Liverpool can’t keep winning games like this — or can they?

Let’s do a quick blind comparison of two Premier League teams from this current season.

Team A still hasn’t lost a game. In fact, it hasn’t earned a draw. In fact, it hasn’t even trailed in a game. We’re just five matches into the season, and it already has a five-point lead atop the table. That’s tied with one other side for the biggest lead through five games in the history of the Premier League. And the other team to do it? It won the title by 18 points.

Meanwhile, Team B has scored 11 goals and conceded five. That gives it a plus-six goal differential, the third-best mark in the league. At least 50 other teams in Premier League history have outscored their opponents by more goals through five matches, and the same holds true for goals scored and goals conceded. It’s good … but it’s not great. Last season, Tottenham had a better goal differential than this team through five matches, and they finished one place clear of the relegation zone.

So, which team would you rather be?

It’s a trick question, of course: Team A and Team B are the same team.

Liverpool are undefeated this season, but they’ve still only won one match by more than a goal. And even in that one, the season-opener against Bournemouth, they didn’t take the lead for good until the 88th minute.

Liverpool beat Newcastle on the road thanks to a goal in the 100th minute from 16-year-old Rio Ngumoha. They took down Arsenal with an 83rd-minute free kick by Dominik Szoboszlai. They needed a 95th-minute penalty from Mohamed Salah to beat Burnley. Virgil van Dijk headed in the winner in the 92nd minute of their Champions League opener against Atletico Madrid. And Hugo Ekitike‘s 85th-minute tap-in-turned-red-card secured a 2-1 win against Southampton in the Carabao Cup.

Liverpool have somehow been even better and much worse than anyone would’ve predicted at the start of the season. So, let’s ask the same question that rival fans seem to be screaming, week after week: They can’t keep this up … right?

– First-month grades for all 20 Premier League teams

– Soccer’s most stylish 2025-26 kits: The world’s best jerseys

– Early-season angst check: Who needs to be worried?

Why do Liverpool score so many late goals?

Whenever a team continues to win in such an improbable fashion, it is attributed to a club’s superior, never-say-die mentality. That was the case with Manchester United under Sir Alex Ferguson. It’s what happens with Real Madrid in the Champions League every year. And it frequently felt true with Liverpool under Jurgen Klopp — and now it seems true under Arne Slot, too.

The stats seem to back that up. Since the Premier League was created in the early 90s, Liverpool have won 43 games with a goal in the 90th minute or later — a whopping 13 more than any other side.

So, Liverpool are better at winning games late than everyone else — or are they? At least, I’m not sure that’s what that statistic is telling us. There’s a more economic explanation for it.

Liverpool have the third-most points of any club in the Premier League era. On the whole, Arsenal and Manchester United have been better than Liverpool since 1993, so those two clubs haven’t had to win as many late games. Then, when Manchester City and Chelsea entered the picture with their wealthy new owners in the 2000s, they typically had better and more expensive squads than Liverpool. Before that, they weren’t anywhere near as competitive as Liverpool.

So, Liverpool sit in that sweet spot where they won lots of games and therefore, they won lots of late games. But they also weren’t as talented as the other teams that won lots of games, so a higher proportion of their wins came from late goals.

There’s definitely an Anfield effect here — opposing players tend to agree that it’s the hardest place in England to play. So, if you combine that with the fact that, for most of the Premier League era, Liverpool have been competing with richer and better teams, then it makes sense that they’ve needed to use every minute of every game to keep up.

Now, that isn’t quite as true anymore. They spent a net of $309 million on transfer fees this past summer. They made $773m in revenue in 2023-24, and some estimates rank them as the fourth-most valuable club in the world after Manchester United, Real Madrid, and Barcelona. Per FBref, they have the sixth-highest wage bill in the world.

So what’s the explanation for all of the late winners this season?

Liverpool have been the best team in the league when the score is tied in the second half of matches. They’ve scored four goals and conceded zero — both best or tied-for-best marks in the Premier League. They’ve also attempted 28 shots (nine more than anyone else) and conceded only five. The 23-shot margin is by far the largest in the league; no one else is above 10. Part of the reason they’ve scored so many late winners is that they’ve heavily tilted the field whenever they’ve needed a late winner.

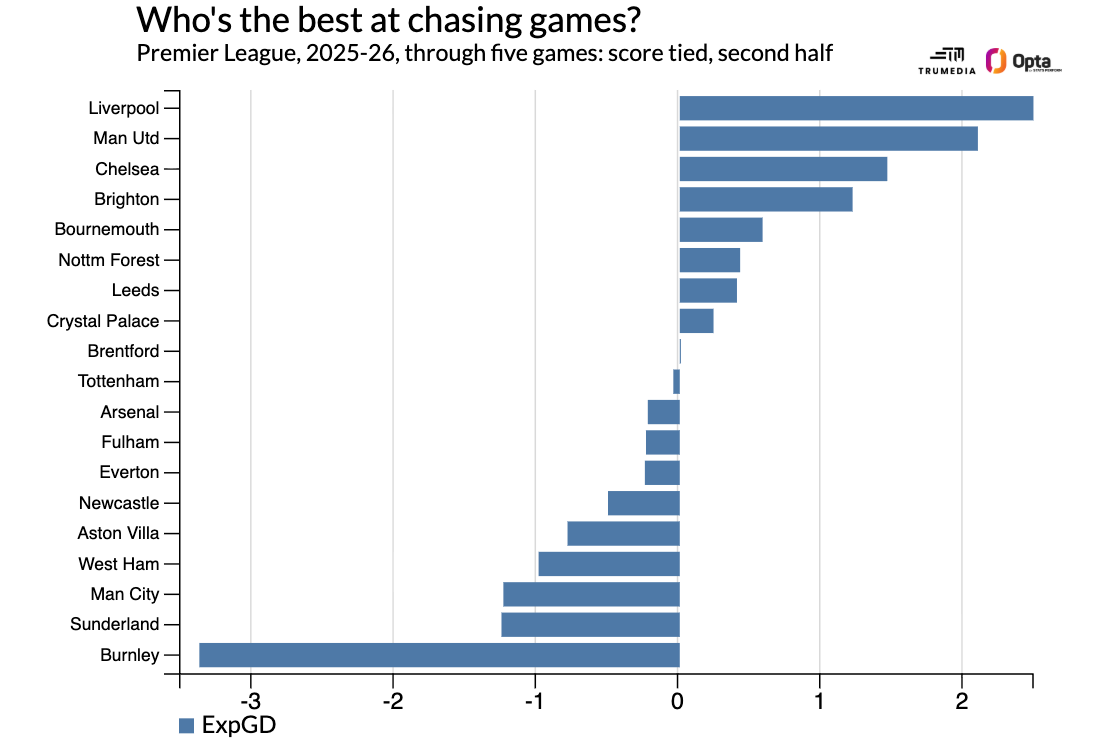

Here’s how it looks for the whole league when we compare xG (expected goals) created and xG conceded in the second half when the score is tied:

Liverpool have created 2.49 xG and conceded just 0.11 at this game-state. The defense allows almost nothing, while the attack creates a ton. That’s great, but it still doesn’t answer the bigger, more important question.

Why do Liverpool need all of these late comebacks?

There are two problems with all of these late-game, tied-score stats: (1) we’re already cutting a small sample of five matches into an even smaller one, and (2) not everyone has played the same number of minutes with the score tied in the second half. If you’re one of the best teams in the world, ideally, you’re not spending too much time there.

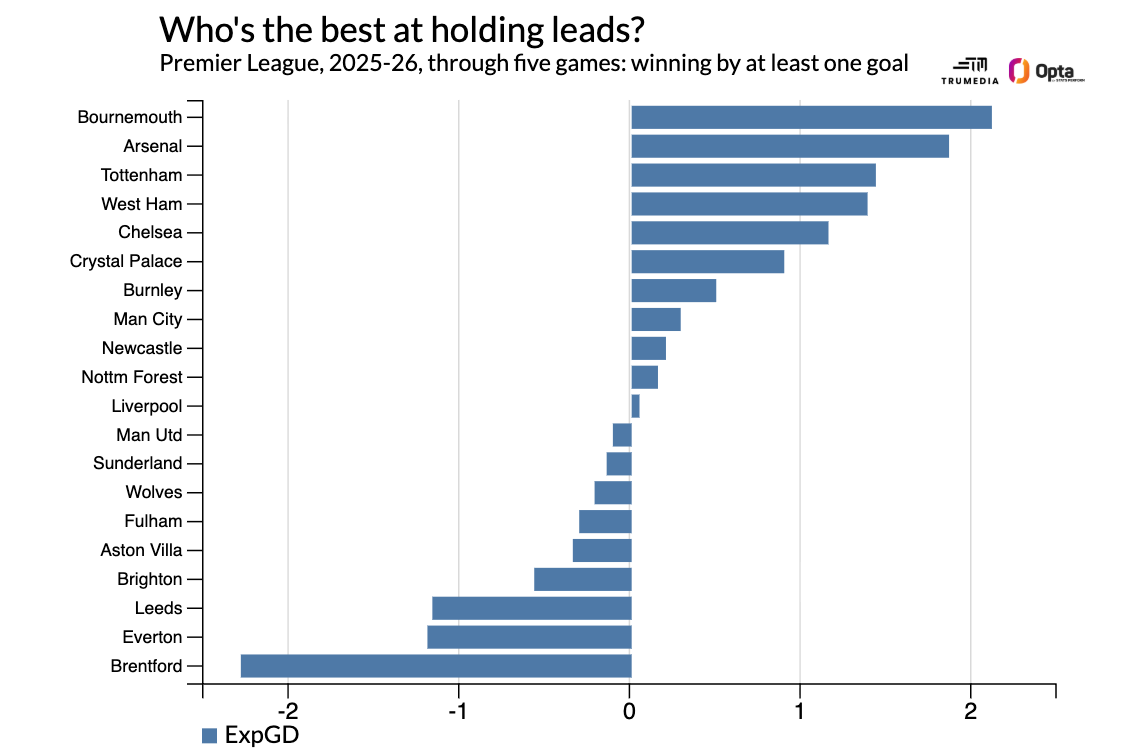

Liverpool have needed so many late winners mainly because they’ve been quite poor whenever they’ve taken the lead. They’ve conceded 25 shots and attempted 25 when they’ve been up by at least a goal.

Now, it’s normal for teams not to register as many attempts once they’re leading, but good teams usually make up for that by creating higher-quality attempts than normal when they do attack because their opponent has to push the action and leave space behind the defense. Liverpool, though, haven’t exploited that.

Liverpool’s xG created and conceded is almost exactly even when they’re winning, and it has led to four goals being scored and five being conceded.

We’re still too early into the season to be too confident about any conclusions, but this sure looks like the profile of a team that has spent a ton of money on attack-first players and has spent most of the season playing with only two true midfielders, neither of whom is defensive-minded.

When opponents aren’t incentivized to attack against Liverpool — when they’re tied and we’re in the second half, a draw is in sight — then the imbalance doesn’t matter. Liverpool keep the ball and their attackers attack, and it all works. But once the other team has to attack, Liverpool can’t control the game anymore. They had 55% of the final-third possession when winning last season; this year, it’s down to 46%.

That’s not too surprising — it might even be by design — but what is surprising is that a team with Florian Wirtz and Mohamed Salah and Dominik Szoboszlai and Hugo Ekitike and Alexander Isak still hasn’t made teams really pay on the counter-attack. Liverpool’s xG per shot when they’re leading is 0.10 — or slightly below the league average for teams that are ahead. Last season, it was up at 0.13.

So what does it all mean?

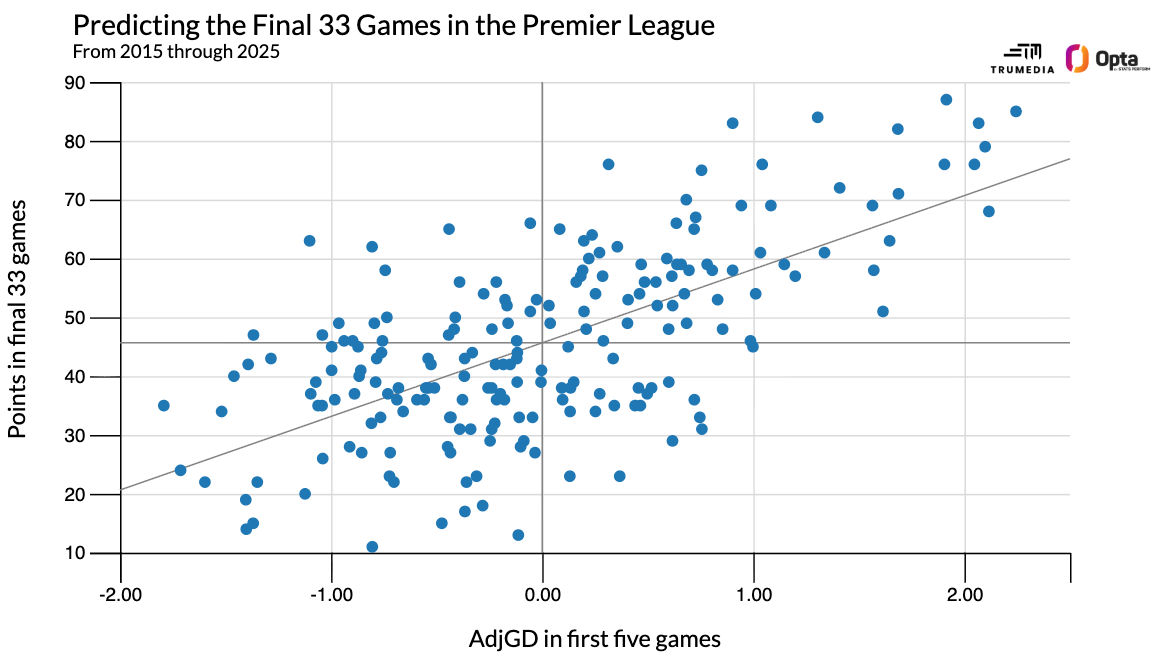

Though Liverpool’s matches have been strangely partitioned this season, it’s better to look at everything together, and history tells us as much. From the previous 10 Premier League seasons, I looked at a number of statistics from Stats Perform for the first five matches to see what best correlated with points won over the final 33 games of the season. Looking at only certain game states made the predictions worse, as did removing what you might think would be the randomness of penalties.

The stat that best correlated with rest-of-season stats was “adjusted goal differential” — the blend of 70% of Stats Perform’s expected goals and 30% actual goals that I’ve referenced countless times before. It was more accurate than just goals, just expected goals, and just points. The correlation (also known as “r-squared”) was 0.44, which means that 44% of the variation between the points every team has won over the final 33 games over the past 10 seasons can be explained by each team’s adjusted goal difference through the first five games.

Here’s how that looks:

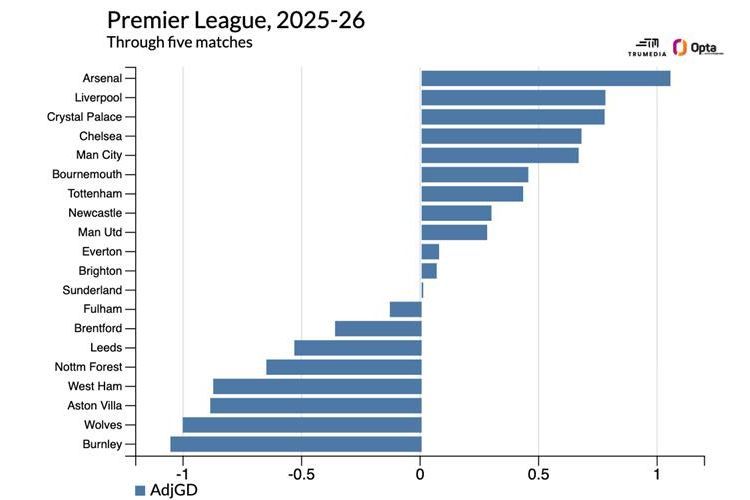

And here’s how things look across the league so far this season, by adjusted goal differential:

Ironically, this is exactly what happened the last time Liverpool won the league in 2019-20. The following season, their adjusted goal differential through the first five games was plus-0.78, the same number they’ve got now. They then won 59 more points over the rest of the season and finished in third.

That team, though, soon lost Virgil van Dijk for the season, followed by their second- and third-choice center backs, Joel Matip and Joe Gomez, respectively. This team has still had its club-record signing, Alexander Isak, on the field for only 24 total Premier League minutes. And though the one match he started also required a last-second winner, at home against Atletico Madrid in the Champions League, it was also the one game where Liverpool dominated after they led. With Liverpool leading, the shot count was close, 12 to 9 in favor of the hosts, but Liverpool created 1.32 expected goals to Atletico’s 0.38.

As it stands, though, Arsenal have played about as well as Liverpool did last season, while Liverpool have played about as well as Arsenal did. Their current adjusted goal differentials are nearly the same as the other team’s full-season marks from last year. Over the past 10 seasons, the best a team has done while playing at Liverpool’s current level — somewhere between a 0.5 and 0.8 adjusted goal differential — was Leicester’s 81 points in their 5,000-to-1 championship season. While the worst a team with a plus-1-or-better adjusted goal differential has done was Liverpool’s 78 points in 2017-18.

Now, it could happen, but the overwhelmingly likely outcome of Liverpool and Arsenal maintaining their current performance levels is that Arsenal wins the league. Given how Bukayo Saka, William Saliba, and Martin Odegaard have already missed significant time and how they’ve already played Liverpool and Manchester City, it seems unlikely that Arsenal decline too much from here on out. So, hang on to their current lead, Liverpool will have to improve; they’ll need to stop falling apart once they take a lead, and they’ll need to start winning some matches before the 85th minute.

But while all those last-second winners can’t be relied upon for the rest of the season, they did happen. Dominik Szoboszlai briefly harnessed the power of gravity against Arsenal, in a way no Arsenal player did against Liverpool. Szoboszlai, too, had the presence of mind to dummy a pass and create a massive opening for Rio Ngumoha to slot home the winner against Newcastle. And because Liverpool have executed in so many of these high-leverage moments already, they’ve built a sizable cushion.

They need to be better from now through the end of the season if they want to win the title, but they don’t actually need to be better than Arsenal. They just need to be four points worse.