Their children struggled with addiction. Now, they’re fighting against the war on drugs

Over one million Americans have died of drug overdoses since 1999, with around 110,000 deaths alone in the 12-month period ending in May 2022. Every single person that overdosed had parents. They were someone’s child at some point.

Often, when a parent loses a child to an overdose, they might be seen holding a press conference with the police, calling for stronger punishments for those that possess or use drugs like fentanyl, a synthetic opioid driving overdose deaths. That response is understandable: the culprit most apparent in these kinds of deaths is the drug itself.

Yet there are some parents who are organizing together against this narrative — parents whose children have struggled with addiction, and even passed away in some cases.

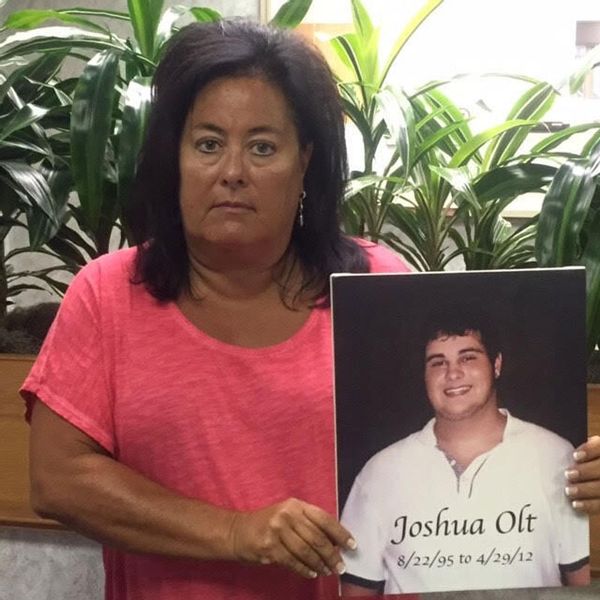

Salon spoke with Gretchen Burns Bergman, whose two grown sons who are in long-term recovery from heroin addiction, and Tamara Olt, M.D., who lost her 16-year-old son Joshua to an accidental heroin overdose in 2012. Both strongly advocate for a more rational approach to how we treat substance use in the U.S.

“To throw money at going after the supply side and building up criminal justice, it’s appalling. It didn’t work, it hasn’t worked. Drugs are still there,” Bergman told Salon. “People are still dying. We need a compassionate, tolerant, science-based approach to this issue.”

Bergman is the executive director and co-founder of A New PATH (Parents for Addiction Treatment and Healing), a non-profit organization that works to reduce the stigma associated with substance use disorders through education and compassionate support, advocating for therapeutic rather than punitive drug policies. Olt is a board-certified obstetrician-gynecologist who, with her husband Blake, started Jolt Foundation, which focuses on awareness and prevention in the overdose crisis. and overdose prevention. Olt is also the executive director of GRASP (Grief Recovery After Substance Passing) and Broken No More.

Their stance on drugs and drug use is very much rooted in fact. The United States has tried prohibition for approximately a century and yet problems like addiction and overdose are increasing, not decreasing.

Meanwhile, trillions of dollars have been spent on supply side interventions like increased surveillance, prisons and dumping pesticides on the Colombian rainforest. Yet, there has been little to show for these efforts, while public health agencies, including experts at the United Nations, repeatedly advocate for smarter, more compassionate drug policy rooted in science.

Bergman, Olt and other parents recognize this and have taken a stand, advocating for harm reduction or decriminalization instead of incarceration or criminal records, giving people tools to stay alive rather than shaming them for illicit drug use.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Can you tell us a little bit about how your advocacy work began?

Gretchen Bergman: 23 years ago, I co-founded A New PATH with two other parents. We all had children who were struggling with substance use disorders, compounded by a criminal justice system that misunderstood and mistreated the problem.

My older son was 20 when he was arrested for marijuana possession, which started 11 years of cycling in and out of prison for relapse, but all for drug-related, nonviolent offenses, which was a tremendous waste of human potential and a real trauma for the family. My second son had the same disorder and struggled for 20 years, but the criminal justice system always made things worse, always created roadblocks.

So I started A New PATH because I wanted to change powerlessness into empowerment. I felt like it was basically lack of the understanding of the basic nature of substance use disorders that we’d allowed the criminal justice system to take it over rather than it being handled as a public health problem.

Tamara Olt (Photo courtesy of Tamara Olt)

Tamara Olt (Photo courtesy of Tamara Olt)

Tamara Olt: In 2012, when my son Joshua died at the age of 16 from a heroin overdose, we didn’t know he was using drugs. We never got a chance to try and get him help. He didn’t reach out to us, I think because of shame and stigma. And he used for probably only six months before he overdosed and died on the way to the hospital in the ambulance.

It was a complete shock to us. All of a sudden, my world was just up-ended. I didn’t really know how I was going to get through it. But I decided I could sit in a corner and cry for the rest of my life, or I could get up, tell Josh’s story and try and make a difference, try and make sure no other family had to go through what we went through.

At that point, I didn’t even know what harm reduction was. But as a physician and a scientist, it made perfect sense to me. Of course we’d want to try and reduce harm. Of course we’d want to keep people healthy through their drug use and not use the criminal justice system to take care of them. But let’s use public health and science to help people get through, whether they want to continue using drugs, whether they want help, wherever they’re at.

The Jolt Foundation began just trying to blanket our community with naloxone [a drug that reverses an opioid overdose.] I also joined GRASP, a peer-led group for people that have lost someone to substance use. GRASP saved my life. I learned from other moms that tried tough love, some people tried supporting their person. But we all ended up in the same place: our loved ones were gone.

We weren’t at home at the time when Josh died. But I also met moms who were laying in that room next to their person when they overdosed. It gave me strength, knowing there were so many other people out there, and where I could share my story, hear other people’s paths to ending up with someone gone from substance use. As I learned more about the drug war, and what an abject failure it has been, I wanted to fight against that, fight for humane, sane, science-based policies that will save lives.

A lot of people have lost their children to overdose, yet it’s sort of counterintuitive for mothers like yourself to stand up and say it’s the system that caused this harm, not the substance itself. But what did it take to change your mind?

Tamara Olt: In the beginning, I was angry, I was grief stricken. I wanted someone to pay. I wanted whoever sold the drugs to my child to be found and prosecuted. Part of the healing process is to forgive. Forgive yourself, forgive your person, forgive anyone who was involved in the death for whatever reason. Until you forgive, you can’t ever really begin to heal. And it really helped. And it led me be able to stand back, look at the big picture. We have a system set up for people to fail, for them to become incarcerated, for them to overdose.

Gretchen Bergman: It does take courage. But that’s the second part of the Serenity Prayer: courage to change the things that you can. And when I started speaking out, you could hear an audible sigh of relief. Other people were experiencing this, but it was so shame-based to talk about it, not only having a substance use disorder, but having being incarcerated.

“I would find needles in the room and I’d throw them away — a far cry to where now I’m handing them out!”

I loved being a mother to two sons. And when that turns out that they both then ended up having a pretty severe case of this disorder, I learned everything I could about it. I thought if somebody had said your son is a diabetic, I’d learn everything I possibly could. Speaking out did take some strength and I still feel the stigma. But I have nothing to be ashamed of. I have two beautiful, strong resilient sons.

Stigma is the number one thing that we’ve worked on from the very beginning. People that are not educated about addictive illness or substance use disorders fall prey to scare tactics from those that would like to bring this issue back into criminal justice, rather than expanding what we really need. We really need more resources. Not just treatment, but prevention and recovery and support services. We’re dismally low on what we need in order to handle this public health crisis.

To throw money at going after the supply side and building up criminal justice, it’s appalling. It didn’t work, it hasn’t worked. Drugs are still there. People are still dying. We need a compassionate, tolerant, science-based approach to this issue.

One of the dominant misconceptions about dealing with a child with a substance use disorder is this idea of “tough love,” even though there is a lot of evidence this can backfire. How do you address that?

Gretchen Bergman: We’ve been working on a “True Love, Not Tough Love” campaign for several years now. I tried tough love, I tried a lot of things. I would find needles in the room and I’d throw them away — a far cry to where now I’m handing them out!

The campaign was meant to debunk the whole concept of codependency, which is not based on fact or science. It was an easy answer from health care providers who say, “You just have to let them hit bottom.” Don’t “enable” them. Basically kick them to the curb.

I know one mother that put her kid out in the tent. He was only 16-years-old. I mean, for God’s sake, that was not the answer. I felt intuitively that it wasn’t. I loved nurturing my children and how dare you take that right to nurture and protect my children away, calling me an enabler and codependent.

I know that my kids have a disorder that will potentially kill them. But that danger is real. I was constantly trying to usher them into resources that would help them and telling them always, you are surrounded by true love. Your family loves you. If we can’t help you find your way out of this maze, we are there. So that they don’t get that sense of hopelessness, “Oh, I might as well keep using, I don’t have a life left. My family doesn’t care, nobody cares, whatever.” I didn’t want them to ever feel that.

And so this campaign addresses that, it allows mothers to listen to their maternal instincts, rather than listening to those who will tell you to turn your back. I knew that the bottom for my kids would be death. I knew it. So I wasn’t willing to go there.

“Both of my sons found different routes to recovery. My younger son had tried everything, but in the end, he went abstinence only. The other son, he found his way to recovery with methadone.”

Tamara Olt: We see people on GRASP that went along with those [tough love] recommendations and their person died and they feel terrible. Like oh, we threw my son out. He died homeless on the streets. Cold, unloved, alone. And then they have to live with that. Even though they did what professionals told them.

Things will happen no matter what we do. Like I said, kids who are never thrown out die in the room next to their parents. But you know, if you lose your person, you want to feel like you did your best and have some peace with that. And not unhoused on the street dying alone with no one there.

It’s a terrible journey and it will never be over. Grief changes, the pain changes, it becomes more bearable, but it’s always there.

What about the stigma against medication-assisted treatment? Tamara, I know you’re a buprenorphine provider. But there is this attitude that abstinence is the only way and that certain medications like buprenorphine or methadone are trading one addiction for another. And this is just so patently false. A lot of people hear this idea, though and they’re afraid to get treatment. And then something happens with fentanyl or something worse. How do you address this stigma?

Tamara Olt: It comes from several different areas, including family members who discourage their loved ones from getting on it. They say you’re just trading one addiction for another. You don’t need that medicine.

I’ve had patients that have to hide it from their family, that they’re in recovery and coming to get buprenorphine so that they don’t use and die. But we know abstinence-based treatment for opioid use disorder has a [high] failure rate. And with fentanyl in the equation, now it can be a death sentence. And then from society in general, from even the medical profession that doesn’t understand it, and doesn’t encourage it. We know it reduces mortality by 50 percent when people are on medications for opioid use disorder. So the benefits and the science is clear.

There’s also a lot of misunderstanding from even people who supposedly are buprenorphine providers that well it’s just for detox. They’re just going to use it for a little bit. Well, no, you can be on this medication for as long as you need to. I tell my patients, if you’ve got to be on this for the rest of your life, who cares? I gotta take my diabetic medication for the rest of my life. It’s not the end of the world.

Gretchen Bergman: There’s stigma also in the recovery community, those that believe in abstinence-based [treatment]. And we’ve been working for quite a while trying to bring the harm reduction world and the abstinence based only world together. Abstinence is one of the tools of harm reduction, like decriminalization is a tool of harm reduction.

Both of my sons found different routes to recovery. My younger son had tried everything, but in the end, he went abstinence only. And I would say it’s because of the embrace of the recovery community. He surrounded himself with people in recovery, who did fun things together: surfing and biking and that kind of thing. The other son, he found his way to recovery with methadone and it allowed him to go back to school and get his degree.

So in our family, we absolutely believe in the many pathways to recovery. I don’t care what it is that you do to stay alive and thrive. If it works for you, then that’s fine. But unfortunately, there is so much stigma associated and ignorance about it.

Read more

about drugs and addiction