At last, a Yoko Ono retrospective free of The Beatles blame game

The first large image you see when entering the first gallery of “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind,” the massive retrospective of Yoko Ono’s work currently on exhibit at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, is the large reproduction poster for her debut performance at Carnegie Hall, which took place on Friday, November 24th, 1961. It’s adjacent to both “A Work to Be Stepped On” (self-explanatory!) as well as “Waterdrop Painting (Version 1),” where the artwork is positioned on the floor beneath a water bottle. A nearby label explains that the work will be “activated intermittently” by staff.

The exhibition displays over 200 different works drawn from the multiple disciplines Ono has engaged with across almost seven decades, whether film, music, conceptual or performance art, and also includes her continuing peace activism. “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” is curated mostly chronologically and within that, organised around major projects. This curation is both logical as well as gently instructive, because it allows visitors to easily follow the evolution of her work, as well as see which themes and ideas are reused and refined and continue to grow.

The exhibit features many of Ono’s most influential and/or well-known pieces, such as films “The Fly” and “Film No. 4 (Bottoms),” the latter of which was banned by the BBC because it is one hour and 10 minutes of famous people’s butts. Another section features artifacts and photographs from Ono’s “Cut Piece,” where she sat onstage and invited the audience to come and cut away parts of her outfit. That performance was part of a group called “Strip Tease Show,” part of which was three chairs that were placed onstage and remained empty until they were removed. We see the chairs, and we see the script that directed the events.

Other highlights include a sterling silver exemplar of “Box of Smile,” which is a small box containing a mirror inside. It’s a tiny element within such a large body of work, but a perfect example of how Ono creates the intention or the suggestion, and then opens the possibility for the viewer to complete the piece — in this case, by, well, smiling. Nearby, a series of military helmets hanging upside down from the ceiling at various levels contains small blue puzzle pieces representing a piece of the sky.

There’s also an example of “Ceiling Painting,” where the viewer is supposed to climb a ladder up to the top, where they’d find a magnifying glass which they’d use to see a very tiny YES painted on the ceiling — except that there is sadly no way to allow that to happen because of insurance, and safety, and structural integrity of the art. Other greatest hits are “Half-A-Room,” where everything in the room is both painted white and cut in half, and an example of “Acorn Piece,” when Ono and her husband (more on him in a bit) sent acorns to world leaders, asking them to plant them as a gesture for peace.

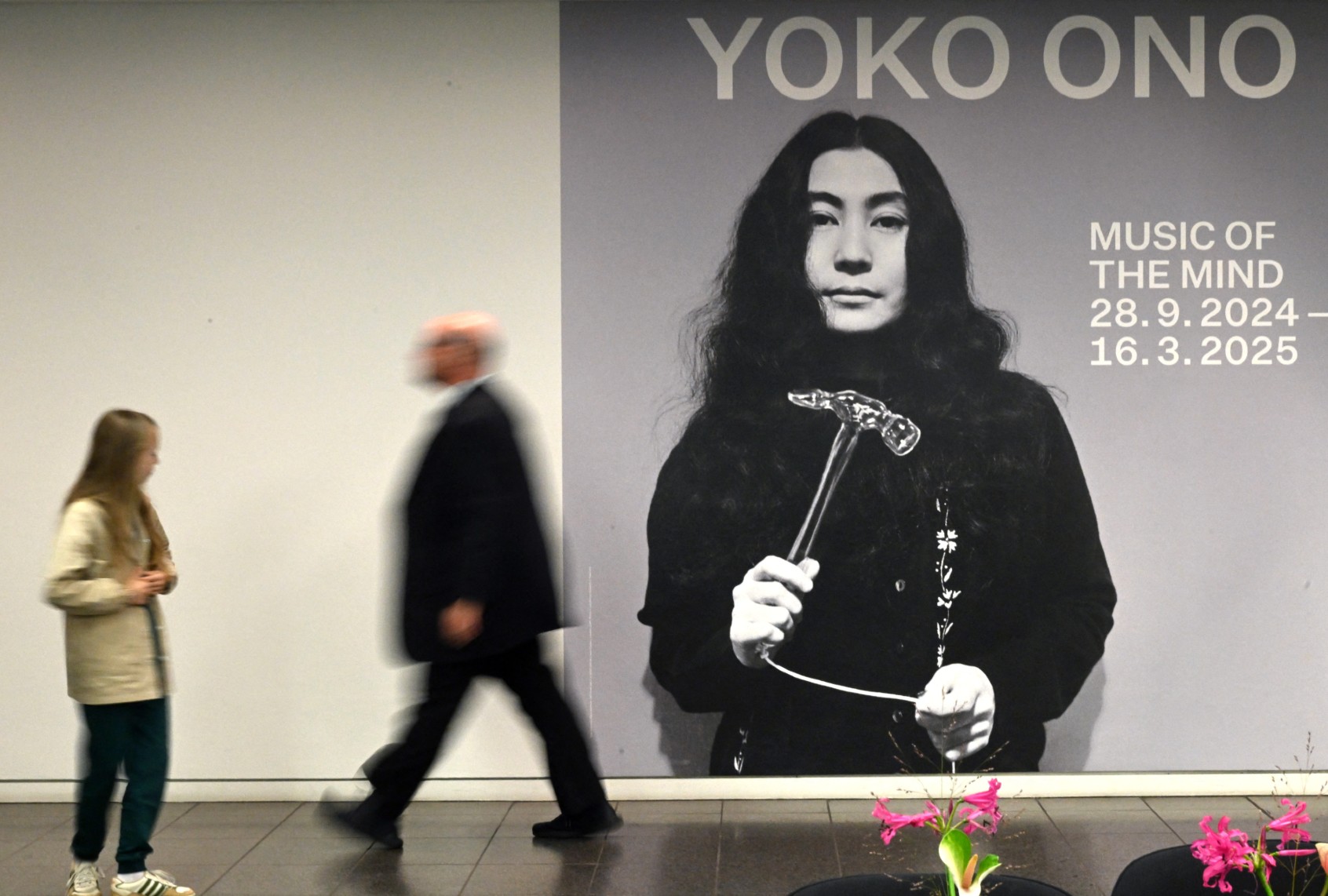

(INA FASSBENDER/AFP via Getty Images) A woman stands in front of the Yoko Ono “Cut Piece”, 1965, during a press preview at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Duesseldorf, western Germany on September 26, 2024.

There are also multiple opportunities to physically engage with the work beyond one’s mind. When you arrive at the 4th floor, you’re greeted by a series of olive trees that Ono calls “Wish Trees.” There are a number of these in various locations (and one online) where you’re encouraged to write a wish or a thought on a tag and hang it on one of the trees. Immediately adjacent is “My Mommy Is Beautiful,” an installation in which you’re encouraged to write about your mother and to add it to the massive quantity of love notes and tributes and carefully drawn sketches of people’s mothers. These aren’t new artworks, but they serve as an easy, friendly entry point to Ono’s way of thinking and creating art.

Want more from culture than just the latest trend? The Swell highlights art made to last.

Sign up here

Later on in the exhibit, four black bags hanging on clothes hooks invited the visitor to experience “bag-ism,” where you’re instructed to take off your shoes and climb into a full-size cloth bag (there were also child-sized ones). The original instructions (as posted adjacent) were to climb into the bag, remove your clothes, sit there, then put the clothes back on and emerge from the bag. Even considering simply taking your shoes off and getting into a bag in a room full of strangers was more daunting than it might seem — you’ll never see these people again, they can’t see you, you’re in a bag! — It must have been overwhelming for the performers when it was first presented in front of an audience.

Accidental artwork sounds like the kind of thing Yoko Ono would be very pleased with.

Then there was Mend Piece: “While you mend | think of mending the world.” Visitors enter a space holding tables filled with pieces of broken ceramic dishes. Your first inclination will be to try to solve it like a puzzle, where you’ll search for the pieces that match, the teacup or bowl you can reassemble. Except that there deliberately aren’t any matching pieces, and then your brain will have to find a different way to assemble them, using nothing but glue and string. I sat with a friend as we talked about the experience of trying to figure it out and what to assemble and what we wanted to make; it was like the opposite of a paint-your-own-pottery place, or maybe one run by Fluxus, the avant-garde artist collective Ono was involved with. I used shards from bowls and my end product looked like a lotus flower, a thing I did not realize until someone pointed it out. Accidental artwork sounds like the kind of thing Yoko Ono would be very pleased with.

(DANIEL LEAL/AFP via Getty Images) An artwork entitled “Apple” 1966, is pictured during a photocall to promote the exhibition “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” at Tate Modern in London on February 13, 2024.

You get halfway through the exhibit before you run into an image of John Lennon. It’s at the beginning of the segment titled “London Years,” where exhibit signage helpfully informs you that during Ono’s time in London (1966-1971), she “…connected with artists, musicians, and writers, including John Lennon, her future husband and longtime artistic partner.” That the B word (Beatles, in case this wasn’t obvious) was nowhere near this description felt hopeful and redemptive.

I was a 20-something Beatles fan who made her first pilgrimage to “Beatlefest” (think ComicCon, but 100% Beatles or Beatle-related) at a New York City hotel in the late ’70s. In between the tribute bands and memorabilia vendors, one of the big attractions was screenings of various rare or bootleg film footage, screened in cavernous hotel ballrooms. Back before YouTube, these were the only way most fans would have access to this kind of footage if you weren’t a rich private collector.

But this was the first time I physically experienced the deep dislike — I didn’t recognize it as blatant misogyny until years later — engendered from Beatles fans towards the person upon whom the collapse of the Fab Four was blamed (and probably still is in some circles). As soon as Yoko came into view — it was “Let it Be” outtakes — the room dissolved into hisses and more than a few boos, and not just from the (mostly) men present in the room. It probably wasn’t everyone, but it was pervasive and disturbing, and it made an impact on me. As an average suburban kid, The Beatles were my gateway drug into Yoko Ono, and the negative vocal reaction — which I initially simply thought was dumb, like a playground taunt — only made me want to learn more about a woman who could disturb an entire room of grown men that badly.

A friendly librarian tipped me off that the main branch had a not-for-circulation copy (because of its Beatle-adjacency, it was explained) of Ono’s “Grapefruit” and suggested I make use of the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature (a pre-internet index of magazines and newspapers that was absolute magic) to find more articles about her, perhaps in art publications. At age 15, I knew that I didn’t understand everything about Yoko Ono’s work — I didn’t even know if I liked it — but I also didn’t necessarily understand Arthur Rimbaud, “Desolation Row,” or “Howl.” That didn’t mean I wasn’t going to try.

As an average suburban kid, The Beatles were my gateway drug into Yoko Ono, and the negative vocal reaction — which I initially simply thought was dumb, like a playground taunt — only made me want to learn more about a woman who could disturb an entire room of grown men that badly.

At the MCA exhibit, I hated the fact that I was running a subconscious tally in my head that noted that Yoko Ono played Carnegie Hall before The Beatles did, and that she was an established and influential artist of international renown long before she met John Lennon, that I was checking the years listed against the timeline of The Beatles’ career in my head, as some kind of defense against the boos and the hisses back in that hotel ballroom. “She was doing these things while John was onstage in Hamburg in his underwear with a toilet seat around his neck,” I muttered under my breath. And yes, that is also art, but despite the existence of ironic JOHN LENNON BROKE UP FLUXUS t-shirts, the demonization didn’t work in reverse; it never does.

This is not new information. These were facts that were true when the pair met, and true when she was captured by the cameras in “Let it Be” and true when that room full of Beatles fans in the late ’70’s decided to vocally and publicly register their displeasure at her existence adjacent to their hero. It was also always true that she had nothing to do with causing The Beatles to break up and that she was, and remains, a visionary, a revolutionary, and a highly accomplished and influential artist.

“Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” is an exhibit originally staged at the Tate Modern in London in 2024 and is now being exhibited at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art until February 22, 2026, before moving to the Broad in Los Angeles beginning in May of 2026.

Read more

from music columnist Caryn Rose