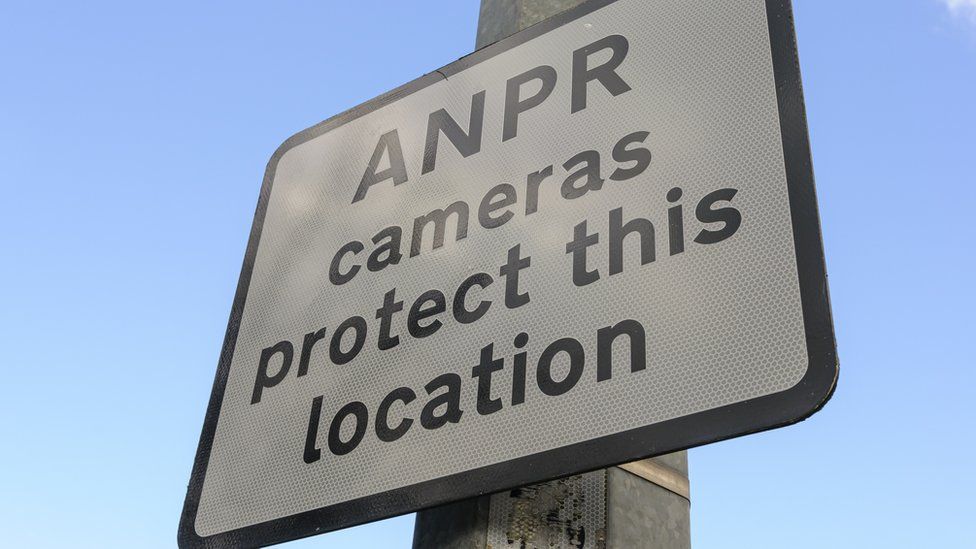

His report highlights the use of automatic number-plate recognition (ANPR) cameras and concerns about “mission creep”.

Used by police to track vehicle movements, ANPR is also used to enforce low-emission zones and check cars have insurance.

It is “the largest non-military database in the UK”, Prof Sampson writes, “15,400 traffic lanes covered by cameras submitting between 70 and 80 million reads a day” – a critical system, the loss of which would have “unimaginable” consequences for policing.

But he told BBC News: “It has no specific legal underpinning.

“There is no ANPR legislation or act, if you like. And similarly, there is no governance body to whom you can go to ask proper questions about the extent and its proliferation, about whether it should ever be expanded to include capture of other information such as telephone data being emitted by a vehicle or how it’s going to deal with the arrival of automated autonomous vehicles.”

And when it came to independent oversight and accountability, “I’m the closest thing it’s got – and that’s nothing like enough”.

‘Sinister development’

Prof Sampson also said regulation was falling behind advances in biometric surveillance – live face-recognition cameras that can match passers-by to a police watchlist or artificial-intelligence (AI) systems that can rapidly search footage for individuals.

He also has reservations, in all but exceptional cases, about the potential use by police of facial-recognition technology to retrospectively identify witnesses to crime.

Tracking people an algorithm says were present at an event, identifying them against a national database of images and “inviting” them to disclose what they heard and saw would be “a new and somewhat sinister development”, Prof Sampson writes.

And at the end of a 30-minute phone interview, he told BBC News AI’s ability to scan the mass of biometric data from cameras and other sources “is increasing not only every day – it’s increased since we began this interview”.

Drones capturing footage of public spaces as they operate, such as from a planned 164-mile “drone highway” for commercial and medical deliveries, also posed new questions for regulators, Prof Sampson said.

He also said the police would often now, as a first response to a significant incident, ask for any images or footage the public may have captured themselves on their own devices.

“Increasingly, the state needs images from the citizen,” Prof Sampson said, and that too opened up new areas in need of regulation.

Related Topics

-

-

29 June 2022

-

-

-

4 July 2022

-