America and the “Heathen”: How we set ourselves apart from “sh**hole countries”

The story of the “heathen,” writes Stanford religious studies professor Kathryn Gin Lum, in her new book, “Heathen: Religion and Race in American History,” is a familiar one. It’s a story “about how Americans have set themselves apart from a world of sufferers, as a superior people and a humanitarian people — a people who deserve the good fortune they have received and have a responsibility to spread it to others.”

The necessary center of that story is the idea of “the heathen”: whether in its historical sense of people holding the “wrong religion” or its contemporary incarnation as a pitiable “third world” other, but always a figure in need of transformation and salvation. Under the supposedly beneficent mission of offering that salvation, Gin Lum writes, the concept has served as a wide-ranging “get out of jail free ticket” that “renders any harm excusable if done in the name of eradicating wrong religion.”

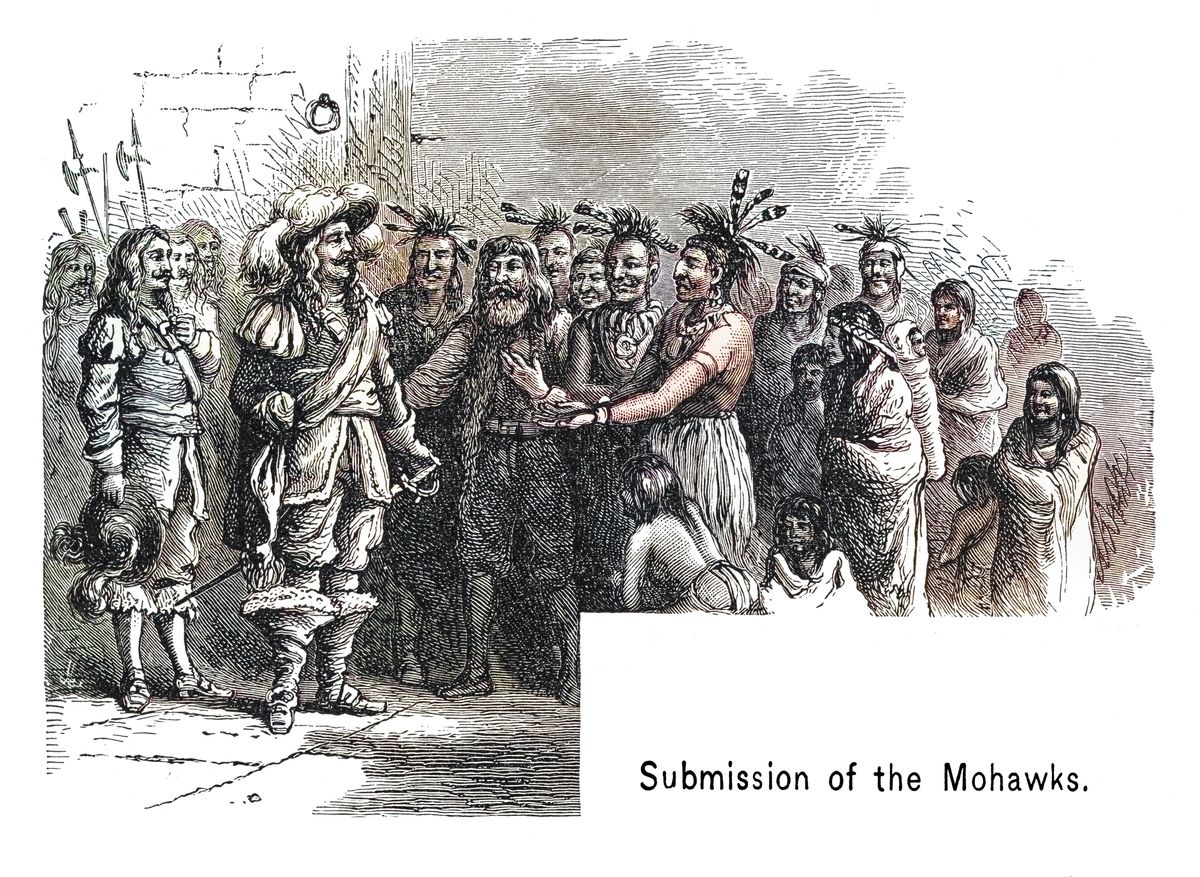

“Heathen” is a story about religion but also about race, colonialism, empire and identity — particularly American identity. The concept of heathenism was used to rationalize the slaughter of indigenous people, the burning of “witches,” the enslavement of Africans, the exclusion of Chinese immigrants, the abduction of Native American children and the usurpation of U.S. territories and colonies’ right to self-rule. In some ways, Gin Lum notes, the idea of heathenism is a large part of the origin story of the American concept of race.

RELATED: From the Pilgrims to QAnon: Christian nationalism is the “asteroid coming for democracy”

But it’s not merely a historical notion either. “Just because the word ‘heathen’ fell into disrepute does not mean that the mental maps through which Americans envisioned the heathen world similarly disappeared,” Gin Lum writes. It’s there still in the softer language Christian missionaries use today, as well as the corresponding secular discourse wherein “the poor and needy heathen has been reborn as the starving child living in the ‘third world.'” It was certainly there in early 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic was blamed on slightly modernized accusations of “heathen” practices in China.

The notion of the heathen hasn’t always been fixed or universal. Abolitionists and people under colonial rule have long turned the term back on itself, pointing out that American saviors have long been in thrall to idols of their own. Heathenism is also one of America’s most enduring foils, shoring up the country’s fragile sense of who we are. “The heathen world is precisely this: an elastic realm of individual-less Others who reflect back to Americans, as in a fun-house mirror, the selves they wish to deny, pity, control, or romance,” writes Gin Lum. “As long as Americans are not the interchangeable child starving overseas — as long as they are the ones putting money in the offering plates for the poor heathens in Africa or Asia, they tell themselves they are blessed.”

Gin Lum spoke with Salon this June.

Could you talk about what inspired this book?

There’s both a personal and an academic story to where the book came from. From a personal standpoint, I’m the daughter of Chinese immigrants and I grew up in a conservative religious tradition, with the belief that people from China who did not receive the gospel were heathens. So I grew up believing that if I hadn’t been so lucky to be born in the U.S., to a Christian family, I would have been in “heathen China” and bound for hell.

I grew up in a conservative religious tradition, believing that if I hadn’t been born in the U.S. to a Christian family, I would have been in “heathen China” and bound for hell.

I wrote my first book about hell, so you could say I’ve been grappling with questions about hell and the heathen for a long time. I write in the book that as a child, I could have been a primary source for myself as a historian now. As an adult, I could be a primary source for myself because the people I write about are trying to grapple with these things continually, as I still am. So I guess you could say this book is the attempt of a historian to understand myself and my people — people understood to be heathens in the history of this country.

From an academic standpoint, I was writing an undergrad thesis 20-something years ago on admission to Gold Rush-era California and looking at missionaries to the Chinese immigrant population and to the Euro-American population. I was struck by how much the Chinese were constantly referred to as heathens. Then I came across this 19th-century missionary map of the world that color-coded the world by religion, and was struck by how much of the world was colored gray for “heathen.” On one hand, it’s this term applied to the Chinese population, but on the other hand, it incorporates the vast majority of the world. I was really interested in what it is about this category that is so capacious and also so politically useful.

What is a heathen? Is there a way to define the term, given how widely it’s been used to paint so many different places and people?

The term “heathen” is the rough Germanic translation of the term “pagan,” which originates as a description of people in the ancient Greco-Roman past who failed to accept Christianity. It refers to the people “wandering in the heath,” understood to be on the outskirts of society, continuing to worship Thor, Odin and the old gods. Then that term takes on a much wider use as Europeans and Euro-Americans begin to realize there are many other people in the world who hold many different kinds of beliefs. Often, the term refers to people who hold “wrong religion.” But as I tried to show in the book, “wrong religion” manifests in many different ways, so the heathen comes to incorporate people who supposedly don’t know how to take care of their bodies, don’t know how to take care of their land, don’t have any progressive history, so to speak. It incorporates much more than just interior beliefs.

You open the book by citing a recent essay that invoked heathenism — and the necessity of converting “heathens” — as justification for the deaths of First Nations people in Canada who were removed to residential schools meant to assimilate them.

That story came out a year ago with the discovery of indigenous children’s graves in Canada. It was a troubling article, from my perspective, as a way of almost justifying the deaths. I think the author actually says that “whatever sacrifices were exacted in pursuit of that grace,” including the extinction “of a noble pagan culture,” is worth it. That’s what I call the “Get out of jail free” card: the use of this concept of saving the heathen to excuse all manner of atrocities. The residential school system was justified as a means of Christianizing heathen children; enslavement was justified as a means of Christianizing supposed heathens from Africa. This “heathen ticket” has been a very effective rationalization, as one of my colleagues puts it, of blessing the brutalities Americans have engaged in, in the name of helping other people.

How does the concept of heathenism play into Christian nationalism?

The question of what is America and who gets to be an American is at the heart of part two of the book, about the body politic. And the question there is whether America is a Christian nation, and should we be allowing “heathen” people into the body politic? That was really the question around Chinese exclusion in the late 19th century, which raised a lot of the same issues that come up today around the anxieties of white Christian nationalists about what this nation is and who can belong in it.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

The term heathen was one of the most common derogatory terms applied to the Chinese in the late 19th century. A lot of scholarship on Chinese exclusion focuses on reasons for exclusion that concern labor competition and economics. That’s important, just as today it remains extremely important in conversations around replacement theory, for instance. But the rationalizations that religion offers to justify these economic claims are crucial.

In the late 19th century, there were Christians saying that America is and needs to remain a Christian nation, and allowing the immigration of heathens into this nation threatens the bedrock of who we are. We’re supposed to be an example for the rest of the world of what Christian civilization should look like. But the fact that they’re so worried about the immigration of “heathens” reveals how unstable the foundations are of this supposed city on a hill. They’re actually worried that Christians are going to be converted to heathenism faster than supposed heathens can convert to Christianity. So for me, it reveals how tenuous this identity of white Christian nationalism is.

You discuss how the term “heathen” has been adapted over the years to apply to many different groups: Native Americans, enslaved people, Chinese immigrants, subjects of missionary work in other countries and even later waves of European immigrants to the U.S. Can you talk about the history of how heathenism has been tied to race?

By the late 19th century, there were already Christians saying that America needed to remain a Christian nation, and that allowing the immigration of heathens threatened the bedrock of who we are.

Oftentimes, when we think about race, we think about it in terms of hierarchies based on supposed physical differences that are obviously socially constructed, but which try to distinguish between groups. The thing about the heathen is that it collapses racial hierarchies: It collapses everyone below the white Christian colonizer into one category. That is a racial process, too. I’m building on the work of the scholar Sylvester Johnson in his book “African American Religions,” where he argues that race is a process of separating the European from the non-European, the colonizer from the colonized, and the governor from the governed. The heathen is essential to that process of separation.

So often when we think about race, although it’s socially constructed, it’s understood as an inherent quality that can’t be changed. But the heathen is a changeable figure: the heathen can be converted, the heathen can become the Christian. So some scholars have seen it as not a racial category. I think that the changeability of the heathen is exactly what makes it so powerful in the separation of the world into these binaries of European/non-European and governor/governed. Again, it’s that “Get out of jail free” ticket: the notion that people can be changed to be something else rationalizes European and Euro-American interventions in broad regions of the world under the heading of saving heathens. We don’t use the term heathen much anymore, but that doesn’t mean the ideas underlying this binary view of the world have disappeared. They’ve just become subsumed under the language of the “third world,” developing nations or, in religious contexts, of “frontier peoples” or “unreached peoples.”

Before getting to the more modern, polite versions, is it fair to say that the concept of heathenism has basically been used as justification for empire or subjugation?

You can certainly say the term has been used for that, but I don’t want to discount the motivations of missionaries, volunteers and humanitarians who believe they are helping people and, in some cases, are. I don’t want to just boil it down to a justification for empire, because I don’t think everybody using the concept of the heathen is doing it with that in mind. But as I said before, the idea of bringing salvation blesses brutalities. So even if that’s not the motivation, it has the effect.

You write a lot about how both the language and the general approach of missionary work has changed over the past century.

Well, it changes and it doesn’t. There were increasing challenges to the concept of the heathen by the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1930s some mission organizations basically abandoned the term and said that the point of missions was not to convert people or save souls but to help the human conditions people are living in. But there still are mission organizations that continue to see the world in this framework of unreached peoples and some of the language completely parallels that used in the 19th century, even if the term heathen isn’t used.

Can you talk more about how these ideas show up today in discussing “developing nations” and “white saviorism”?

To go back to the question about whether this is just a way of justifying empire, I would make an analogy to the ways we think about racism and the difference between critical race theory, which understands racism as embedded in systems, and the ways that people who push back against CRT think that you can’t be racist if you don’t intend to be racist. There are people who say or believe they are not doing harmful things, but helpful things. But at the same time, they are constructing long-lived systems that have divided the world into this stark us-versus-them — the white savior and everyone else. And these systems remain, even if the motivations are “positive.”

A lot of the early war coverage was about shock: Ukraine is not supposed to be the “heathen world” or a “shithole country.” It’s supposed to be Europe.

I write in the book about the “third world” or developing nations as euphemisms for this figure of the heathen, in both the religious and the secular realm. I live in Silicon Valley so I am very exposed to Silicon Valley tech-saviorism, which I see as very connected to this rhetoric, even though those people would be horrified to hear that. The idea that you can do good for others while also helping yourself traces back to this dynamic in the 19th century, that going out and saving the heathen is a way of ensuring your own salvation. Now, in this secularized understanding of it, Silicon Valley is all about doing good and lining your pockets at the same time. Within tech salvationism there continues to be this stark binary between people who have technology and can change the world and those who are the receivers of that, which also traces back to many assumptions that have been attached to the figure of the heathen.

You also write about how the language of “heathen countries” has been replaced by Donald Trump’s talk of “shithole countries.”

If you Google Trump’s language around “shithole countries,” you can find maps that show America and Northern Europe as the only parts of the world that are not “shitholes.” And you can see that in some of the media and social media coverage around the war in Ukraine. Particularly at the beginning of that crisis, a lot of the coverage was shocked, because Ukraine is in a part of the world that is not supposed to be the “heathen world” or the “third world” or “shithole countries.” It’s supposed to be Europe. So people were explicitly saying things like, “It’s shocking to see this happening here, to people with blond hair and blue eyes, in a civilized country.” It wasn’t supposed to happen in a “civilized country,” it’s supposed to happen elsewhere.

In 2019, when the Vatican hosted a synod for people from the Amazon region of South America, it sparked a fierce backlash from some right-wing Catholics who used virulently anti-indigenous language to condemn an effort by the church to be more inclusive. Have you seen things like that show up: corners of Christianity re-embracing old-school “heathen” language?

Not many corners of Christianity use heathen terminology out loud. But even if they don’t, this idea that salvation is in Christ alone provides the stakes for missionary work. It’s a way of demarcating the boundary of what it means to be Christian and what is outside of that. That’s really what the concept of the heathen is about. What is the not-Christian like? What does that identity entail? To blur that boundary, to say we are going to bring other traditions into that conversation, traces back to what I was saying about Chinese exclusion: it strikes at the heart of these anxieties about: Who are we? What is the border of our identity? What’s the difference between the “us” and the “them”? That’s where you see this language emerge.

It’s really important, in these debates over becoming more “respectful” of other traditions, to look at Christians from communities that were historically deemed heathen. In global Christianity, people from the “heathen world” who adopted Christianity have done so with extremely clear eyes. They’re not people who were just coopted and colonized. They are people who see the hypocrisy that white Christians have often brought and they have provided alternatives. So the question of what it means to respect another culture or tradition, and to put Christianity in conversation with other traditions, they live that out on the daily. And they are much less interested in the border policing that white Christian nationalists get all up in arms about, about who the “us” and the “them” are.

How does this idea show up in debates about how the U.S. grapples with our history and our racial history in particular?

A lot of this story is about people who think they’re doing really good things. I think that is analogous to how people push back against CRT by saying, “We’re not racist, we don’t have bad motivations,” but then fail to see the systems they have created, that they participate in, which uphold whiteness as superior. You can believe you are not doing something harmful while also benefiting from and perpetuating systems that are doing harm. I think the story I’m telling here helps to explain that by bringing religion into the conversation, because one of the most powerful things about religion is the way that it blesses things that are really ugly. Religion can provide language to make things look good.

You can see that with American exceptionalism. America is exceptionally violent. It’s exceptionally racist. So how can white Christian nationalists claim that it’s exceptionally good, a city on a hill? It’s the power of religion that does that.

Your postscript includes a fascinating discussion of how the concept of heathen-ness was deployed during the pandemic.

I was finishing the book as the pandemic hit, and originally wasn’t planning to write anything about it. But I couldn’t ignore how much what I was writing about seemed to be everywhere. Particularly as someone who’s Asian American, the language around “the Wuhan flu,” and the anti-Asian violence, the anti-Chinese hate, just paralleled so much of what I saw in the history.

In one of the articles I cite in the postscript, the author writes something to the effect that “The Chinese wet markets must go,” which sounds like a direct echo of Denis Kearney, an anti-Chinese demagogue in the late 19th century, whose famous refrain was, “The Chinese must go.” That refrain from Chinese exclusion was used again in 2020 to scapegoat the Chinese as being responsible for the pandemic, because they’re “backward,” they have “dirty” eating habits, they believe in “magical” practices connected to food. All of this was blamed for starting the virus and spreading it to the world.

Language from the time of Chinese exclusion was used in 2020 to scapegoat the Chinese as responsible for the pandemic: They’re “backward,” they have “dirty” habits, they believe in “magical” practices regarding food.

At the same time, I also saw a really interesting way in which America was held up to what I call “the heathen barometer.” I explain that as a way to identify heathenism in the world and to call out things that appear to be “heathen” at the heart of America itself. With the COVID pandemic, I saw what I call a “third world barometer,” where people were completely shocked that there wasn’t enough PPE, there wasn’t enough hand sanitizer. People were saying, “It isn’t supposed to be like this. America isn’t a third world country. Why are we acting like one?” For me, that was this long history manifesting again in really stark ways.

At the end of the book, you come to this powerful conclusion: The concept of the heathen as either scary or pitiable is used to make Americans feel blessed by comparison.

Exactly. It’s almost like deflection. It’s the same thing we were talking about with Ukraine: “This is not supposed to happen here.” But then moments like the pandemic expose that. I think that’s where that heathen barometer has been so powerful as a way of showing, actually, this has always been the case. America has always had its own idols, whether that’s the idolatry of guns, of money, of white supremacy. These are all things people have called out to criticize the hypocrisy of Americans claiming that, no, this just happens in the heathen world. In the 19th century, Frederick Douglass drew on the heathen barometer to say: How can we send foreign missionaries overseas to save the so-called heathen when white Americans are bowing at the altar of King Cotton? It rips the veneer off white American exceptionalism and shows this is happening here.

Is the idea of “true religion” versus “heathenness” a missing piece in the conflicts we’re having over history?

A lot of scholars have looked at the relationship between religion and race, so I don’t know that it’s “missing,” though maybe it hasn’t been described in this way. But I think once you see it, you can’t unsee it. It’s everywhere. Maybe that can contribute to conversations about where we go from here.

I’m a historian, not a theologian or an ethicist. But a question I often get when I talk about this work is, “What are we supposed to do?” I can’t give you answers for that. I just want to tell the story of what I’ve seen people doing. But I hope it causes people to think about it for themselves. Because I understand this as humans doing something with religious truth-claims, I think humans can change that too. This is not a story that can’t be changed.

Read more on religion in American politics: