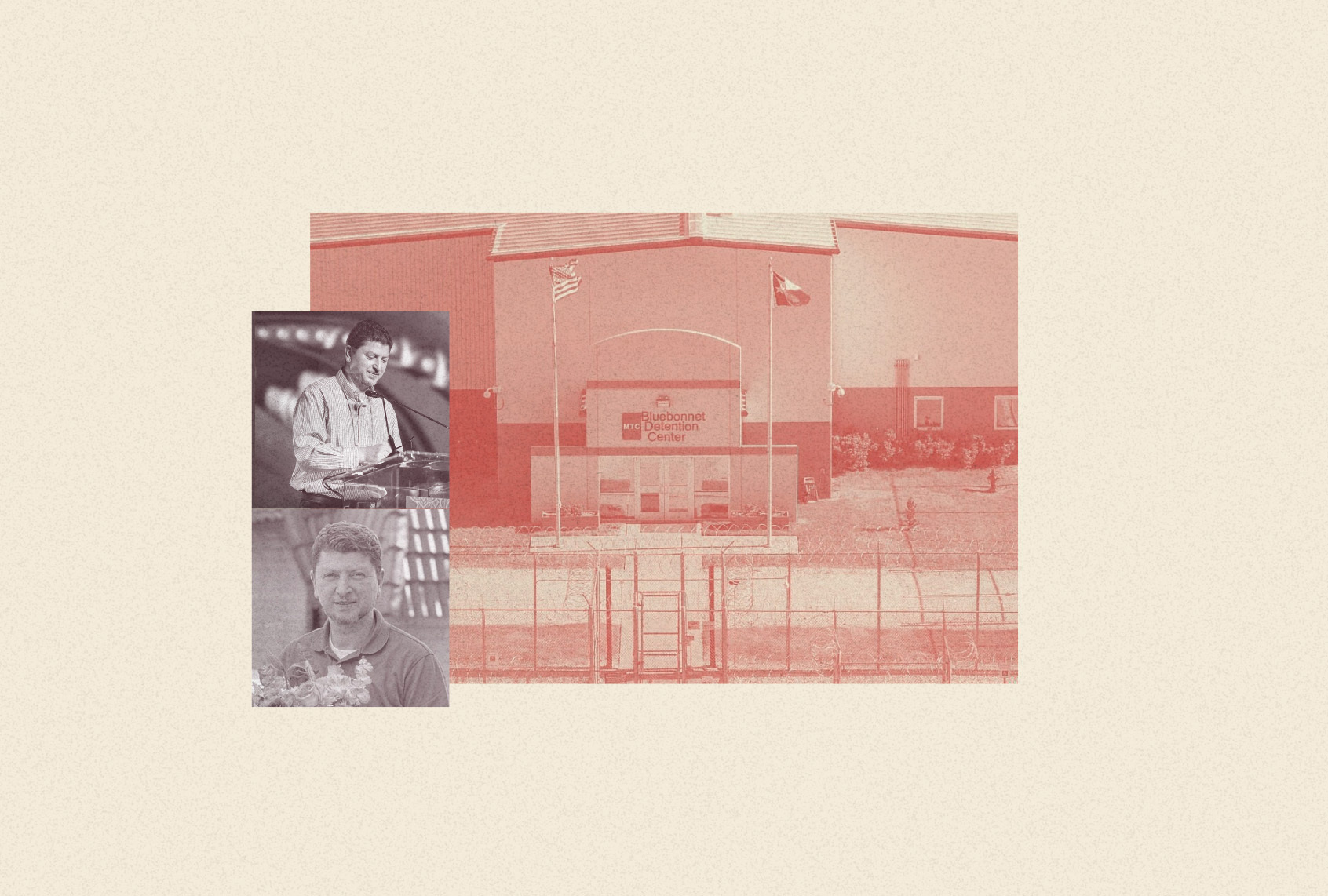

ICE upends Dallas Muslim community with detention of local leader

Marwan Marouf’s friends say that he’s the kind of Texan to show up at your door when hardship strikes with a bag of groceries, a smile and a helping hand.

To Noor Wadi, that meant the Muslim Dallas community leader has helped her feel at home in the North Texas city, stuffing her with cheese pies and checking on her after she moved from her home state of Missouri in 2011. To Imam Omar Suleiman, that meant Marouf was the first person to pick him up and show him around Dallas when he landed there that same year. To countless others in the community, that’s meant being a constant presence, visiting community members in the hospital, organizing blood drives, creating one of the largest Muslim Boy Scouts troops in the Texas region, and offering advice to visitors to his office at the Muslim American Society community center he helps run in Dallas.

“To say that Marwan is the heart of the community is not an exaggeration,” Suleiman, an Islamic scholar and civil rights activist who has been friends with Marouf for more than 30 years, said in an interview.

That all changed in September.

On the morning of Sept. 22, agents with Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrested and detained Marouf just moments after he dropped his 15-year-old son at school. Since then, Marouf has remained in detention at the Bluebonnet facility in Anson, Texas, for more than 50 days, separated from his wife and four sons. His family and community have been left grieving his absence, but as his case progresses through immigration court — with a pivotal hearing that could determine whether he remains in the United States scheduled for this Thursday afternoon — they remain firm in pressing the government for his release.

“We’re really holding on to hope and trying to fill that gap to keep the community optimistic that we will have him back soon,” Wadi, a federal criminal defense lawyer and leader of the Justice for Marwan campaign, told Salon. “It’s been hard to start to come to terms [with the fact] that this is a longer process.”

The morning Marouf was detained was a chaotic one. Within the 10 minutes it took to drive between his youngest son’s school and the community center, seven unmarked ICE vehicles pulled him over and officials detained him, according to Mohammed Marouf, the MAS fundraising director’s eldest son. His second son would later go with his father’s friend to the ICE facility in Dallas to collect his belongings, obtaining the green card denial letter and detention notice dated Sept. 22 in the process.

“Marwan’s case reflects a deeply troubling pattern we are seeing across the country, where long-time residents with deep community ties are targeted under the banner of a broader ‘immigration enforcement’ campaign.”

“He has been struggling quite a bit with his health, physically and mentally,” Mohammed Marouf told Salon. His father has Brugada syndrome, a serious heart condition marked by abnormal rhythm that stressful situations can exacerbate. “At the end of the day, though, he is determined to find a silver lining in this awful situation.”

Marouf’s arrest, though a huge shock, wasn’t entirely unexpected, Mohammed Marouf recalled. Just days prior to his arrest, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services had denied Marouf’s permanent residency application. Plus, ICE had shown up at their home in 2019 after his parents filed green card applications. With the Trump administration accelerating its crackdown on immigrants across the country, both his father and mother — who is also an immigrant and was out of the country at the time of Marouf’s arrest — had been on high alert.

A Palestinian born in Kuwait and raised in Jordan, Marouf first came to the U.S. on a student visa in 1993 to attend college at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. There, he would become a pillar of the community, building a youth group that Suleiman participated in. In 1996, he moved to Dallas, the place where he would earn his master’s degree, begin volunteering in the community, meet his wife and start a family. When his sons eventually came along, he involved them in nearly every community service activity he participated in.

“He always included us as part of the contribution, and that’s to be honest, what raised us into the men that we are today,” Mohammed Marouf said, noting that the 54-year-old has never received more than a small traffic infraction in his life.

The government first accused Marouf of overstaying his visa, the allegation coming via the notice to appear in immigration court that he received during his arrest. It has also claimed that Marouf did not have a valid visa when he last reentered the country following a 2011 trip to Jordan. Just moments before an Oct. 23, hearing in Houston’s immigration court, the government leveled a new claim: Marouf solicited funds for and provided material support to the Holy Land Foundation, a massive charity that raised funds for humanitarian aid in Palestinian territories, between 1994 and 2001.

“This is a person who has always served our community.”

In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Holy Land Foundation received a Tier III terror group designation, which is given to an entity that has engaged in terrorist activity but has not been formally designated a terror organization. The designation came as the nation broadened its terrorism definitions under the 2001 USA PATRIOT Act and was shut down. In 2009, a federal jury found it and several of its leaders guilty of funneling millions of dollars to Hamas, the government of the Israeli-occupied Gaza Strip, through humanitarian aid donations to Palestinian charities that Hamas controlled. Human Rights Watch has criticized the prosecution as “prejudicial.”

Marouf’s lawyers, family and friends deny all of the government’s claims as false. Mohammed Marouf particularly decried the claims that his father supported terrorism, noting that Marouf’s contributions merely amounted to volunteering to watch children at Holy Land Foundation fundraisers in the ’90s and making a small monthly donation to sponsor a Palestinian orphan.

“Imagine 20 years later, the government is still coming after you for that,” he said.

After an Oct. 23 court hearing, Immigration Court Judge Abdias Tida sustained all of the Department of Homeland Security’s charges against Marouf. The claims also strip Marouf of his eligibility for voluntary departure, which, unlike deportation, allows someone to re-enter the country after fulfilling legal criteria.

Thursday’s final “individual merits” hearing will weigh his applications for permanent residence and other forms of relief, and, if his legal team is successful, allow them to revive a habeas petition seeking to have him removed from ICE detention.

“Marwan’s case reflects a deeply troubling pattern we are seeing across the country, where long-time residents with deep community ties are targeted under the banner of a broader ‘immigration enforcement’ campaign that appears to revisit stale allegations without new evidence or cause,” Marium Uddin, legal director of Muslim Legal Fund of America and an attorney representing Marouf, said in an email. “We’re watching the politicization of immigration proceedings (not new), which shows us how our immigration system can lose sight of its own humanity.”

Start your day with essential news from Salon.

Sign up for our free morning newsletter, Crash Course.

“We intend to do everything we possibly can to put on the absolute strongest, most integrous case possible, to show the judge that Marwan is most deserving of every form of relief (resulting in his green card),” she added.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for comment.

Since Marouf’s detention in September, the community has been reeling. The situation has been worsened by the detention of Yaakub Vijandre, a local photojournalist and DACA recipient documenting Marouf’s case, and British Muslim journalist Sami Hamdi, whose visa was revoked while touring the U.S.. All three men have supported Palestinian rights.

But the upheaval and increased ICE presence hasn’t completely chilled community action. The day after Marouf’s detention, community members gathered at the MAS center for a town hall to process the loss. Mohammed Marouf said that neighbors and others who know his father have stepped up to help, offering home-cooked meals and other support in his absence.

A group of around 10 community members also started the Justice for Marwan campaign, a targeted on- and offline effort to keep Marouf’s story at the forefront until he is freed. They’ve led vigils and protests, reached out to local and state officials to push them to get involved, and started the “Because of Marwan” hashtag on social media, encouraging Texans to share the stories about how Marouf has impacted them.

“This is a person who has always served our community,” Wadi said, noting that people reach out every day to learn how they can help. “Now it’s our time to do what we can to help him back.”

A petition demanding Marouf be freed from ICE detention has garnered more than 17,000 signatures, while supporters have sent more than 60,000 letters via the Action Network to their Congresspeople pressing them to call for his release.

As his final immigration court date approaches, the campaign has called on supporters to contact his Democratic congresswoman, Rep. Julie Johnson, and urge her to launch a congressional inquiry, an elected official’s formal request for information about a matter, into Marouf’s case. A spokesperson for Rep. Johnson did not respond to a request for comment.

Suleiman underscored what’s at stake in and beyond Marouf’s case.

“So many people are unknowingly building the infrastructure of their own repression tomorrow,” he said, calling the case and the Trump administration’s broader immigration crackdown “an assault” on the basic human rights “this country claims to stand for.”

“It shouldn’t have to take the fear for your tomorrow to do what’s right for someone else today,” Suleiman said.

Read more

about ICE under Trump