Take a deep dive into Abbey Road’s storied legacy as “the world’s most famous recording studio”

The first time I stepped into Abbey Road’s fabled Studio 2, I couldn’t breathe. The very thought that I was standing in the room where the Beatles recorded the vast majority of their unparalleled music was simply overwhelming. With “Abbey Road: The Inside Story of the World’s Most Famous Recording Studio” (currently in UK release), David Hepworth affords readers a stirring history of the much-heralded studio and the magic that has transpired within its hallowed walls.

An esteemed music critic and journalist, Hepworth provides us with a deep dive into the story behind the 91-year-old facility, a stirring narrative that mirrors pop music’s twists and turns from its earliest days through the present. Purchased by the Gramophone Company in 1929 for £16,500 and rechristened as EMI Recording Studios, the facility officially opened in November 1931—scant months after Columbia Graphophone had merged with the Gramophone Company and formed the EMI Group.

As Hepworth points out, the studio was making history in nearly the same instant in which the facility first opened its doors. In the early 1930s, English composer Edward Elgar conducted the historic recording sessions at EMI Studios for “Pomp and Circumstance,” the series of five marches that would immortalize his name — the march entitled “The Land of Hope and Glory” emerged as a British sporting anthem, while “The Light of Life” became the signature melody for American graduation ceremonies.

During EMI Studios’ early years, the facility developed a reputation for classical recordings from the likes of Yehudi Menuhin and Pablo Casals. In keeping with EMI’s air of formality and British aplomb, studio personnel sported white laboratory coats. In 1940, Winston Churchill visited EMI Studios to make propaganda recordings for the war effort. Seeing the white-coated engineers milling about the studios, the Prime Minister famously quipped that there were so many white coats in evidence that he thought he’d “ended up in a hospital.”

As Hepworth powerfully demonstrates, Abbey Road created the firmament for recording artistry, a genre in which the very idea of the studio is upended. Formerly a means for reproducing an artist’s repertoire, the recording studio was eclipsed by larger, more lasting notions of art and the production and reproduction of sounds originally borne by the creative imagination. “With the new ability to control the inputs, recording music successfully involved something more than fidelity to the original performance,” Hepworth writes. “It suggested that the record could even offer, in certain cases, something better than live music, something more mysterious, more narcotic, something which, over repeated listens, got under the listener’s skin.”

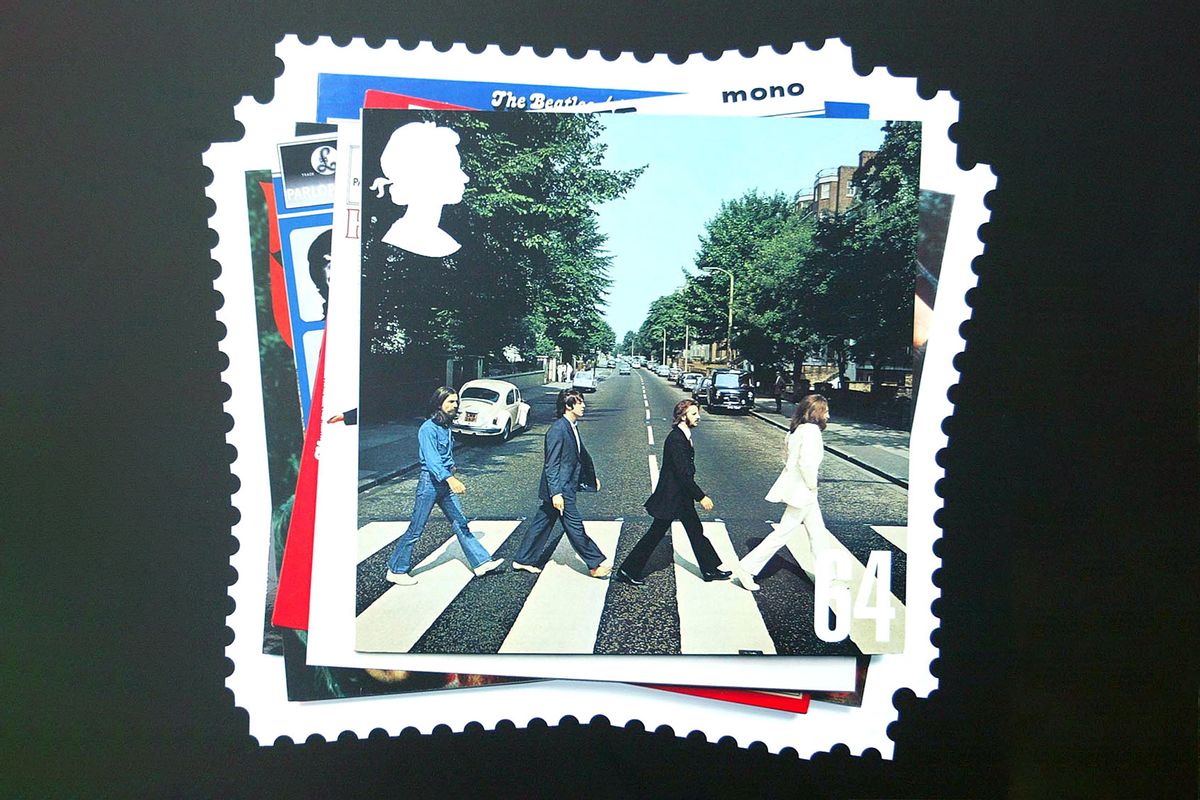

With masterworks such as the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” (1967) and Pink Floyd’s “The Dark Side of the Moon” (1973) engineered and produced in its environs, EMI Studios had already cemented itself as a historical landmark of sorts. In 1976, studio head Ken Townsend boldly recast the facilities as Abbey Road Studios in keeping both with the building’s famous address and the album — and its legend-making cover photo — that punctuated the Beatles’ spectacular career.

As Hepworth’s engrossing book comes to an end, he wistfully captures the image that greets tourists as they wind their way from the St. John’s Wood tube line to 3 Abbey Road. “It’s a lovely evening,” he writes, “and as I make for the station the first teenagers of spring are gathering, waiting for their turn on the zebra crossing.” It’s no great leap to imagine that as long as human beings love music, they’ll be making that fabled pilgrimage, walking in the footsteps of giants for centuries to come.

Love the Beatles? Listen to Ken’s podcast “Everything Fab Four.”